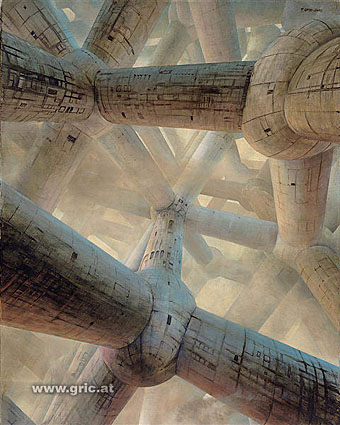

Julian House artwork for Other Voices, a new singles series on the Ghost Box label. Other Voices 01 is a collaboration between Sean O’Hagan of the High Llamas and Jon Brooks of The Advisory Circle.

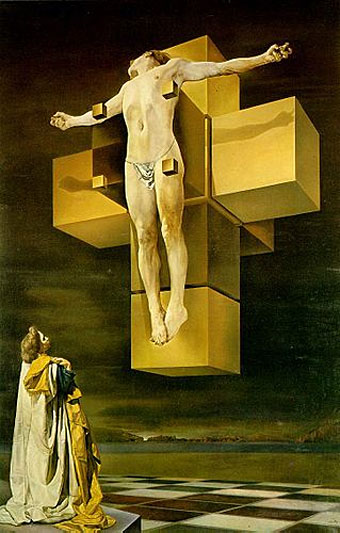

Last week I linked to a copy Zadie Smith’s new introduction for Crash by JG Ballard. That piece could only be read in full by NYRB subscribers but this week the Guardian has the full text:

I was in college when the Daily Mail went to war with [David Cronenberg’s] movie, and found myself unpleasantly aligned with the censors, my own faux-feminism existing in a Venn diagram with their righteous indignation. We were both wrong: Crash is not about humiliating the disabled or debasing women, and in fact the Mail‘s campaign is a chilling lesson in how a superficial manipulation of liberal identity politics can be used to silence a genuinely protesting voice, one that is trying to speak for us all.

Related: Thomas Jones in 2008 reviewing Miracles of Life:

Despite all the bodily fluids spurted and smeared onto wrecked dashboards, the problem isn’t that it’s too pornographic but that it isn’t pornographic enough: the novel is too conscious of the deeper meaning of the sex and violence for the sex and violence to work as elements in themselves.

The fetishisation of Ballard’s novel (and Ballard’s fetishes) show no signs of abating: B-Movie (Ballardian Video Neuronica), is a short film by John Foxx, Karborn and Jonathan Barnbrook.

• Last Thursday I was watching a live performance by Pye Corner Audio and Not Waving, so it’s good to find this mix by the pair surfacing in the same week. Kudos to the latter for choosing something by Chrome. More mixes: FACT mix 468 by Throwing Snow, and Secret Thirteen mix 120 by Drøp.

• Ellen Datlow’s horror anthology, Lovecraft’s Monsters, continues to gather plaudits. Among recent reviews there’s Matt Barone at Complex who included the book in his Year’s Best Genre Fiction Books (So Far) list, and also praised my illustrations.

In recent years, many of the people on book covers have been women without faces. So prevalent is this visual cliché that the publishing industry has cycled through at least two well-documented iterations. The first, the Headless Woman, features some poor thing cut off above the neck, like the swimsuit-clad beachgoer on Alice Munro’s story collection “The View from Castle Rock.” The website Goodreads’s Headless Women page has 416 entries. Last year, the Headless Woman was supplanted by the Sexy Back, in which a woman is shown from behind, often gazing out over a vista.

Eugenia Williamson on the packaging of books for a female readership.

• The latest Taschen volume from Dian Hanson, editor of (among other titles) The Big Penis Book, is My Buddy. World War II Laid Bare, featuring photos from the archives of Michael Stokes. World of Wonder has pages from the interior.

• I Have Walked This Body by Jenny Hval and Susanna is a track from a forthcoming album inspired by Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid’s Meshes of the Afternoon. It sounds fantastic so I’m looking forward to hearing more.

• If you have a spare half-million dollars, and don’t mind the possibility of possession by murderous supernatural entities, the Palmer house from Twin Peaks is for sale.

• Read an extract from Season of the Witch: How the Occult Saved Rock and Roll by Peter Bebergal.

• The Stars and Their Courses: over six hours of the Nevada night sky in 4k definition.

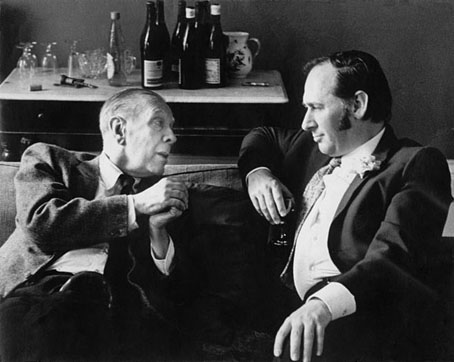

• Lee Siegel on the fraught friendship of TS Eliot and Groucho Marx.

• Harmony Korine talked to Kenneth Anger for Interview Magazine.

• New Scientist: How magic mushrooms induce a dream-like state.

• 3D-print your own Marcel Duchamp chess set.

• Crash (1980) by Tuxedomoon | Burning Car (1980) by John Foxx | A Crash At Every Speed (1994) by Disco Inferno | Burning Car (Dubterror Remix, 2008) by John Foxx