Last year I was asked to write something about my favourite horror comics for Nørd Nyt, a Danish comics zine. I’d pretty much forgotten about this until the printed copy arrived, so here’s my piece in English, a choice of three favourite horror stories.

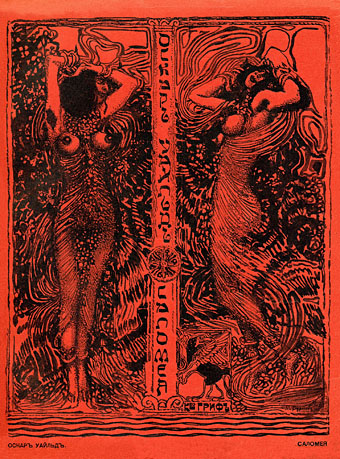

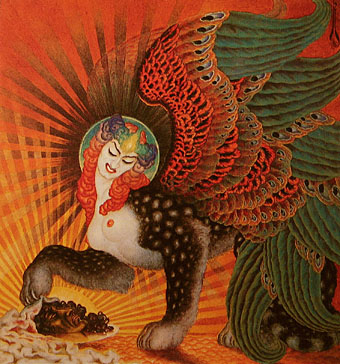

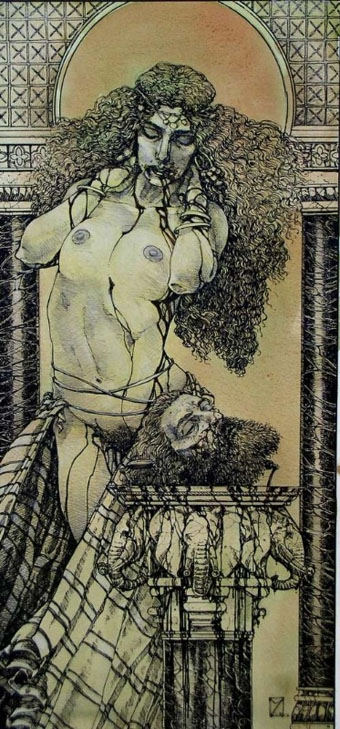

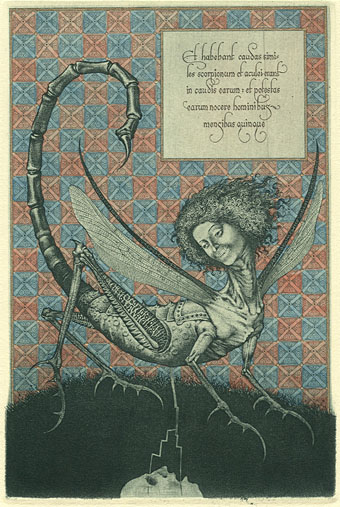

The Dunwich Horror by Breccia (1973)

The October 1979 issue of Heavy Metal magazine came as a revelation. I’d only bought a few issues prior to this, and seeing an entire magazine devoted to HP Lovecraft seemed far too good to be true. Lovecraft art is so common now that it needs to be emphasised how scarce this kind of illustration used to be, the most you saw was paperback art of varying quality. There had been a few comic-strip adaptations but they were mostly in American publications or foreign editions I hadn’t seen. As it turned out, Heavy Metal‘s great JK Potter cover promised more than it actually delivered: at least half the magazine was taken up with continuing strips that had nothing to do with Lovecraft, or strips that did little but borrow a few Lovecraftian motifs for a slight horror tale. The one really outstanding piece was Alberto Breccia’s The Dunwich Horror, one of several Lovecraft adaptations the artist produced in 1973. Breccia’s style was sketchy, shadowy and replete with period details. The faces of his characters looked absolutely right for what I still consider to be one of Lovecraft’s darkest stories (people tend to miss the implication that a backwoods magus very nearly destroys humanity). Until I encountered the artists in Heavy Metal I’d given up on comics as an artistic medium, having no time at all for superheroes or the poor science fiction of 2000AD. Artists like Breccia, Moebius and Druillet showed that there was more than one way of drawing imaginative work, that you could use the refined techniques of illustration to tell a story.

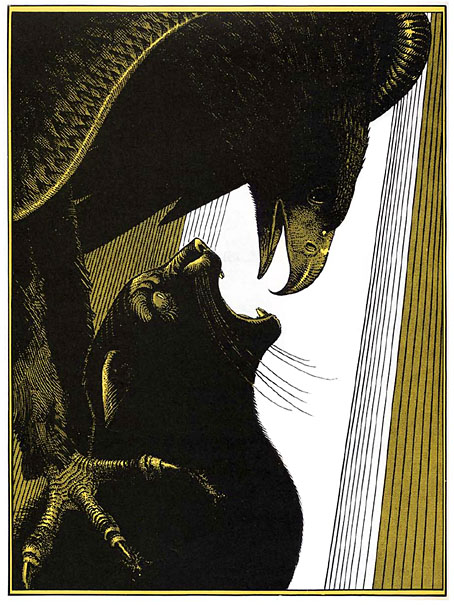

Les Yeux du Chat (The Eyes of the Cat) by Jodorowsky and Moebius (1978)

This story came to my attention when it received its first English translation in the pages of Steve Bissette’s Taboo anthology. It was printed in black on yellow paper, the original French edition having been yellow and black with white highlights. Compared to Jodorowsky’s customary flights of fancy the story is a very simple one, if typically grotesque: a silhouetted figure stands at a tall window overlooking a futuristic (or alien) city, directing with its thoughts the action of an eagle who hunts down a cat in the streets below. The horror comes from the shocking predicament revealed at the end, and the final line of dialogue, although this remains secondary to the formal perfection of the drawing and storytelling. Even by the standards of Moebius’s meticulous draughtsmanship this is a superbly controlled piece of work. Each spread operates as a kind of split-screen, with the left page showing the dialogue and the silhouetted figure, while the full-page illustration opposite shows a simultaneous moment of action somewhere in the city. One thing I immediately liked about this was Moebius’s architecture which even more than usual manages to seem otherworldly yet completely convincing. Everything we see in this brief tale poses questions that remain unanswered. And like many of the best short stories, a few carefully chosen details can imply an entire world.

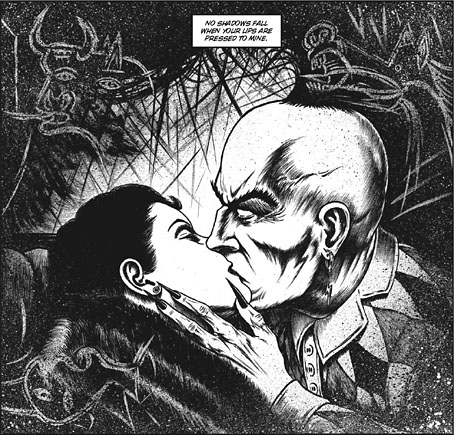

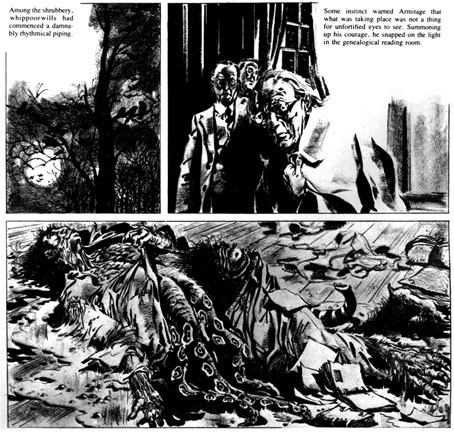

From Hell by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell (1991–1996)

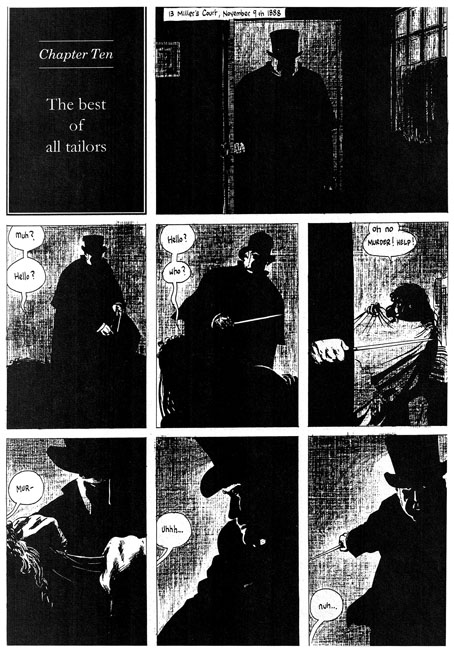

Horror doesn’t have to be delivered within genre stereotypes, in fact these days it’s often better if it isn’t when so many of those stereotypes—vampires and zombies, for example—have been diminished by over-familiarity. From Hell isn’t a horror story per se—it’s self-described as “a melodrama in sixteen parts”—but it debuted in Steve Bissette’s anthology Taboo where the brief was to offer the reader something dark or challenging that they hadn’t seen before. From Hell certainly fulfilled that brief: Alan Moore’s writing has never shied from the dark—consider the nihilistic Rorschach chapter of Watchmen—but this is as black as he gets. Eddie Campbell has been vocal about his dislike of horror stories but he was the perfect artist here with his long experience drawing ordinary human beings rather than posturing superheroes. Together the pair delivered a story that was novelistic in scope and minute in its attention to detail. Most people would have thought they knew more than enough about Jack the Ripper but no other representation has been this thorough in its exploration of all aspects of the case.

Watchmen had already aimed for a panoramic range of characters—from the president to a newspaper-seller—but From Hell went much further and in greater detail, with a scope that ranges from a group of homeless women to the head of the British Empire and all the classes in between. One of the most impressive aspects of the story was its exposure of the awful gap at the heart of previous dramatisations, namely the reduction of the lives of the murdered women to a cast of frequently nameless unfortunates who we glimpse for a moment sidling up an alley before their blood splashes on a wall. Moore’s script showed us (as much as is possible) the real women behind the roll-call of victims, crushed by poverty yet still distinct individuals. Looking for human detail has always been a feature of Moore’s writing, it’s why his work seemed so fresh in the 1980s compared with lesser writers who were simply recycling clichés as though there was no other way to behave. So too with Campbell’s artwork which has never been subject to the exaggerations of the superhero genre. One of my favourite moments in the entire story was utterly human and utterly trivial: the scene in Chapter 3 when Walter Sickert and Annie Crook meet. Annie says “I need a wee” so she hitches up her shift and squats in the road. It’s the accumulation of numerous human moments such as this—the moments that genre comics invariably avoid—that makes From Hell such a powerful and memorable piece of work. Eddie Campbell’s art shows us the true London dark, a city as black and terrible as it would have been in the days before electric light.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Heavy Metal, October 1979: the Lovecraft special