If you’ve ever watched The Man Who Fell to Earth then you’ve heard music by Japanese percussionist and composer Stomu Yamash’ta. The opening scene where David Bowie’s duffle-coated alien stumbles down a hillside (falling to earth for a second time) is scored with the first few minutes of Poker Dice, the opening track on Yamash’ta’s Floating Music album; more Yamash’ta pieces are heard later in the film. Floating Music has just been reissued on CD by Cherry Red in Seasons, a box set which contains all seven of the albums Yamash’ta recorded for the Island label from 1972 to 1976, with each disc housed in a facsimile card sleeve.

Stomu Yamash’ta’s artistic profile was very high in the 1970s, high enough to make his apparent disappearance in the decade that followed an unusual thing. Unusual for me, anyway. I only started to notice his name in the early 1980s, mostly in connection with feature films, and couldn’t work out why he was no longer mentioned anywhere as an active artist. In addition to the Roeg soundtrack he plays on the soundtracks for Robert Altman’s Images (1972) and Saul Bass’s Phase IV (1974); he’s also one of the performers on the Peter Maxwell Davies score for The Devils (1971) although Ken Russell’s film gets to be so chaotic I’ve yet to identify his contribution. Later in the decade Yamash’ta was the only non-Western artist to appear in the final episode of Tony Palmer’s television history of pop music All You Need Is Love, in a programme that explored new musical directions. Away from films and TV there were numerous concerts; Yamash’ta’s history as a percussion prodigy in the 1960s had seen him performing compositions by Peter Maxwell Davies and Toru Takemitsu when he was still in his teens. His energetic performances gave way to a frenzied recording schedule—in 1971 alone he recorded six studio albums—which culminated in 1976 with the founding of Go, a short-lived jazz-fusion supergroup whose lineup included Steve Winwood, Al Di Meola, Michael Shrieve, and (surprisingly) Klaus Schulze.

Yamash’ta’s “disappearance” in the 1980s was really a retreat from the spotlight after a decade-and-a-half of almost continual public activity. He returned to Japan where he continued recording but gravitated away from jazz and avant-garde music towards the spiritual side of Japanese culture. Most of his albums since 1980 have only been Japan-only releases, another factor contributing to his obscurity elsewhere. More recently he’s taken to playing the Sanukitophone, a bespoke percussion instrument made from a variety of volcanic rock unique to the Japanese archipelago.

Freedom Is Frightening (1973), one of three Yamash’ta albums with cover designs by Saul Bass.

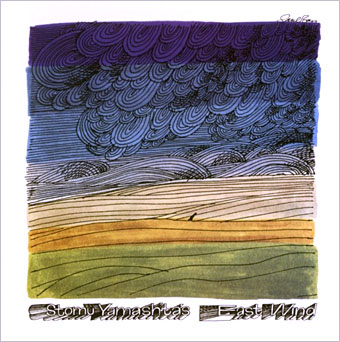

The albums in the new box set encapsulate what might be called Yamash’ta’s “Kozmigroov” period, although Yamash’ta’s name is absent from the generally thorough and wide-ranging Kozmigroov Index. This is also his most commercial period. Prior to 1972 Yamash’ta’s recordings were soundtracks, performances with orchestras or improvised freakouts; from 1980 his music seems to be predominantly meditational (“New Age”, if you must) but I’ve not heard most of it so can’t say much about it. Kozmigroov is jazz fusion at core, usually combining a variety of disparate influences, which is what you have here: extended arrangements of jazz, funk, soul, rock, electronics, and occasional moments of traditional Japanese music. The continually changing group names testify to a restless nature: Floating Music (1972) by Stomu Yamash’ta & Come To The Edge (a British jazz group), Freedom Is Frightening (1973) by Stomu Yamash’ta’s East Wind, The Soundtrack From “The Man From The East” (1973) by Stomu Yamash’ta’s Red Buddha Theatre, One By One (1974) by Stomu Yamash’ta’s East Wind, and Raindog (1975) by Yamashta [sic]. Then there’s the self-titled Go album (with a cover design by Saul Bass) and its live counterpart, Go…Live From Paris. (A third and final album by the group, Go Too, was released on Arista so isn’t included in this set.) The sound evolves from semi-improvised instrumentals on the first few albums to songs and more rock-oriented arrangements on Raindog and the Go releases, with the Steve Winwood songs on the latter coming across as a step into more predictable territory compared to the earlier recordings. The Go live album is much better than the uneven studio set, a sustained suite of songs and instrumentals linked by Klaus Schulze’s synthesizers; Schulze gets a big cheer when the band is introduced. If you like jazz fusion there’s a lot to enjoy in this box, a third of which I hadn’t heard before. Dunes, the opening track on Raindog, unfolds over 15 minutes with an insistent groove that brings to mind the Mahavishnu Orchestra and early Santana, although Maxine Nightingale is a better singer than anyone on the Santana albums. And if you are familiar with The Man Who Fell to Earth then you get all of Yamash’ta’s music from the soundtrack scattered across these albums, most of which is only heard as extracts during the film.

With the recent reissue of Sunrise From West Sea “Live” I’m tempted to think that we might be due for a resurgence of interest in Stomu Yamash’ta’s music, but the prior availability of the Seasons albums as individual CDs doesn’t appear to have prompted a clamour for more. There’s a lot more out there, however, especially the rare Japanese releases from the early 1970s. Follow the links below for more detail.

• The Infinite Horizons of Stomu Yamash’ta by Gregor Meyer.

• The Strange World of…Stomu Yamash’ta by Miranda Rimington.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Devils on DVD

• Directed by Saul Bass

• Saul Bass album covers

• Images by Robert Altman