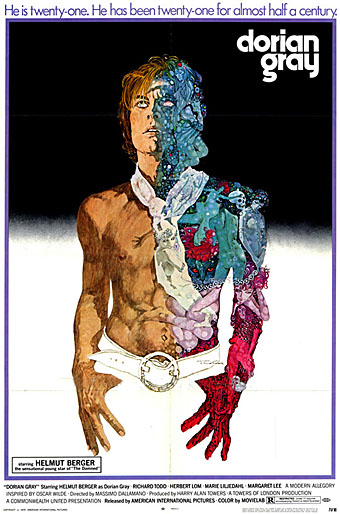

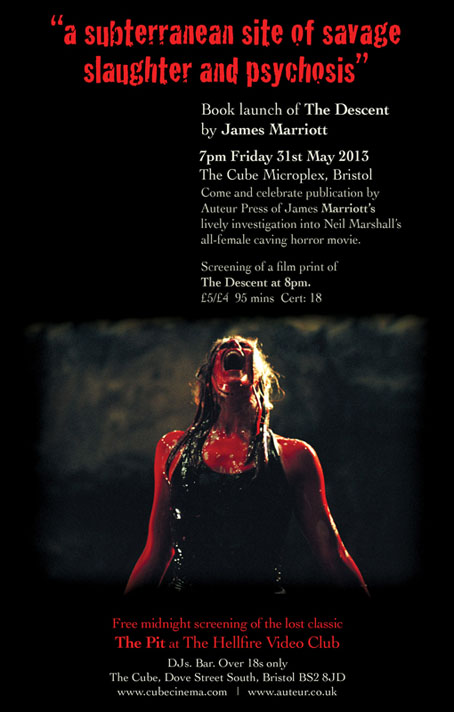

My friend James Marriott died last year. He was 39. His final book, The Descent, a study of Neil Marshall’s acclaimed horror film, is launched on Friday at the Cube Microplex in Bristol. The book is published by Auteur, a UK imprint, in their Devil’s Advocates series. James was finishing the book a year ago this month, and sent me a late draft for comments. In addition to examining Marshall’s film in detail he also looks at its sequel and explores the micro-genre of cavern-oriented horror. When it came to literature James preferred Robert Aickman and Thomas Ligotti; he enjoyed their cinematic equivalents too but he also had a great appetite for horror films of any description, and would happily wade through hours of giallo trash in the hope of finding something worthwhile. I miss our long, digressive email exchanges, and the opportunity they afforded to swap new discoveries.

• “For artists not working in digital media — those who cut, build, draw, paint, glue, bend, and make things in the more traditional manner — there is something of a ‘Surrealist’ popularity at hand today,” says John Foster.

• At Open Culture: Duke Ellington’s Symphony in Black starring a 19-year-old Billie Holiday, and Nina Simone performs six songs on The Sound of Soul (1968).

• I’m not remotely interested in Baz Luhrman’s latest but I do like the Art Deco graphics and logos created by Like Minded Studio for The Great Gatsby.

• Alejandro Jodorowsky: “I am not mad. I am trying to heal my soul”

• The Clang of the Yankee Reaper: Van Dyke Parks interviewed.

• A 45-minute horror soundtrack mix by Spencer Hickman.

• At But Does It Float: Album art by Robert Beatty.

• Topological Marvel: The Klein Bottle in Art

• Anne Billson on The Art of the Voiceover.

• Soviet board-games, 1920–1938

• A Brief History of Robot Birds

• Le Chemin De La Descente (1970) by Cameleon | Descent Into New York (1981) by John Carpenter | The Descent (1985) by Helios Creed