Pink Narcissus (2014) by Tuxedomoon. Design by Flavien Thieurmel.

I’ve never paid much attention to Record Store Day, despite promoting it here on a couple of occasions, and paid even less attention this year now that the event has turned into an opportunity for some of the larger labels to fleece the punters. Consequently, I missed any mention of a new release from Tuxedomoon which Crammed Discs put out as part of this year’s vinyl deluge. I’ve been listening to Tuxedomoon for years so any new release is worthy of attention, especially when their last studio album, Vapour Trails (2007) was a particularly good one, with the added bonus of packaging by Jonathan Barnbrook.

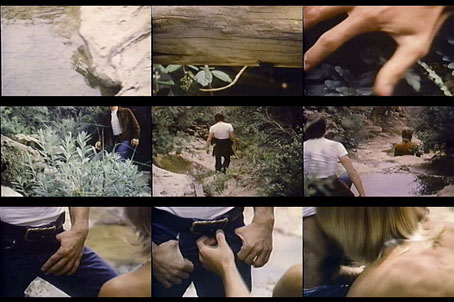

Hanging Off Bed, a still from Pink Narcissus, mid- to late 1960s.

The new album, Pink Narcissus, is a recording of the group’s live soundtrack performance for the film of the same name by James Bidgood, a luscious micro-budget, homoerotic labour-of-love filmed in the 1960s on 8mm in the cramped confines of Bidgood’s New York apartment. The original soundtrack comprises selections of romantic classical music by Mussorgsky and Prokofiev so the replacing of the score isn’t as much of an imposition as it can be when bands co-opt old films. I already liked Bidgood’s film a great deal so Tuxedomoon’s score is like a marriage made in heaven (and they once recorded their own version of In Heaven). Having watched the film synched to the new album I was impressed by how well the group matched the shifting moods. From their earliest releases Tuxedomoon’s music has tended towards the cinematic so you’d expect them to provide a sympathetic treatment; they’ve also recorded a few scores in the past, including one for their own ambitious film/stage performance, Ghost Sonata. But Pink Narcissus matches the scenes much more effectively than the classical selections, the group even work in a pause then a shift to a new style when Bidgood’s star boy, Bobby Kendall, puts a record on his wind-up gramophone. The only drawback in running the music with the film is that the album is 10 minutes short, possibly because of the limitations of the vinyl format. YouTube user bigniouxx has a few brief clips of the live performance at the L’Etrange Festival in Paris.

Blue Boy, a still from Pink Narcissus, mid- to late 1960s.

If the BFI ever reissues the film I hope they consider using the full Tuxedomoon score as an alternative soundtrack the way they did on the Peter de Rome porn films, some of which are scored by Stephen Thrower. Bidgood’s film is still available on DVD with a detailed booklet and a great interview with the director; the BFI also has it on their video-on-demand service. Despite its age and its campy glamour Pink Narcissus is still pretty pornographic in places, not as much as Peter de Rome’s films (or today’s porn, for that matter) but there’s enough wanking and erections to keep it off many TV networks. The album, housed in a great sleeve designed by Flavien Thieurmel, may be bought direct from Crammed Discs.

• James Bidgood’s photography at ClampArt

Previously on { feuilleton }

• William E. Jones on Fred Halsted

• Flamboyant excess: the art of Steven Arnold

• James Bidgood