Another Peter Brook film, and a very strange one it is, not for its content but more for the way you wonder how the director managed to get anyone to pay for it, and what kind of audience it was supposed to be aimed at. Meetings with Remarkable Men is a book by GI Gurdjieff which is supposedly an account of the mystic’s early life and youthful questing for truth, although there’s always been debate about how much of it was intended as straight autobiography and how much as symbolic instruction. I’ve known about Brook’s film since it was first released in 1979 but its resolutely uncommercial nature means it never had a wide cinema release, and I’ve never seen it listed for TV screening either.

I’ve not read Gurdjieff’s book but know enough about the man’s life and general philosophies to at least appreciate Brook’s film. Many other viewers would have considerable problems when Brook and screenwriter Jeanne Salzmann make no attempt to elaborate on the details of Gurdjieff’s quest. From youthful worries about life and death, to a search for a secret brotherhood who may have preserved ancient philosophies, the film illustrates scenes in the sketchiest manner: old volumes are bought then discarded; a map is sought then forgotten; gurus are pursued only to be found unsatisfying. For a film about enlightenment it’s surprising to be left so unenlightened. Much of the film was shot on location in Afghanistan shortly before the Soviet invasion, and at times the film seems like a chase from one dusty location to another with little reason or purpose.

The most bizarre feature of all is the cast: Gurdjieff is portrayed by a Serbian actor, Dragan Maksimovic, but many of the other roles provide cameos for an array of British talent, not least Terence Stamp in between appearances as General Zod in the Superman films. Elsewhere there’s Warren Mitchell (!) playing Gurdjieff’s dad, Colin Blakely, Marius Goring, Ian Hogg (who was also in The Marat/Sade), and most surprising of all since I was watching him recently in Quatermass and the Pit, Andrew Keir as the head of the mysterious Sarmoung Monastery. The cast alone helps maintain some interest although at times it’s like one of those all-star features such as Around the World in Eighty Days where you’re wondering who’s going to turn up next. For those whose curiosity is piqued, the entire film is on YouTube.

Previously on { feuilleton }

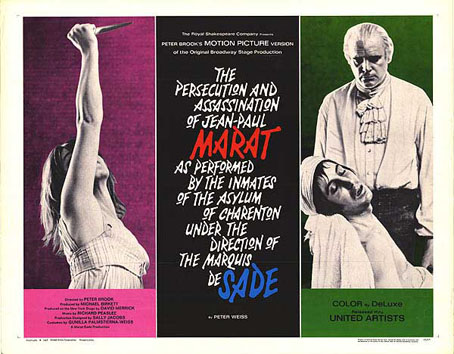

• The Marat/Sade