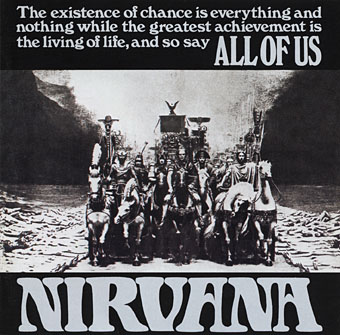

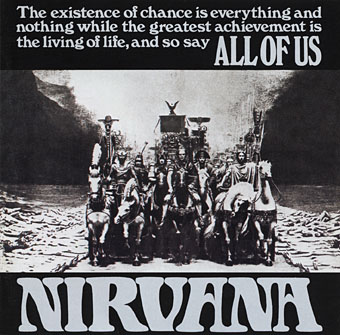

All Of Us by Nirvana (1968).

Every now and then the web’s great proliferation of images serves a useful purpose by solving some minor artistic conundrum. All Of Us is the second album by UK psychedelic band Nirvana (no relation to Kurt and co.) and the striking cover painting—a long line of emperors and warriors from different ages parading down an avenue of corpses—is annoyingly uncredited. The notes for the 2003 CD reissue inform us that “Patrick had found, in an exhibition of Nazi art (in Bremen, Germany), a still shot from a propaganda film directed by Adolf Hitler’s favourite film-maker, Leni Riefenstahl.” Setting aside the bizarre use of such a picture by one of London’s more effete psychedelic groups, I wasn’t convinced that this was a Nazi-era painting. The style is more like a piece of Neoclassical academic art from the late 19th century, and that’s what it turns out to be.

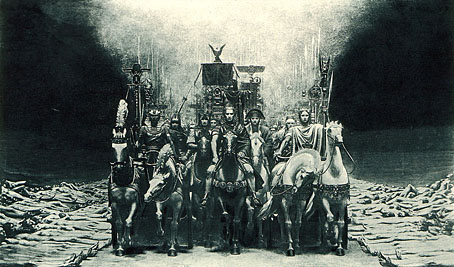

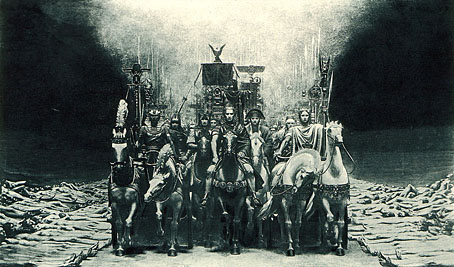

Les Conquérants (1892) by Pierre Fritel. From this Flickr page.

It was a search for works by French academician George Antoine Rochegrosse that turned up a copy of the painting in Google Images. “Aha, it’s Rochegrosse, then!” thought I, only it wasn’t. The picture is entitled Les Conquérants and the artist responsible is one Pierre Fritel (1853–1942) about whom there’s very little information on the web. There is, however, a discussion here which details the painting’s symbolism:

Through the Valley of the Shadow of Death, whose limits are obscured in darkness, advance, hollow-eyed and remorseful, the conquerors of all ages, marching in close ranks between a double row of corpses, stripped and rigid, lying packed close together with their feet toward the procession. In the center of the van rides Julius Caesar, whom Shakespeare has pronounced “the foremost man of all this world.” On his right are the Egyptian called by the Greeks Sesostris, now known to be Rameses II., Attila, “the Scourge of God,” Hannibal the Carthaginian, and Tamerlane the Tartar. On his left march Napoleon, the last world-conqueror, Alexander of Macedon, Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon, that “head of gold” in the great image seen in his vision as interpreted by the prophet Daniel, and Charlemagne, who restored the fallen Roman Empire.

There’s a follow-up discussion on MetaFilter where a commenter makes the Nirvana connection, and the Internet Archive even has the catalogue for the Salon of 1892 which lists the painting’s first public appearance. See a larger monochrome version here. The only mystery now is the whereabouts of the painting itself. Artnet tells us it was sold in 1988, and they have a poor quality colour photo of the picture (below) which looks a lot less dramatic than the moody monochrome reproductions. If anyone knows the current location of Fritel’s canvas, please leave a comment.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The album covers archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The art of Vasili Vereshchagin, 1842–1904