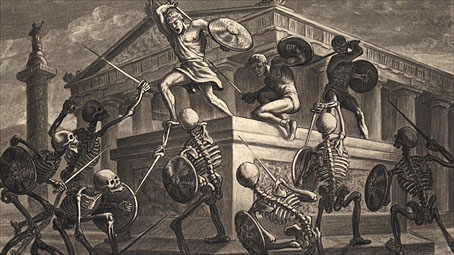

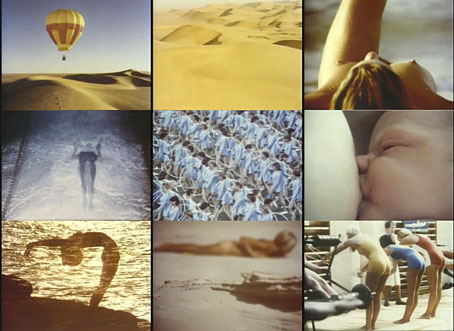

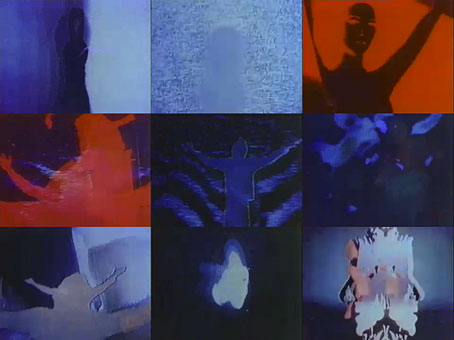

The DVD collection of films by Piotr Kamler turned up last week so I’ve been alternating viewing of that with shorts by Patrick Bokanowski. The latter is less an animator than a filmmaker who uses animation or film effects to achieve his aims, together with masks and very stylised performances. Bokanowski’s early film La femme qui se poudre (The Woman Who Powders Herself, 1972) runs for 15 minutes, and is as remarkable in its own way as his feature-length L’Ange (1982). La femme qui se poudre has the same masked figures engaged in activities which often lack easy interpretation; in both films the atmosphere can shift from absurdity to the edge of horror and back again. For me what’s most remarkable about this particular short is the way it anticipates both Eraserhead and the early films of the Brothers Quay yet still seems little known. The Quays are on record as admiring L’Ange but I’ve yet to see any sign that David Lynch knew of this film in the 1970s. I’d be wary of assuming that Lynch was imitating Bokanowski, artists are quite capable of finding themselves working in similar areas independently.

Films of this nature always benefit from well-matched soundtracks: Piotr Kamler uses recordings by different electronic composers; Eraserhead had Fats Waller and the rumblings and hissings of Alan Splet; the Quays have unique compositions by Lech Jankowski. La femme qui se poudre and L’Ange have outstanding soundtracks by Michèle Bokanowski, the director’s wife and an accomplished avant-garde composer. Her work is as deserving of further attention as that of her husband. DVDs of L’Ange and a collection of Patrick Bokanowski’s short films may be purchased here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Le labyrinthe and Coeur de secours

• Chronopolis by Piotr Kamler

• Brothers Quay scarcities

• Patrick Bokanowski again

• L’Ange by Patrick Bokanowski