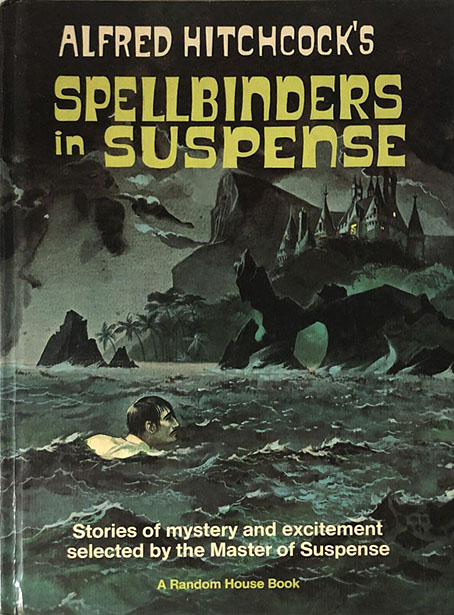

Cover art by Harold Isen, 1967.

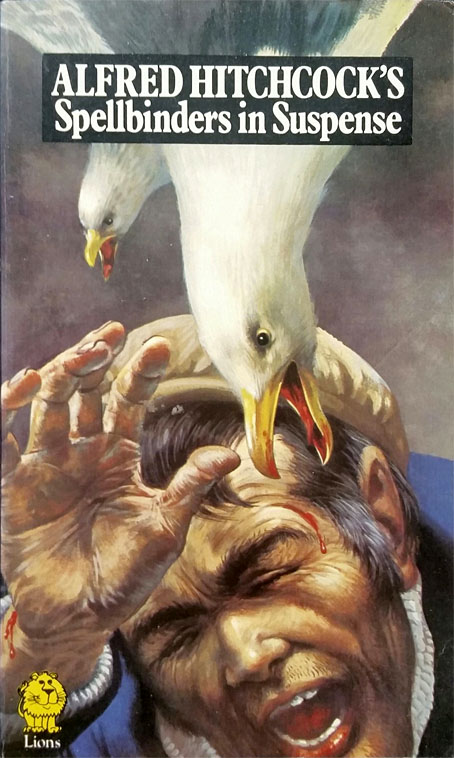

I watched Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds again recently, after which I went looking for the contents list of the collection where I first read Daphne du Maurier’s story. The book in question, Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbinders in Suspense, is one of the many anthologies that used the director’s name to lure potential purchasers, even though Hitchcock didn’t choose any of the stories and didn’t write any of the introductory notes or mini essays that these volumes usually contain. Spellbinders in Suspense was first published in 1967, and is one of the few such collections to feature a story that relates to one of Hitchcock’s films, so it’s odd that Random House chose to depict a scene from Richard Connell’s The Most Dangerous Game on the cover. The copy that I owned was a Fontana Lions paperback from 1974 which rectified this with a cover that certainly stimulated my interest; growing up in a seaside town I didn’t need much convincing about the viciousness of the common seagull. The book has two further Hitchcock connections via Roald Dahl’s The Man from the South, which had been dramatised in 1960 for the Alfred Hitchcock Presents TV series, and Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper, a story by Psycho author Robert Bloch that first appeared in Weird Tales and which turns up in many anthologies.

Cover artist unknown, 1974.

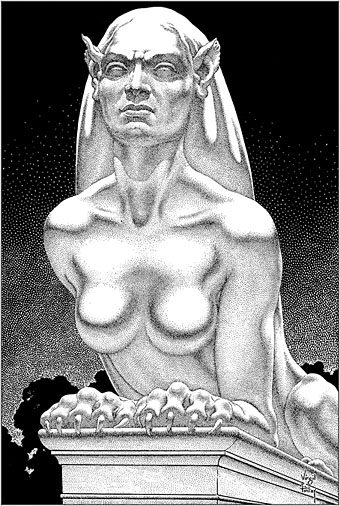

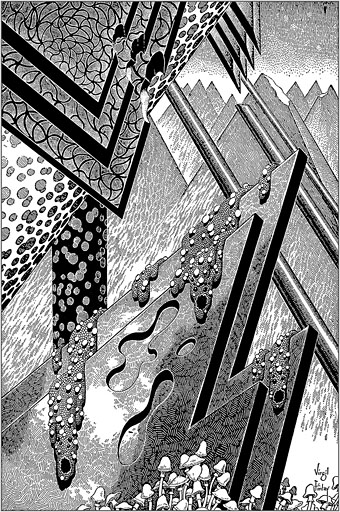

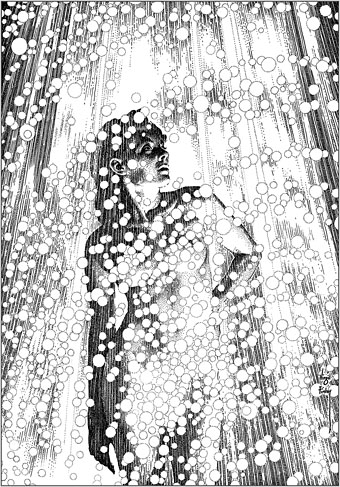

I don’t know when I first saw The Birds but it must have preceded my reading of the book since I remember being surprised at how different du Maurier’s story was to the film. Hitchcock and screenwriter Evan Hunter kept the basic idea of inexplicable bird attacks but moved the location from Cornwall to northern California, retaining a single incident in the scene where a dead seagull is found on a doorstep. The page for Spellbinders in Suspense at the Hitchcock Zone—an excellent information resource—has some of the illustrations by Harold Isen that appeared in the hardback edition, including a drawing of yet more marauding seagulls.

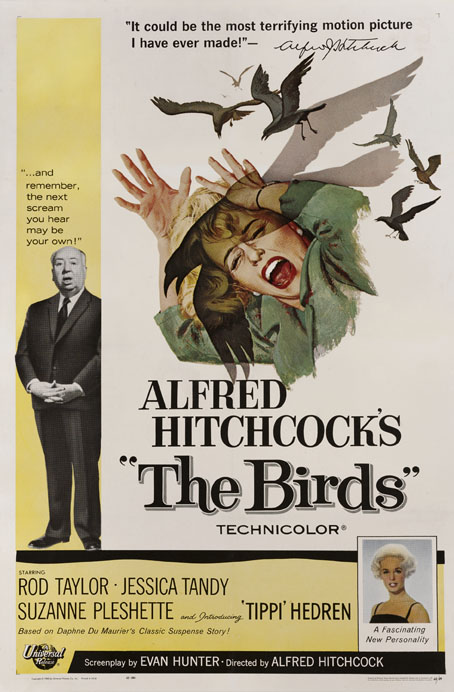

If you want an idea of Hitchcock’s personal popularity and the power of the Hitchcock brand, look no further than the US poster for The Birds in which the director’s name is almost as large as the title (and much more prominent than those of the actors), while the man himself is also there to offer further enticement. Hitchcock was the first film director I became aware of by name, although when I was 10 or 11 I doubt I could have told you what it was that a film director actually did. The ubiquity of the Hitchcock brand made his presence unavoidable in the 1950s, 60s and 70s in a manner more usually reserved for film stars and pop stars; in addition to books, radio shows and the TV series there was Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, which launched in 1956 and was still running 50 years later; also a long-playing record, Music To Be Murdered By, in which the director’s familiar drawl delivers snatches of black humour between each musical selection. In the book department, the Hitchcock Zone lists 127 Hitchcock-themed anthologies, many of which (like Spellbinders in Suspense) received multiple reprints. And those 127 volumes are just the collections. There’s also Robert Arthur’s mystery novels for younger readers, Alfred Hitchcock and the Three Investigators (1964–87), a 43-volume series in which a trio of Californian boys undertake investigations—many of them with a spooky flavour—whose outcome they report to Mr Hitchcock at the end of each story. I read the first few books in the series, also another story collection compiled by Robert Arthur, Alfred Hitchcock’s Ghostly Gallery (1962), a book which in its Puffin reprint gave me my first encounter with The Upper Berth, F. Marion Crawford’s frequently anthologised tale of clammy nautical horror. Ghostly Gallery was another illustrated collection, with scratchy drawings by Barry Wilkinson.

Cover art by Barry Wilkinson. The Puffin edition dates from 1967 but this edition has a decimal price which places it circa 1971.

The extension of the Hitchcock brand into books aimed at children is a curious thing when none of his films are intended for a young audience. My edition of Spellbinders in Suspense was published by a juvenile imprint yet all the stories are ostensibly adult fare. Children in Hitchcock’s cinema are either treated as a nuisance (the small boy who has his balloon burst by Bruno in Strangers on a Train) or end up in serious peril, as they do in The Birds, The Man Who Knew Too Much (kidnapped and threatened with murder), Strangers on a Train (an out-of-control merry-go-around), and, notoriously, in Sabotage, where another small boy is made to unwittingly carry a time-bomb that blows him and a busload of passengers to pieces. Strangers on a Train also reinforces the Hitchcock brand by showing Farley Granger’s character with one of the earliest anthologies, Alfred Hitchcock’s Fireside Book of Suspense Stories, in the scenes on the train at the beginning of the film.

Product placement: Robert Walker and Farley Granger in Strangers on a Train (1951).

All of this retrospection has had me wondering whether Hitchcock might have been interested in adapting another Daphne du Maurier story, Don’t Look Now, since The Birds was his second adaptation after Rebecca. Supernatural stories turn up in the Hitchcock TV series, and there are several more anthologies like Ghostly Gallery yet the films mostly avoid the paranormal (although Vertigo toys with the idea for its first half hour or so). Nevertheless, the subject is given ambivalent treatment in du Maurier’s story which has other qualities that might have appealed. The story wasn’t published until late 1970, however, by which time Hitchcock was planning his return to London with Frenzy. And besides which, the film we have is more than adequate, as well as being a much more faithful adaptation than Melanie Daniels’ journey into avian nightmare.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Painted devils

• The poster art of Josef Vyletal

• The Magic Shop by HG Wells