Still from The Shaman-Girl’s Prayer (1997), a video piece by Mariko Mori. This page has pictures of Mori’s futuristic/cosmic performances, films & environments.

• Time Out of Mind (1979) was a BBC TV series about science fiction writers, five short films concentrating on Arthur C. Clarke, John Brunner, Michael Moorcock, Anne McCaffrey and an sf convention. I was only interested in the Moorcock film at the time, not least because it featured a short clip of Hawkwind playing Silver Machine, and inserted scenes from the film of The Final Programme (1973) between the interviews. The Moorcock episode is less about his books than about New Worlds magazine and the so-called New Wave of sf in general, so you also see rare footage of M. John Harrison in a Barney Bubbles “Blockhead” T-shirt talking then ascending a limestone cliff, and bits of interviews with Brian Aldiss and Thomas Disch. Ballard isn’t interviewed but is present via a scene from the Harley Cokeliss film Crash! (1971) in which Gabrielle Drake slides in and out of a car while someone reads Elements of an Orgasm from The Atrocity Exhibition.

• “…there happened to be a book on Ritual Magick that talked about John Dee and summonings and Dr. Faust and all that kind of stuff. So then obviously at that age, too, I read HP Lovecraft and then Michael Moorcock and what they call fantasy literature. Through HP Lovecraft I discovered Arthur Machen, and I think that sort of percolated down inside…” Dylan Carlson of Earth talking to Steel for Brains. The Wire has the vinyl-only track from the new Earth album, Primitive And Deadly, and a track from Carlson’s solo album, Gold. Related: Artwork by Samantha Muljat, designer/photographer for the new Earth album.

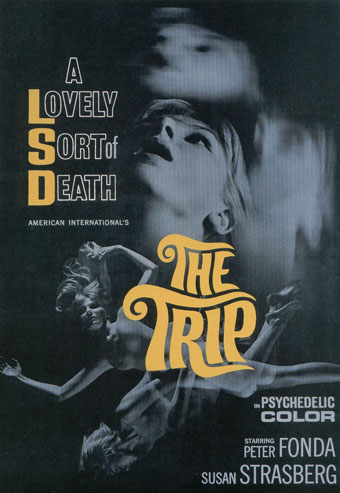

• Phantasmaphile has details of the next two issues of deluxe occult magazine Abraxas. Issue 6 includes a major feature on Leonora Carrington while Luminous Screen is a special issue devoted to occult cinema.

• More Broadcast: Video of a performance at Teatro Comunale di Carpi, March 2010 (part 2 here), and “constellators and artifacts” at A Year In The Country.

• “Petition demands return of ‘Penis Satan’ statue to Vancouver.” There’s an uncensored photo of the contentious statue here.

• Literary Alchemy and Graphic Design: Adrian Shaughnessy on James Joyce’s writings among graphic designers.

• Frank Pizzoli talks to John Rechy about “the gay sensibility”, melding truth and fiction, and his literary legacy.

• Mixes of the week: Secret Thirteen Mix 127 by Roberto Crippa, and FACT Mix 459 by Craig Leon.

• Alan Moore has finished the first draft of his million-word novel, Jerusalem.

• Crazy pavings: Alex Bellos on Craig Kaplan’s parquet deformations.

• Noise Not Music: “Live recordings, obscure cassettes and more…”

• Zoot Kook (1980) by Sandii | Rose Garden (1981) by Akiko Yano | Telstar (1997) by Takako Minekawa