Can Carnacki make any claim to be taken seriously as a detective? If he solves anything it is by force of will, rather than the application of deductive powers. He is no Sherlockian ironist, no high-domed mental traveller. He stands as close to Holmes as Mike Hammer does to Philip Marlowe. His methods are enthusiastic but basic: good old-fashioned head-in-the-door stuff. He is not so much a “ghostbuster” as a self-starting lightning rod for psychic phenomena that has not yet been housebroken.

Thus Iain Sinclair in a typically acerbic afterword to the 1991 Grafton paperback of Carnacki, the Ghost-Finder by William Hope Hodgson. Holmes would indeed look askance at Carnacki’s methods but that didn’t prevent the occult investigator being drafted as one of The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes in the first television series of that name in 1971. I was reminded of this dramatisation following last week’s discussion of Hodgsonian cinema; I’ve known about the episode for years—notable for having Donald Pleasence in the role of Thomas Carnacki—but hadn’t watched it until this week courtesy of YouTube.

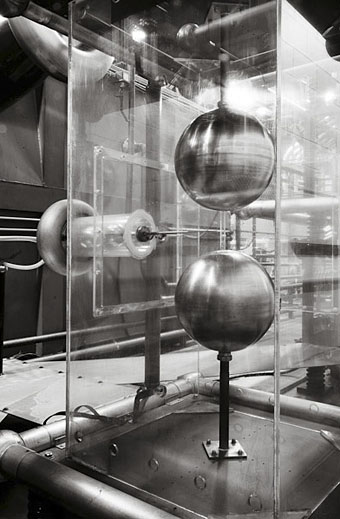

Philip Mackie wrote the script for The Horse of the Invisible, and Alan Cooke was the director. Their adaptation is interesting mostly for seeing a Hodgson story dramatised; as a piece of television the presentation is serious and well-acted but looks rather creaky today, suffering from the over-lit artificiality that always blighted studio-shot productions attempting to create any kind of atmosphere. Donald Pleasence is his typical lugubrious self which doesn’t really suit Carnacki’s bull-headed enthusiasm but I don’t mind that, Pleasence was a good actor so it’s a treat to see him play the part. And we do get to see Carnacki’s “electric pentacle” in action (Carnacki enjoys his Edwardian gadgets) in the midst of which the beleaguered Michele Dotrice is forced to spend the night. The most successful Carnacki stories are those that play to Hodgson’s strengths as a writer of supernatural dread, stories such as The Gateway of the Monster or The Hog. The Horse of the Invisible doesn’t attain the heights of those tales but then it would be a doomed venture trying to conjure Hodgson’s cosmic horrors on a limited budget. With this story you get a taste of the supernatural, which no doubt sets it apart from the other “Rivals”, whilst staying within the bounds of credibility.

There’s one curious detail worth mentioning: in both the story and the dramatisation the character of the fiancé is named “Charles Beaumont”. There was a real Charles Beaumont, a screenwriter responsible for many scripts for The Twilight Zone TV series, as well as for some of the superior American horror films of the 1960s, including Night of the Eagle, The Haunted Palace (Roger Corman’s adaptation of The Case of Charles Dexter Ward) and The Masque of the Red Death. In last week’s discussion I mentioned John Carpenter’s The Fog as a good example of Hodgsonian cinema on account of its ghost pirates. My memory may be playing tricks but I’m sure that Carpenter has a reference to a “Charlie Beaumont” in either The Fog or Halloween, both films being littered with significant character names. (There’s a “Mr Machen” in The Fog). Donald Pleasence was in Halloween, of course, playing a doctor with a name lifted from Psycho. I’ve searched in vain for the Beaumont reference; does this ring a bell for any Carpenter-philes?

Both series of The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes are available from Network DVD.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Tentacles #2: The Lost Continent

• Tentacles #1: The Boats of the ‘Glen Carrig’

• Hodgson versus Houdini

• Weekend links: Hodgson edition

• “The game is afoot!”

• Druillet meets Hodgson