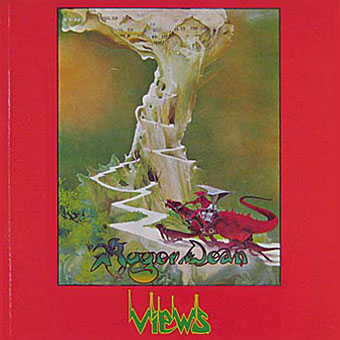

Kieran at Sci-Fi-O-Rama was in touch recently asking me to contribute a paragraph about a favourite Roger Dean picture for this feature about the artist. The following splurge of polemic was the result, something I’d been intending to write for a while. Since so many words would have overwhelmed the other contributions it’s being presented here while Kieran’s post has a variety of shorter appreciations and further examples of Dean’s art and design.

Pathways (1973). A slightly reworked version of the original painting.

“Science fiction is unfortunate in having a most unsatisfactory framework of existence—it’s considered literary kitsch. I believe it should be the mainstream of literature because all the books that have become important down the generations of civilisation have been books about ideas. Superficially, science fiction would seem to offer the most scope for idea content, but the promise is unfulfilled. Good ideas and good writing rarely coincide. All too often the medium is used for entertainment alone and its potential beyond this should be obvious to everyone. I don’t just mean in the sense of fantasy technology. The potential for anticipating human evolution is there and perhaps the means to bring it about and definitely the means to bring about a social evolution.”

Roger Dean, interviewed in Visions of the Future (1976).

If popularity is often a curse as well as a blessing, it’s been Roger Dean‘s curse to see his work dismissed along with many other products of a decade—the 1970s—with more than its share of cultural heroes and villains. Music journalists in Britain have for years given the impression that the arrival of the Sex Pistols in 1976 swept away all that preceded them, in particular bands such as Yes whose album covers had helped raise the visibility of Dean’s art to an international level. This is not only a lazy assumption, it’s also wrong. When Yes released Going For the One in 1977 it was their first studio album in three years, yet despite the punk explosion it went to no. 1 in the UK album charts, while a rare single release from the band made the UK top ten. Yes were playing sell-out tours in Europe and the US in 1977 and 78, as were Pink Floyd whose The Wall was massively popular worldwide in 1979. Punk didn’t sweep prog away, what happened with its advent was that progressive rock and everything associated with it—Roger Dean’s art included—became critically disreputable almost overnight, such that no music journalist would dare say anything good about it. That disrepute has persisted for thirty years despite a lasting and indelible influence. This is an old argument but some facts often need restating anew. *

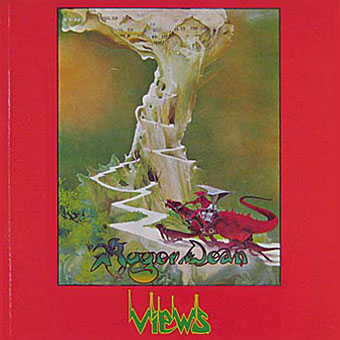

Views (1975).

I was 13 in September 1975 when Roger Dean’s first collection of his illustration and design work, Views, was published. At that time, I hadn’t heard any of the music to which his paintings and drawings were attached, and I didn’t even see a copy of the book until February 1976 when I happened to be in London on a school trip and found a big pile of what I guess was the second edition in Foyle’s book shop. This appeared at exactly the right moment. I wasn’t listening to the music but I was reading a lot of science fiction, and was starting to notice and imitate the work of various paperback artists. I recognised many of the pictures in Views from the covers displayed in the window of our local record shop, Cobweb, whose shopping-bag logo was a cowled magician figure à la Dean or Rodney Matthews. It’s difficult to say what struck me about Dean’s work at the time since you rarely articulate your preferences at that age. I think I liked the consistency of vision and the invention which blended the organic and mechanical, the architecture which looked at once ancient and futuristic, and the flat landscapes which put lone pine trees into rocky terrain familiar from Japanese and Chinese prints. For a teenager his style was also relatively easy to imitate if you forgot about basic things such as imagination and finesse, and I spent a year producing a lot of badly-drawn reptiles posed against lurid watercolour skies.

Continue reading “Roger Dean: artist and designer”