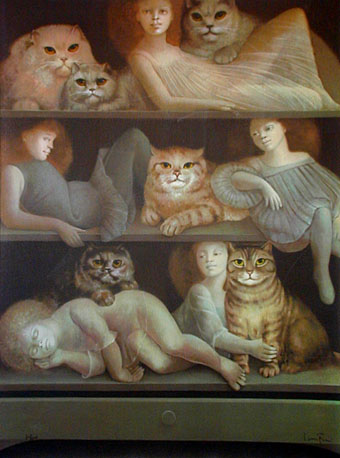

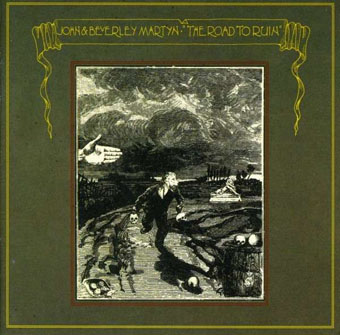

The Road To Ruin (1970) by John & Beverley Martyn. Art: Un Semaine de Bonté (1934).

Having already looked at cover art featuring the work of Salvador Dalí and René Magritte, a similar post for Max Ernst seemed inevitable. I did search for Ernst cover art after the Dalí post but at the time there were fewer examples. As usual there may be more than these since Discogs is the main search tool and they (or the albums) don’t always credit the artists. Despite having several books of Ernst’s work I’ve not been able to identify all the artwork so the Ernst-heads out there are welcome to fill in the gaps.

The Road To Ruin was John Martyn’s fourth album, and the second he recorded with wife Beverley. I’m surprised that this is the earliest example, I’d have expected a classical album or two to have predated it.

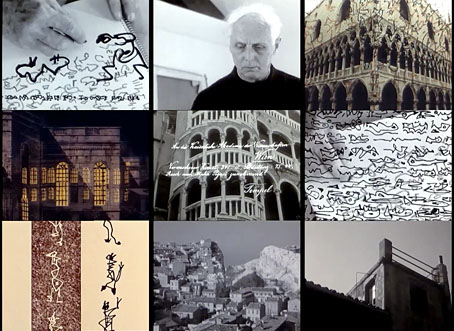

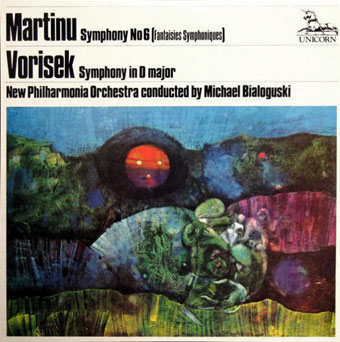

Martinu’s Symphony No. 6 (Fantaisies Symphoniques) / Vorisek’s Symphony In D Major (1971); New Philharmonia Orchestra, Michael Bialoguski. Art: Bottled Moon (1955).

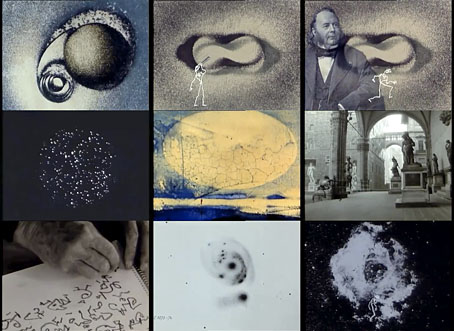

Bluebeard’s Castle by Béla Bartók (1976); Tatiana Troyanos, Siegmund Nimsgern, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Pierre Boulez. Art: The Eye of Silence (1943–44).

Bluebeard’s Castle is my favourite opera, and The Eye of Silence is my favourite Ernst painting, so this is a dream conjunction even if the match doesn’t work as well as it did for the cover of The Crystal World by JG Ballard. One to seek out.