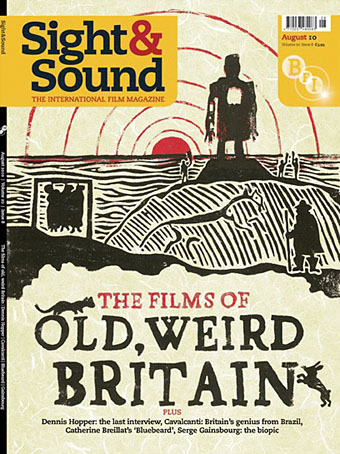

Untitled drawing by Jean Gourmelin.

• Yet another book featuring my design work (interiors this time) has been published in the past week. Leena Krohn: Collected Fiction is an 850-page selection of novels, novel extracts and short works from a prolific Finnish author of the fantastic. Many of the selections are being published in English for the first time:

From cities of giant insects to a mysterious woman claiming to be the female Don Quixote, Leena Krohn’s fiction has fascinated and intrigued readers for over forty years. Within these covers you will discover a pelican that can talk and a city of gold. You will find yourself exploring a future of intelligence both artificial and biotech, along with a mysterious plant that induces strange visions. Krohn writes eloquently, passionately, about the nature of reality, the nature of Nature, and what it means to be human. One of Finland’s most iconic writers, translated into many languages, and winner of the prestigious Finlandia Prize, Krohn has had an incredibly distinguished career. Collected Fiction provides readers with a rich, thick omnibus of the best of her work—including novels, novellas, and short stories. Appreciations of Krohn’s work are also included.

• “Not only is the nature of Rollin’s choice of images close to [Clovis] Trouille’s, the director structures his movies in a similar fashion, crowding his movies with dreamy horror iconography. Rollin has specifically cited the influence of Trouille’s paintings on his work alongside that of other Surrealist painters working in a figurative style.” Tenebrous Kate explores the influences (and influence) of Jean Rollin’s erotic horror films.

• “[Morton] Subotnick might just have been the first person to get a club full of people—including the entire Kennedy family—dancing to purely electronic music when he played his Silver Apples Of The Moon at the opening night of New York’s legendary Electric Circus.” Robert Barry interviews the pioneering composer.

• “What I actually wanted to do was make music that contained all that was new in the 20th century,” says Irmin Schmidt in an interview with Bruce Tantum. Good to read that Rob Young is writing a biography of Can.

• “…gay mainstream culture was never really about expressing individuality, for me. It always seemed very conformist,” says Bruce LaBruce in conversation with Mike Miksche.

• At Dangerous Minds: Paul Gallagher on the making of Ken Russell’s The Devils, and Martin Schneider on the return of Paul Kirchner’s wordless comic strip, The Bus.

• Two years ago a group of Russian urban explorers climbed the Pyramid of Cheops at night. They’ve just returned from South America, and have a report here.

• In the wake of their new album, Kannon, Jason Roche asks “Are drone-metal icons Sunn O))) the loudest band on the planet?”

• Junji Ito returns to horror with two new titles. Related: Fuck Yeah Junji Ito.

• Mix of the week: FACT mix 527 by Jóhann Jóhannsson.

• Anna von Hausswolff‘s favourite albums.

• Touch (Beginning) (1969) by Morton Subotnik | Rapido De Noir (1981) by Irmin Schmidt & Bruno Spoerri | The Gates of Ballard (2003) by Sunn O)))