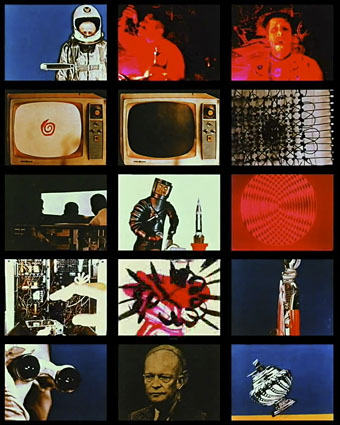

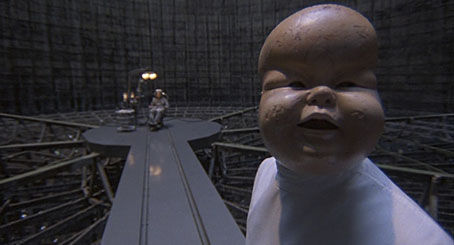

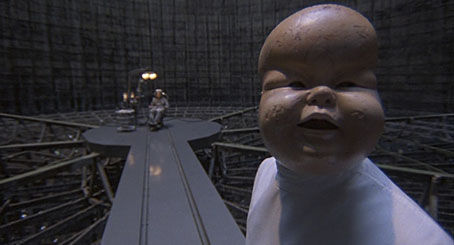

Kafka (1991).

This week I completed the interior design for a new anthology from Tachyon, Kafkaesque, edited by John Kessel and James Patrick Kelly. It’s a collection of short stories either inspired by Franz Kafka, or with a Kafka-like atmosphere, and features a high calibre of contributions from writers including JG Ballard, Jorge Luis Borges, Carol Emshwiller, Jeffrey Ford, Jonathan Lethem and Philip Roth, and also the comic strip adaptation of The Hunger Artist by Robert Crumb. When I knew this was incoming I rewatched a few favourite Kafka-inspired film and TV works, and belatedly realised I have something of a predilection for these things. What follows is a list of some favourites from the Kafkaesque dramas I’ve seen to date. IMDB lists 72 titles crediting Kafka as the original writer so there’s still a lot more to see.

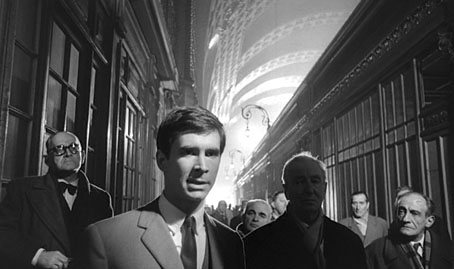

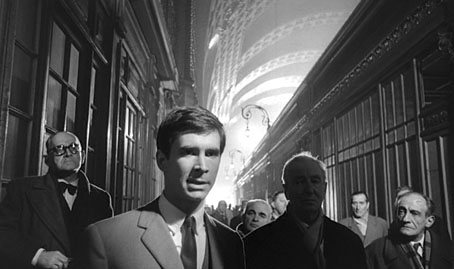

The Trial (1962), dir: Orson Welles.

Orson Welles in one of his Peter Bogdanovich interviews describes how producer Alexander Salkind gave him a list of literary classics to which he owned the rights and asked him to pick one. Given a choice of Kafka titles Welles says he would have chosen The Castle but The Trial was the only one on the list so it’s this which became the first major adaptation of a Kafka novel. Welles always took some liberties with adaptations—even Shakespeare wasn’t sacred—and he does so here. I’m not really concerned whether this is completely faithful to the book, however, it’s a first-class work of cinema which shows Welles’ genius for improvisation in the use of the semi-derelict Gare d’Orsay in Paris as the main setting. (Welles had commissioned set designs but the money to pay for those disappeared at the last minute.) As well as scenes in Paris the film mixes other scenes shot in Rome and Zagreb, with Anthony Perkins’ Josef K frequently jumping across Europe in a single cut. The resulting blend of 19th-century architecture, industrial ruin and Modernist offices which Welles called “Jules Verne modernism” continues to be a big inspiration when I’m thinking about invented cities. Kafka has been fortunate in having many great actors drawn to his work. Here with Perkins there’s Welles himself as the booming and hilarious Advocate, together with Jeanne Moreau, Romy Schneider and Akim Tamiroff.

Brazil (1985), dir: Terry Gilliam.

Having watched Brazil again recently I was struck by how much it resembles the popular view of Kafka’s worlds rather than the Orwellian nightmare which Terry Gilliam first intended. The story is powered by a bureaucratic error caused by a crushed insect, after all, and Gilliam follows Welles in mashing up the styles and motifs of an authoritarian century to create a hybrid world he described as being “on the Belfast/Los Angeles border”. Tom Stoppard had a hand in the screenplay, and there’s another great cast with Jonathan Pryce, Katherine Helmond and Ian Holm. Also a nod to an Orson Welles role with the character named Harvey Lime.

The Insurance Man: Daniel Day-Lewis, Robert Hines & Jim Broadbent.

The Insurance Man (1986), dir: Richard Eyre.

Jim Broadbent played a plastic surgeon in Brazil; here he’s a clerk in the offices of the Worker’s Accident Insurance Institute in Prague. Writer Alan Bennett was preoccupied with Kafka in the mid-1980s: his stage play, Kafka’s Dick (the title does indeed refer to the writer’s penis), was staged the same year as this TV film directed by Richard Eyre, a 70-minute drama which sees a young factory worker trying to find a cure for an industrial illness at the Insurance Institute where one “Doctor Kafka” is employed. Needless to say, his quest for health and some measure of justice becomes Kafkaesque. Kafka here is portrayed by Daniel Day-Lewis in a typically enthralling performance which is never mannered but makes him seem a stranger creature (and a more sympathetic clerk) than his fellow workers. Most of this was filmed in Liverpool in some wonderful old office buildings using a sombre blue/grey palette. As with all Bennett’s dramas the dialogue is a treat. The film is now available on DVD in the Alan Bennett at the BBC collection.

Tim Roth as Gregor Samsa.

Metamorphosis (1987), dir: Jim Goddard.

Another TV drama based on one of Steven Berkoff’s three stage adaptations of Kafka in which he also plays the part of Mr Samsa. Berkoff’s preference for physical theatre means there are no insect suits or special effects here, Gregor Samsa’s insectile nature is conveyed entirely through Tim Roth’s energetic performance, with shrieks, twisted limbs, and a climbing frame for when he needs to scuttle up the wall or hang from the ceiling. Not available on DVD but it’s scattered around YouTube if you can be bothered.

The Trial (1991), dir: Steven Berkoff.

Another Berkoff adaptation which is available on DVD from his own company. As with his Salome, this is a filmed stage performance and highly recommended for its fidelity to the book, although of the two I prefer the Oscar Wilde play. Berkoff’s great innovation is the bare stage where the only props are a couple of chairs and a number of tall metal frames, one for each performer, which the actors use to create doors, windows, picture frames and even a series of moving corridors. Berkoff himself plays Titorelli the painter as a hyperactive Dalí type.

Kafka (1991), dir: Steven Soderbergh.

A cult film of mine which I’ve written about before so there’s no need to go into great detail. It’s a shame that Daniel Day-Lewis couldn’t have played Kafka in this one instead of Jeremy Irons who does a decent job but always seems slightly wrong for the part. Ian Holm in Brazil had a role named after Terry Gilliam’s MAD-magazine mentor Harvey Kurtzman; here Holm is named after one of the great silent film directors in the role of the enigmatic Doctor Murnau. Shot on location in Prague.

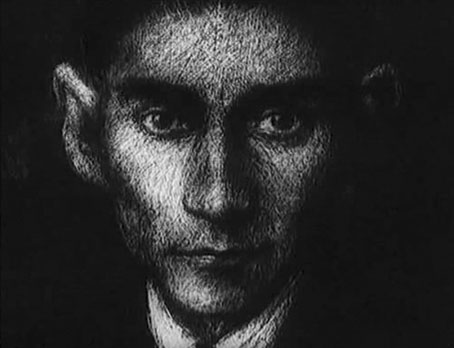

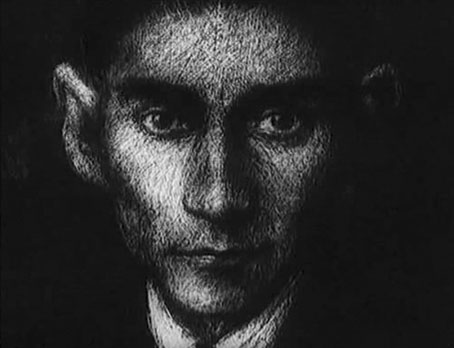

Franz Kafka (1992), dir: Piotr Dumala.

After all the fake Kafkas, something which is at least close to genuine article in a short and wordless animated film by Piotr Dumala. Can be watched in its entirety here.

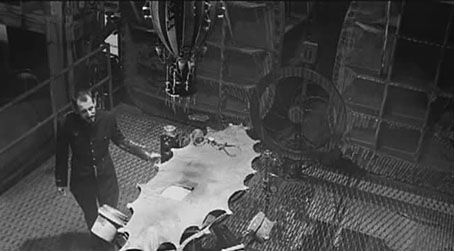

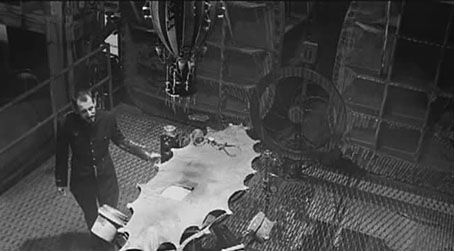

Zoetrope (1999), dir: Charlie Deaux.

Kafka’s In the Penal Colony is moved from its sun-blasted location to what looks like the interior of a power station in Charlie Deaux’s frenetic adaptation. The emphasis is very much on the industrial with the film nodding as much to David Lynch as Franz K. (And whatever happened to David Lynch’s proposed adaptation of The Metamorphosis?) The rumbling, clanging soundtrack by Lustmord provides the requisite Alan Splet-like atmospherics. Available on DVD from Soleilmoon.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Die Andere Seite by Alfred Kubin

• Designs on Kafka

• The Hourglass Sanatorium by Wojciech Has

• Kafka’s porn unveiled

• A postcard from Doctor Kafka

• Alexandre Alexeieff and Claire Parker

• Hugo Steiner-Prag’s Golem

• Steven Soderbergh’s Kafka

• Kafka and Kupka