Stonehenge Suite, No.10 (1977) by Malcolm Dakin.

• “Part of me always wanted to write a teatime drama. That’s something that I wanted to get out of my system,” says director Peter Strickland. The results may be heard here. In the same interview there’s news that Strickland will be adapting Nigel Kneale’s The Stone Tape for radio later this year.

• “He was, as one obituary stated in terms unusually blunt for the time, ‘not as other men’.” Strange Flowers on the eccentric and profligate Henry Cyril Paget (1875–1905) aka The Dancing Marquess.

• “Please tell Mr Jagger I am not Maurits to him.” MC Escher rebuking The Rolling Stones. The artist is the subject of a major exhibition at the National Galleries of Scotland from June 27th.

Often mentioned in the same breath as works of James Joyce and Samuel Beckett, Ó Cadhain’s novel is, in some ways, even more radically experimental. For starters, all the characters are dead and speaking from inside their coffins, which are interred in a graveyard in Connemara, on Ireland’s west coast. The novel has no physical action or plot, but rather some 300 pages of cascading dialogue without narration, description, stage direction, or any indication of who’s speaking when.

Niamh Ní Mhaoileoin on the newly-translated Cré na Cille (The Dirty Dust) by Máirtín Ó Cadhain

• Paul Woods examines “10 Edgy Properties No Film Producer Dared To Touch

(Yet)”. No. 2 is David Britton’s Lord Horror.

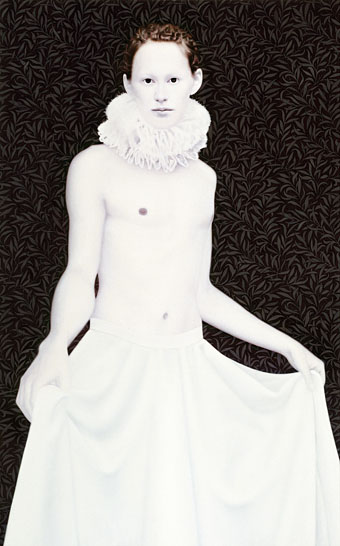

• Mallory Ortberg ranks paintings of Saint Sebastian “in ascending order of sexiness and descending order of actual martyring”.

• The Sign of Satan (1964): Christopher Lee in a story by Robert Bloch for The Alfred Hitchcock Hour.

• Sympathy For The Devil – The True Story of The Process Church of the Final Judgment.

• At Dangerous Minds: Paul Gallagher on the seedy malevolence of Get Carter (1971).

• Mix of the week: Sonic Attack Special – Earth by Bob’s Podcasts.

• Sanctuary Stone (1973) by Midwinter | The Litanies Of Satan (1982) by Diamanda Galás | Sola Stone (2006) by Boris