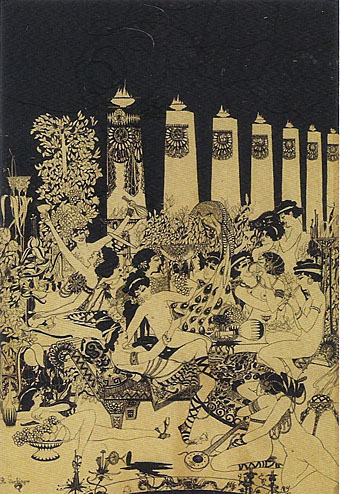

Bacchanal by René Gockinga.

A guest post today by Sander Bink who generously translated his latest piece of research into the Dutch artists of the early 20th century who took the Beardsley style as a foundation for their own black-and-white delineations. As with this earlier post on the subject, many of these drawings are very good but the artists are less well-known than the Beardsley followers in other countries who were their contemporaries. Here’s Sander.

* * *

Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to another episode of ‘Droomkunst’. This time we’ll discuss our cult hero Joseph René Gockinga who has a drawing exhibited at the Singer Museum Droomkunst exhibition. An obvious choice, because how often do you see his work—which I wrote about more in detail here—in a museum? Almost never. In 1976, two works by Gockinga were shown in the Kunstenaren der Idee exhibition but unfortunately I was only just born that year. The current locations of these works by the way is still unknown to me.

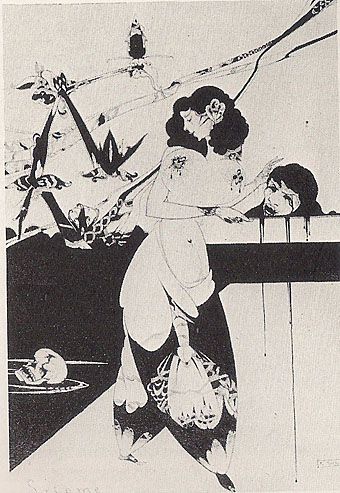

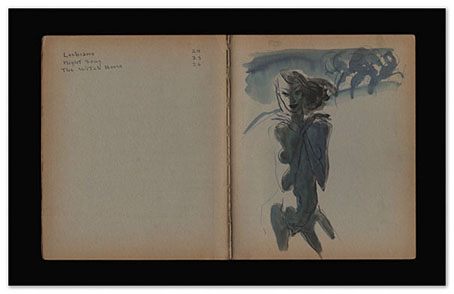

Salomé by René Gockinga.

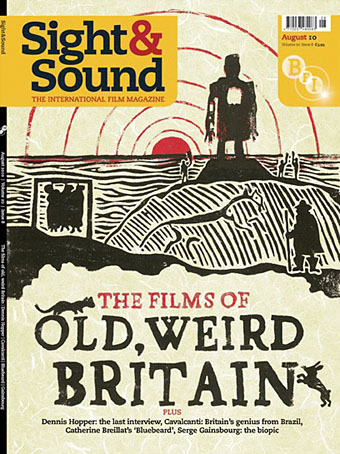

One of them, however, Gockinga’s version of Salomé, resurfaced in 1995 but I don’t know the current location either. And the acclaimed Louis Couperus Museum last year showed an unknown Couperus illustration of Gockinga from a private collection (no, not mine). In Droomkunst now hangs a small but fine work in a similar style: the Bacchanal already mentioned here. The Droomkunst catalogue dates the work about 1915. I would dare to date is somewhat earlier, I think 1913.

In his opening speech Singer director de Lorm compared Gockinga’s Bacchanal with the work of Erwin Olaf because of the hedonistic, decadent parallels between the two works. If I remember correctly, de Lorm also talked about certain places preferred by these artists, in addition to the perverse, decadent, decayed Amsterdam also Indonesia and especially Java, which was known as a kind of international gay colony.

Now, our Gockinga has also dwelled there; I do not know exactly where and when, but—and this is information that surfaced after my earlier mentioned article was published—he lived in the late thirties in Bali for a while in the home of the renowned painter W.G. Hofker. And in a recent study Imagining Gay Paradise: Bali, Bangkok, Singapore and cyber-Singapore we read that Gockinga was one of the victims of a scandal; he was arrested because of his homosexuality in December 1938 in Denpasar. Here, the comparison with the 2000 generation of artists limp, which, after all, in Amsterdam and elsewhere were partying without having fears of being arrested for lewd behaviour.

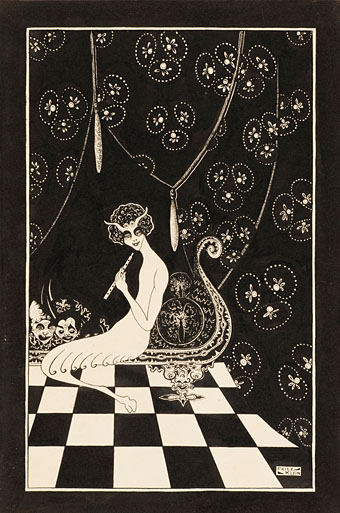

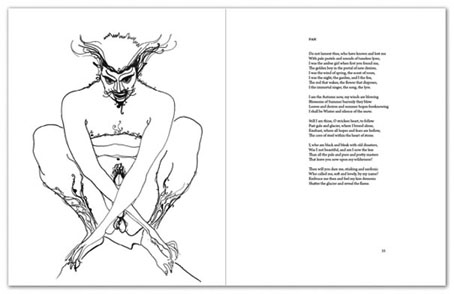

Fritz Klein by René Gockinga.

Where several generations of artists do come together is in the following, in our humble opinion a very nice item that was sent us last year. The majority of Gockinga’s Beardsley and the Nérée-like drawings from around 1917 are still unfortunately lost. Probably the “immoral” nature of his work is the main reason. So the item presented here is, as far as we know for the first time, is a new discovery.

It is a Beardsley-like portrait from 1917 or thereafter and it portrays none other than the painter Fred (Fritz) Klein (1898–1990), father of the famous and important Yves Klein.

Huh? What? How can that be? Well, that is of course very well possible. They were more or less contemporaries (Klein was born in 1898, Gockinga in 1893), were both born in the Dutch East Indies and were back in The Netherlands in 1913. They shared a great interest in art. In 1920, Klein moved to France, where he would make his sunny canvases that he became known for. Before that, he was apparently also in The Hague, where he visited his friend Gockinga. That friend has now made a special and somewhat decadent portrait of Klein: a kind of mythological half-man, surrounded by masks and, as I said, in a nice Beardsley-style. You could interpret the masks and the mix of male/female characteristics in a certain way but I leave that to the viewer. In any case, a special drawing can be added to the mysterious oeuvre of the Dutch Symbolist. Big thanks to the Klein relatives that allowed me to write about and portray it, of course.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Antony Little’s echoes of Aubrey

• Aubrey in LIFE

• Beardsley reviewed

• Aubrey Beardsley in The Studio

• Ads for The Yellow Book

• Beardsley and His Work

• Further echoes of Aubrey

• A Wilde Night

• Echoes of Aubrey

• After Beardsley by Chris James

• Illustrating Poe #1: Aubrey Beardsley

• Beardsley’s Rape of the Lock

• The Savoy magazine

• Beardsley at the V&A

• Merely fanciful or grotesque

• Aubrey Beardsley’s musical afterlife

• Aubrey by John Selwyn Gilbert

• “Weirdsley Daubery”: Beardsley and Punch

• Alla Nazimova’s Salomé