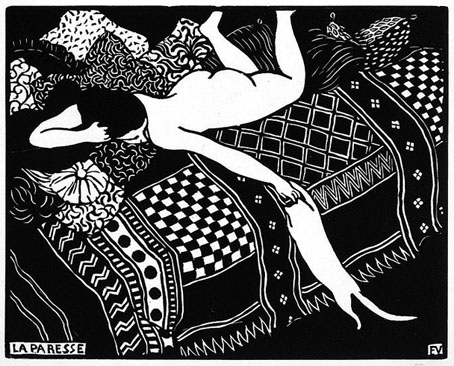

La Paresse (1896).

Félix Vallotton (1865–1925) was a Swiss/French artist often classed among the Symbolists although few of his paintings really suit the label. The closest he comes to Symbolism is in his membership of the Nabis, a small group of artists whose approach to painting was as much concerned with the surface of the picture as with the image that surface represented, something they pursued throughout the 1890s with a revolutionary fervour. Japanese prints were popular among the Nabis, an influence which is evident in Vallotton’s woodcuts although you don’t always seen many of these in Symbolist studies. Vallotton’s paintings are of such a high standard that most of my books favour his canvases over his woodcuts, with the latter appearing, if at all, in the form of the small portraits he made of notable writers. The examples here are from a substantial collection at Wikimedia Commons which include many I haven’t seen before, including the complete set of Intimités (Intimacies), a series which shows encounters between men and women in darkened rooms.

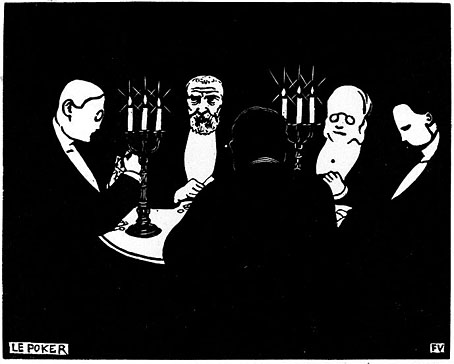

Le Poker (1896).

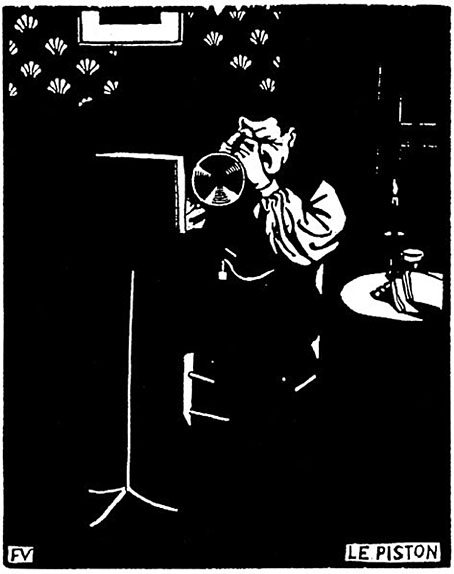

Le Piston (1896).

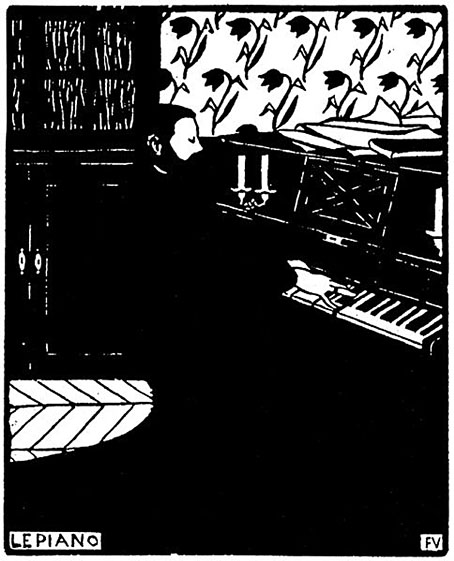

Le Piano (1896).

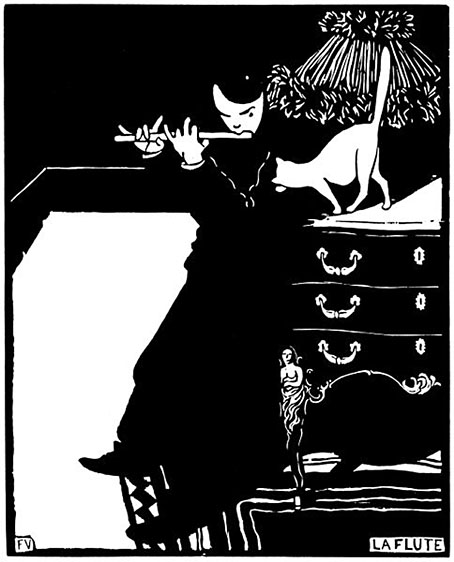

La Flûte (1896).