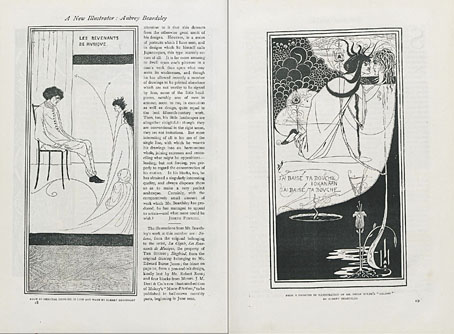

The Call of Cthulhu (1988): in the upper half there’s the big sun from Bob Peak’s poster for Apocalypse Now, in the lower half a radical reworking of Arnold Böcklin’s The Isle of the Dead.

In 1990, shortly after the first season of Twin Peaks had finished showing in the US, Video Watchdog magazine ran a feature by Tim Lucas which attempted to trace all the various cultural allusions in the character names and dialogue: references to old TV shows, song lyrics and the like. This was done in a spirit of celebration with Lucas and other contributors welcoming the opportunity to dig deeper into something they’d already enjoyed. This week we’ve had a similar unravelling of textual borrowings in a TV series, only now we have the internet which, with its boundless appetite for accusing and shaming, can often seem like something from the grand old days of the Cultural Revolution.

The Call of Cthulhu (1988): a more subtle allusion to Apocalypse Now.

The latest culprit ushered to the front of the assembly for the Great Internet Struggle Session is Nic Pizzolatto whose script for True Detective has indeed been celebrated for its nods to Robert Chambers and The King in Yellow. It’s also in the process of being condemned for having borrowed phrases or aphorisms from Thomas Ligotti’s The Conspiracy Against the Human Race (2011). See this post for chapter and verse.

The Call of Cthulhu (1988): It’s not very clear but that’s a boat from The Creature from the Black Lagoon.

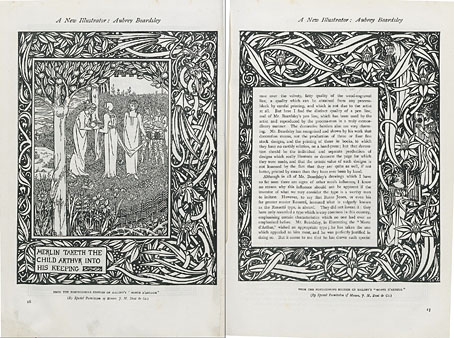

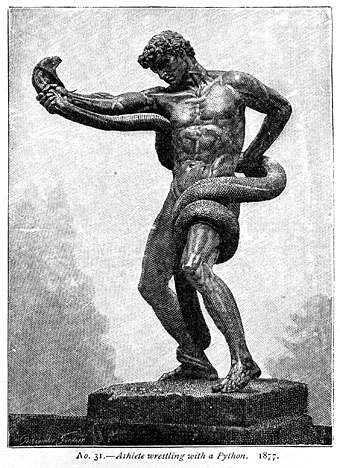

If I find it difficult to get worked up over all this pearl-clutching it’s because a) it shows a misunderstanding of art and the way many artists work, b) True Detective was an outstanding series, and I’d love to see more from Pizzolatto and co, and c) I’ve done more than enough borrowing of my own in a variety of media, as these samples from my adaptation of The Call of Cthulhu demonstrate, a 33-page comic strip where there’s a reference to a painting, artist or film on almost all the pages, sometimes several on the same page.

The Call of Cthulhu (1988): Ophelia by Millais.

Cthulhu is a good choice here since Pizzolatto’s story edged towards Lovecraft via the repeated “Carcosa” references. You’d think a Lovecraft zine of all things would know better than to haul someone over the coals for borrowing from another writer when Lovecraft himself borrowed from Robert Chambers (and Arthur Machen and others), while “Carcosa” isn’t even original to Chambers’ The King in Yellow but a borrowing from an Ambrose Bierce story, An Inhabitant of Carcosa (1886). Furthermore, Lovecraft famously complained about his own tendencies to pastiche other writers in a 1929 letter to Elizabeth Toldridge: “There are my ‘Poe’ pieces and my ‘Dunsany pieces’—but alas—where are any Lovecraft pieces?”