The enigmatic hibiscus: Le Testament d’Orphée (1960).

Here’s a conundrum for you: what connects Jean Cocteau, Ravi Shankar, Doctor Who and March of the Penguins? Read on and all will become crystal clear….

This latest { feuilleton } examination of the byways of musical culture isn’t concerned so much with an individual artist, more with a particular sound. Timbre is the keyword here, usually defined as “the distinctive property of a complex sound”. My own interest in unusual timbres goes back to a childhood fascination with those corrugated plastic tubes which produce a variable, high-pitched drone when whirled over the head. The principal characteristic of this sound is the purity of its tone, a quality also found in electronic music, of course, but that purity was known hundreds of years before synthesizers in the music produced by glass instruments. This post isn’t intended as a detailed history of glass instrumentation and glass music, the subject is bigger than you might imagine. Consider this an aperitif, and an account of the solving of a nagging musical mystery.

The conundrum begins when I returned from Paris two years ago with a DVD of Cocteau’s Le Testament d’Orphée, a film unavailable on disc at that time in the UK. The French connection here is an appropriate one, as will become evident. One of the many motifs in the film is the recurrent image of a hibiscus flower given to Cocteau by actor Edouard Dermithe. Cocteau carries the flower with him in subsequent scenes and whenever it’s shown in close-up a peculiar musical signature of three short notes is played. I thought at first this might be an electronic sound but there seemed to be no way to find out for sure. It transpires that the answer was hiding in plain sight all the time but the roundabout discovery has taken me into areas I might otherwise have missed. Whatever the solution, I was sufficiently intrigued to sample it and make it the text (SMS) ringtone for my phone.

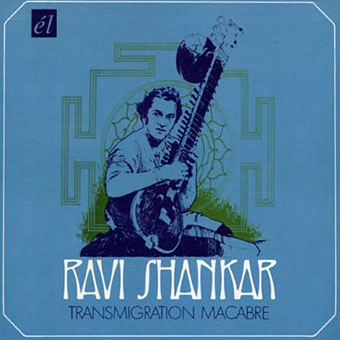

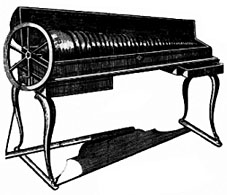

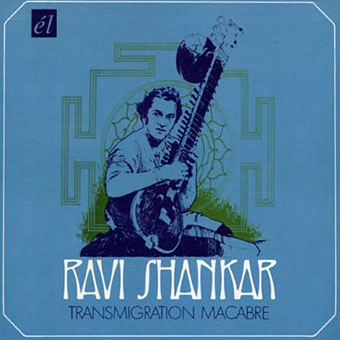

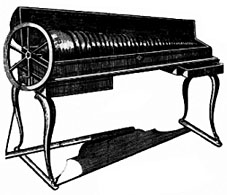

The next piece of the puzzle was also film-related and came with the discovery of a Ravi Shankar album, Transmigration Macabre. This short work was recorded in 1967 as the score for a British “art film”, Viola, which is sufficiently obscure to be absent from IMDB’s database. The second track on the album, Fantasy, was a revelation; in place of sitar, the whole piece is played on the same instrument that was used to create the Cocteau sound…but what was it? My mp3 files were lacking the necessary credits so I was left guessing. Was it some strange Indian keyboard? Something played through a ring modulator? Mentioning this mystery to my good friend Gav—he of the Metabolist vinyl, Igor Wakhévitch albums, vast Jandek obsession, and the only person I know who might care about such a pressing issue, never mind be able to solve it—prompted the suggestion that the instrument might be a glass harmonica (below). Well yes and no; the sound of a glass harmonica (or hydrocrystalophone) is close but has a higher register which lacks the depth of the Cocteau/Shankar instrument. Björk used one for a track on Homogenic and as an instrument it’s certainly unusual and fascinating.  Contemporary models are based on Benjamin Franklin’s treadle-operated machine which turned the familiar arrangement of tuned wine glasses or “glass harp” (something Björk has also used) into a proper musical instrument. Franklin’s machine uses a foot-powered treadle to turn an iron spindle holding 37 nested bowls; the bowls are soaked with water and wet fingers applied to the bowl edges to create the sounds. The unique timbres produced by the instrument aren’t so surprising to an audience familiar with electronic sounds but were novel enough in the 18th and 19th century to inspire rumours of the instrument causing madness in players and listeners. Wikipedia has a wonderful example of glass harmonica playing which demonstrates its ethereal quality. There’s something very magical about sounds produced by non-electronic means which yet seem so otherworldly; theremins can sound shrill and graceless in comparison. That Wikipedia page also contains the solution to my musical mystery but the answer for me came via a different source.

Contemporary models are based on Benjamin Franklin’s treadle-operated machine which turned the familiar arrangement of tuned wine glasses or “glass harp” (something Björk has also used) into a proper musical instrument. Franklin’s machine uses a foot-powered treadle to turn an iron spindle holding 37 nested bowls; the bowls are soaked with water and wet fingers applied to the bowl edges to create the sounds. The unique timbres produced by the instrument aren’t so surprising to an audience familiar with electronic sounds but were novel enough in the 18th and 19th century to inspire rumours of the instrument causing madness in players and listeners. Wikipedia has a wonderful example of glass harmonica playing which demonstrates its ethereal quality. There’s something very magical about sounds produced by non-electronic means which yet seem so otherworldly; theremins can sound shrill and graceless in comparison. That Wikipedia page also contains the solution to my musical mystery but the answer for me came via a different source.

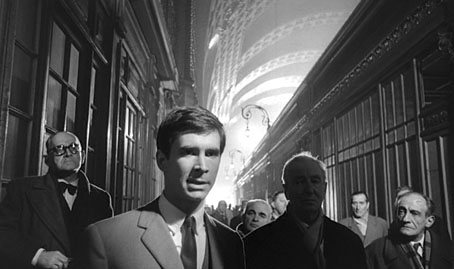

left: Structures Sonores No. 4 by Lasry Baschet; right: La Marche de l’Empereur by Emilie Simon.

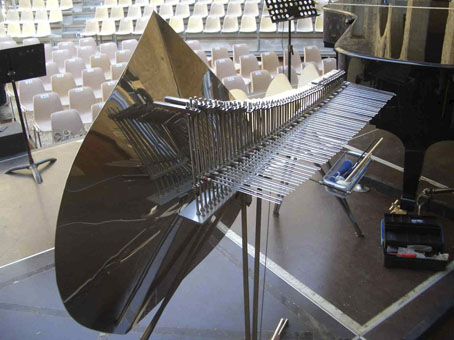

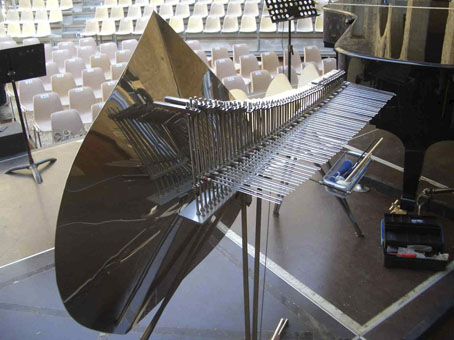

Discussion of the Cocteau/Shankar question prompted the remembrance of another soundtrack with a similar quality, a theme for a long-running TV programme for British schools called Picture Box. The programme itself was undistinguished (short films from around the world) but Gav and I had always been intrigued by the strange title music which accompanied film of a spinning antique glass case. That title sequence had to be on YouTube, right? Of course it is, together with the reminiscences of people traumatised when they were kids by the “scary” title music. And this was indeed the Cocteau/Shankar instrument! A quick jump to TV Cream supplied the vital details: the theme was Manege from Structures Sonores No. 4 by Lasry Baschet, a 10-inch vinyl release from the 1960s on Disques Bam. So the instrument in question was revealed as—voila!—the Cristal Baschet or Cristal as it’s now known. Sure enough, looking again at the opening credits of the Cocteau film, Lasry Baschet are mentioned for their “Structures Sonores”. Georges Auric is the credited music composer yet having watched the film again recently I noticed brief snatches of Cristal music in two scenes. The Lasry component of Lasry Baschet was Jacques and Yvonne Lasry, two Cristal players and composers, while Baschet was Bernard and François Baschet, a pair of inventors who developed the instrument in 1952. “For 150 years,” François Baschet said in a 1962 TIME interview, “the only instruments that have been invented have been the saxophone, the musical saw and concrete and electronic music. Why?” Why, indeed. The Cristal was one of their answers to that question. Contemporary Cristal player Thomas Bloch describes the instrument:

The Cristal Baschet (sometimes called Crystal Organ and in English, Crystal Baschet) is composed of 54 chromatically tuned glass rods, rubbed with wet fingers. So, it is close to the Glassharmonica. But in the Cristal Baschet, the vibration of the glass is passed on to the heavy block of metal by a metal stem whose variable length determines the frequency (the note). Amplification is obtained by fiberglass cones fixed on wood and by a tall cut out metal part, in the shape of a flame. “Whiskers”, placed under the instrument, to the right, increase the sound power of high-pitched sounds.

A modern Cristal from the player’s side.

The original glass rod “keyboard” was vertical which must have made playing difficult. This was changed to a horizontal arrangement in 1970. It’s the combination of metal and glass that gives the instrument its distinctive timbre, with the large metal amplifying cones adding the tonal richness which the glass harmonica lacks. This page notes its use on the Shankar album, and we also learn that original Doctor Who producer Verity Lambert had been eager in 1963 to commission Lasry Baschet to create a theme for the BBC’s new science fiction series. The idea was dropped when negotiations proved difficult so Ron Grainer and Delia Derbyshire (the subject of an earlier post) were called in to create their now famous theme tune.

Thomas Bloch with one of his Cristals.

The Cristal is still in use today with Thomas Bloch and Michel Deneuve being two of its principal virtuosi. Bloch also plays the glass harmonica and that other fine example of Francophone ethereality, the Ondes Martenot, and has a great set of YouTube performances including this multi-Cristal concert. France is certainly a country that enjoys these kinds of sound and all the main players of the Cristal seem to be French. It’s significant that the sole example of glass instrumentation on Gravikords, Whirlies & Pyrophones: Experimental Musical Instruments, a 1996 book and CD documenting unusual instruments, was by Jean-Claude Chapuis, another glass virtuoso who also plays the Cristal. It’s significant too that the Cristal is most widely-known for its use in soundtracks. This is often the fate of new or experimental instruments; Oskar Sala’s Trautonium is permanently linked to Alfred Hitchcock after it was used to generate some of the sounds for The Birds. And I was reading recently about the Hang, a metal bowl used by Cliff Martinez in his score for Steven Soderbergh’s Solaris. Emilie Simon‘s marvellous, award-winning score for the original (French) release of March of the Penguins (2005) featured Thomas Bloch playing his Cristal, glass harmonica and Ondes Martenot. (Simon’s score was deemed by Hollywood to be too weird so the film was re-scored for its American incarnation.)

All this Cristalography leaves little room for an examination of other glass musicians or music, some of whom are considerably more avant garde (and often less harmonious) in their approach. As I said, it’s a big field but mention should at least be made of The Glass World of Anna Lockwood (1970) (later Annea Lockwood), a collection of atonal scrapes, shrieks and clangs produced by various pieces of glass, including wine glasses. Then there’s Angus Maclaurin’s excellent Glass Music (2000), a unique work which Pitchfork called “an album of beautiful claustrophobia”. And Harry Partch, of course, with his Cloud Chamber Bowls. Lastly, minimalist composer Daniel Lentz wrote a stunning wine glass composition, Lascaux, which has recently been reissued on CD. An earlier version of that piece required the glasses to be filled with wine, not water, and for the players to drink the wine at various moments during the performance; this would alter the sound of the instruments and affect their playing.

Much of this activity, you’ll note, is lodged firmly at the “serious”, classical end of the musical spectrum, despite the efforts of Björk and Damon Albarn (a Cristal fan apparently) to broaden musical horizons. We’re still awaiting the Joanna Newsom of the Cristal, someone who can take the instrument as their own and lift it away from the classical repertoire and the realm of soundtrack novelty. Throw away your guitars, boys and girls, the crystal world has much more to offer.

Thanks to Gav for his invaluable record collection and assistance with this piece.

Further listening:

• Difference Tone: A Cristal Concert | Streaming audio at the Internet Archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• A cluster of Cluster

• Max Eastley’s musical sculptures

• The Avant Garde Project

• White Noise: Electric Storms, Radiophonics and the Delian Mode

• Chrome: Perfumed Metal

• Exuma: Obeah men and the voodoo groove

• Metabolist: Goatmanauts, Drömm-heads and the Zuehl Axis

• The Ondes Martenot

• La Villa Santo Sospir by Jean Cocteau

• The music of Igor Wakhévitch

Contemporary models are based on Benjamin Franklin’s treadle-operated machine which turned the familiar arrangement of tuned wine glasses or “glass harp” (something

Contemporary models are based on Benjamin Franklin’s treadle-operated machine which turned the familiar arrangement of tuned wine glasses or “glass harp” (something