Untitled drawing by Sophie Penrose.

• “…many arts producers – much more so than the artists themselves – were over-fearful of the prospect of prosecution, when in nearly all incidents there were no reasonable grounds for bringing charges.” Julia Farrington of Index on Censorship on self-censorship by artists and art institutions in the UK.

• “Tons of tones – some dissolved in beats, some beatless treatments – in a continuous mix of current ambient and electronic goodies, pouring more than a score of ambi-valent shapes and etheric waves into an occluded reverb-trail echo-veil mood-stream.” Ambivalentine, a mix by Albient.

• “I was followed by a bee, a golden bee. For three years, every day, the golden bee followed us.” Forty years ago Penthouse magazine talked to Alejandro Jodorowsky. This month Dazed magazine asked the polymath twenty questions.

• “…investigators were stupefied to find the spymaster’s quarters full of pink leather whips, cosmetics, and pornographic photographs, framed in snakeskin.” Erik Sass on Colonel Redl and a gay spy scandal in the Vienna of 1913.

• “With no one to sponsor him, Marino Auriti’s dream museum became the stuff of legends.” Stefany Anne Golberg on Marino Auriti’s Enciclopedico Palazzo del Mondo.

• The Crime Epics of Louis Feuillade: YouTube links and more. Related: YouTube’s Vault of Horrors.

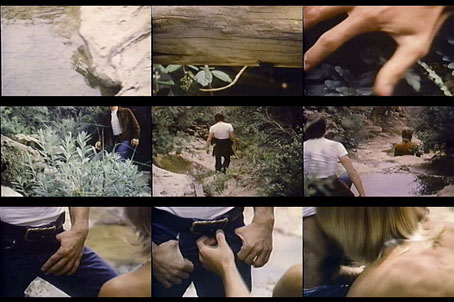

• Werner Herzog: 50 years of potent, inspiring, disturbing films.

• The doors of perception: John Gray on Arthur Machen.

• Some Sort of Alchemy: Albert Mobilio on Sun Ra.

• British Pathé’s film of ghost hunters in 1953.

• “Escape your search engine Filter Bubble”

• RIP Jack Vance

• Bumble Bee Bolero (1957) by Harry Breuer | The L S Bumble Bee (1967) by Peter Cook & Dudley Moore | Ant Man Bee (1969) by Captain Beefheart and His Magic Band | Be A Bee (2009) by Air