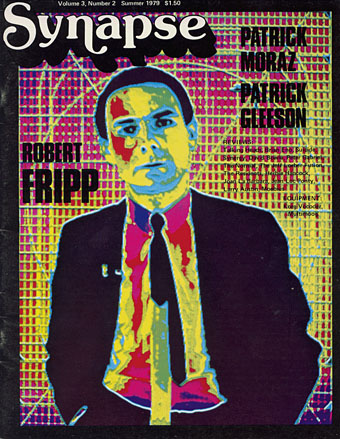

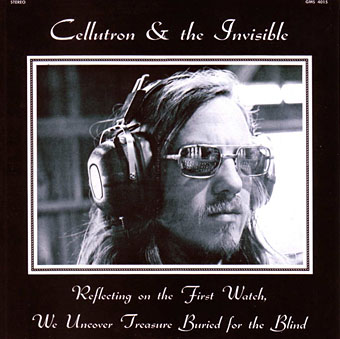

Robert Fripp photographed by Chris Stein. Video posterization by Michael Schiess.

Scans of Synapse, “The electronic music magazine”, are posted here. Issues range from 1976 to 1979, and include interviews with the more notable synthesists of the period, Kraftwerk included. Brian Eno was regularly interviewed by synth mags despite always being reluctant to talk about what equipment he might be using; sure enough he’s featured here. Far more interesting is a longer interview with Robert Fripp that catches the guitarist as he emerged from his self-imposed retirement in the mid-70s with the extraordinary Exposure album. (See a 1979 promo video for that here.) Related: TR-808 drum sequences in poster form by Rob Ricketts.

• More electronic music from the 1970s: “[Don Buchla] showed me that the idea of playing a black-and-white keyboard with one of these instruments was completely ridiculous. It was inappropriate and had nothing to do with the way you would use an electronic instrument.” Suzanne Ciani talks to John Doran about electronic music composition. A collection of her early recordings, Lixiviation, is released by Finders Keepers. Related: The Attack of the Radiophonic Women: How synthesizers cracked music’s glass ceiling.

• “Her writing—full of immigrants, circus animals, freaks, socialists, hipsters, servants, and suffragettes—revels in the atmosphere of the ‘Yellow Nineties,’ a period characterized by Wildean decadence and art for art’s sake.” Jenny Hendrix on Djuna Barnes.

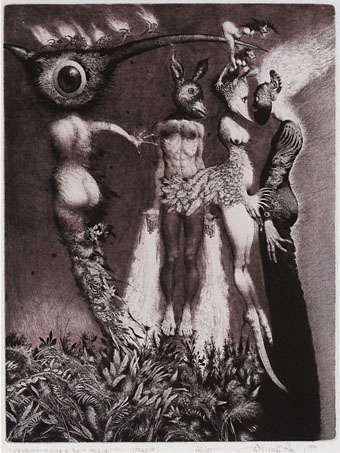

More etchings by Albin Brunovsky at But Does It Float.

• More scanned magazines: the Fuck You Press archive at Reality Studio. A trove of rare publications produced by Ed Sanders in the 1960s with contributions from world-class writers, William Burroughs included.

• “[My parents] were horrified by what I did, but they encouraged me to keep doing it because I was obsessed, and what else could I do?” John Waters writing in (of all places) the Wall Street Journal.

• A time-lapse assembly of Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) by Jeff Desom who explains how he did it here.

• The Occult Experience: a 95-minute documentary on the international occult scene, filmed in 1984–85.

• Compost and Height re-post A Gold Thunder, a song by Julia Holter first sent to them in 2010.

• Drawings by Bette Burgoyne.

• Fade Away And Radiate (1978) by Blondie (featuring Robert Fripp) | Exposure (1978) by Peter Gabriel (produced by and featuring Robert Fripp) | Exposure (1979) by Robert Fripp | Babs And Babs (1980) by Daryl Hall (produced by and featuring Robert Fripp) | Losing True (1982) by The Roches (produced by and featuring Robert Fripp).