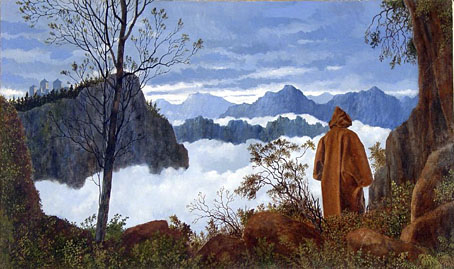

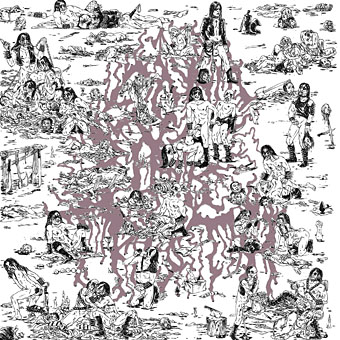

The Philosophers (Homage to Courbet) by Christopher Ulrich. Another great tip from Full Fathom Five.

• “Mushrooms are the only psychedelic drugs that I take, and I don’t take them very often. But I would trust them. Once you’ve done them a few times it’s very easy to feel a sense of entity. You can feel that there is a characteristic in this level of consciousness which almost seems…playful? Or aware, or sometimes a bit spooky.” Alan Moore discussing art and psychedelics in Mustard magazine. Related: “Psychedelics not linked to mental health problems or suicidal behavior: A population study.”

• “Leonora Carrington transcended her stolid background to become an avant-garde star,” says Boyd Tonkin. At the BBC Chris Long looks at Leonora Carrington’s journey from Lancashire to Mexico. The Carrington exhibition at Tate Liverpool opened on Friday.

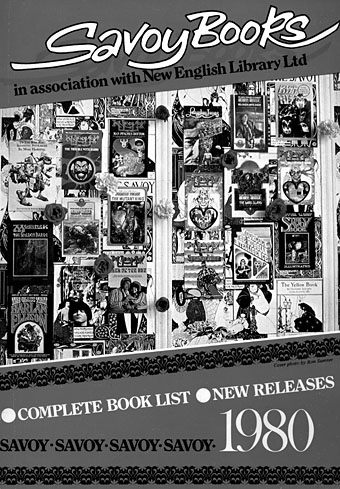

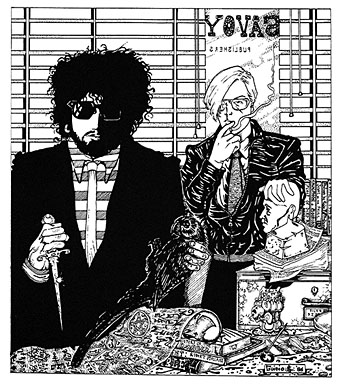

• A Savoyard’s First Brush with Censorship, Clara Casian’s proposed documentary film about Savoy Books, is looking for Kickstarter funding.

Warner suggests that there are four characteristics that define a veritable fairy tale: first, it should be short; second, it should be (or seem) familiar; third, it should suggest ‘the necessary presence of the past’ through well-known plots and characters; fourth, since fairy tales are told in what Warner aptly calls ‘a symbolic Esperanto’, it should allow horrid deeds and truculent events to be read as matter-of-fact. If, as Warner says, ‘the scope of a fairy tale is made by language’, it is through language that our unconscious world, with its dreams and half-grasped intuitions, comes into being and its phantoms are transformed into comprehensible figures like cannibal giants, wicked parents or friendly beasts.

Alberto Manguel reviewing Once Upon a Time: A Short History of Fairy Tale by Marina Warner

• De Natura Sonorum (1976) by Bernard Parmegiani: a free download at AGP of the original vinyl recording, something I overlooked several years ago.

• At Dangerous Minds: Real Horrorshow!: Malcolm McDowell and Anthony Burgess discuss Kubrick and A Clockwork Orange.

• Meeting Bernard Szajner, a short film about the French electronic musician by Tom Colvile, Nathan Gibson & Abdullah Al-wali.

• Dismembrance of the Thing’s Past: Dave Tompkins on John Carpenter’s The Thing.

• That Battle Is Over, a new song by Jenny Hval.

• Mushroom (1971) by Can | The Mushroom Family (2010) by The Time And Space Machine | Growing Mushrooms Of Potency (2012) by Expo ’70