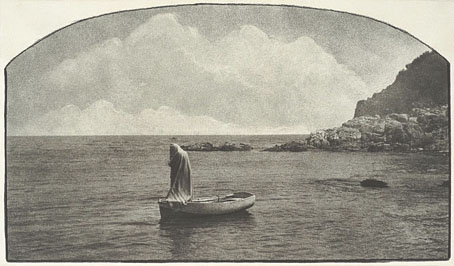

La Hora del Fantasma (no date) by Joaquim Pla Janini.

• Many of the art links featured here are tips from Thom Ayres, so it’s only right to point to his new album project which he’s funding through Kickstarter and embellishing with his own nature photography.

• Anne Billson is another writer beguiled by Philippe Jullian’s masterwork, Dreamers of Decadence. And thanks to Ms Billson for drawing attention to the insane opening of Crime Without Passion (1934).

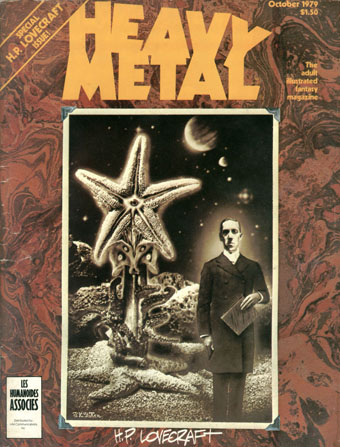

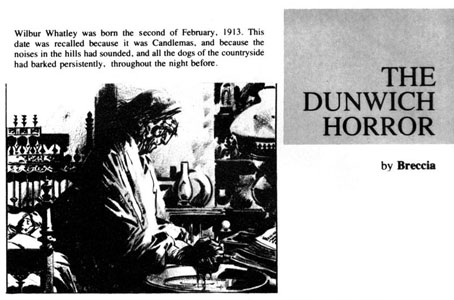

• Does this fake ad for The Necronomicon use one of my Cthulhu pictures? Possibly. Get the picture for yourself in this year’s Cthulhu calendar. (My thanks to everyone who’s bought a copy so far.)

To break the ice, I talk about books: he is delighted to discover that I have read his beloved Denton Welch, also J. W. Dunne’s An Experiment With Time. I have found them in my old school library, and know both have been a tremendous influence on him in different ways. Knowing of his interest I also mention that I have just read Colin Wilson’s The Quest For Wilhelm Reich, published the year before. He likes Wilson, he says, jokes that “the Colonel” with his cottage in Wales in Wilson’s Return of the Lloigor and his own Colonel Sutton-Smith from The Discipline of DE are one and the same. On something of a roll, I mention Real Magic by Isaac Bonewits, and he acknowledges that it has “some good information” – but is much more enthusiastic about Magic: An Occult Primer by David Conway [years later I would discover that Burroughs & Conway had in fact exchanged letters on various subjects pertaining to magic, occultism, and psychic phenomena – but that is decidedly another story!]

Matthew Levi Stevens recalls The Final Academy and an encounter with William Burroughs thirty years ago.

• Locomotif: A short survey of trains, music & experiments: Gautam Pemmaraju on Kraftwerk, Pierre Schaeffer, Luigi Russolo and others.

• A flip-through of The Graphic Canon, volume 2. Wait to the end and you’ll see a couple of my Dorian Gray pages. Imprint has a review of the book.

• Julian Bell reviews two new books about Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich.

• Alan Moore talks to The Occupied Times about art, education and anarchism.

• Colin Dickey reviews Vilém Flusser’s Vampyroteuthis Infernalis: A Treatise.

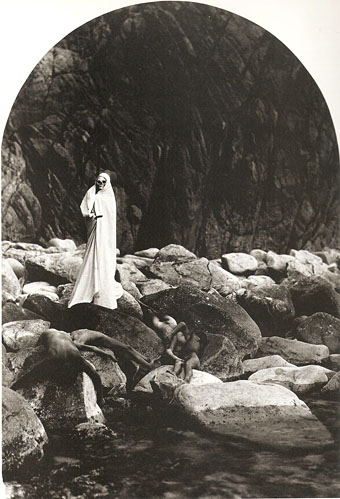

Las Parcas II (1930) by Joaquim Pla Janini.

• Michael Newton reviews A Natural History of Ghosts by Roger Clarke.

• Golden Age Comic Book Stories revisits the work of Sidney Sime.

• Front Free Endpaper asks “What’s in an inscription…?”

• Ghosts (1981) by Japan | Ghosts (2008) by Ladytron | Ghosts (2012) by Monolake.