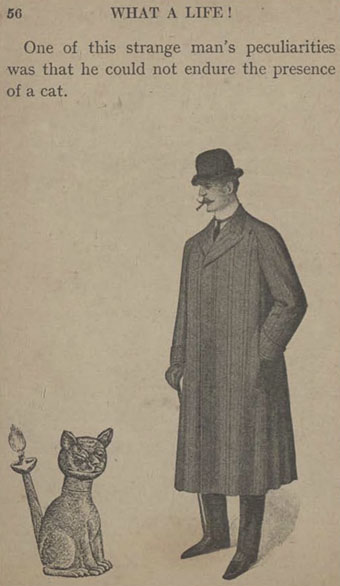

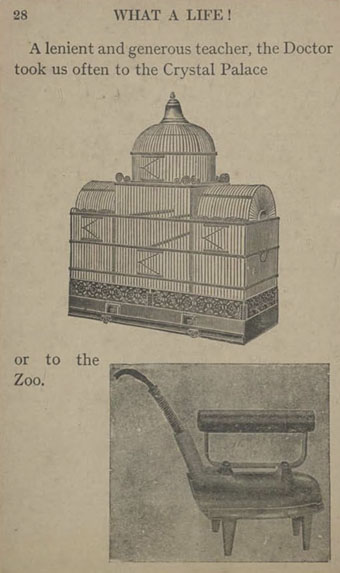

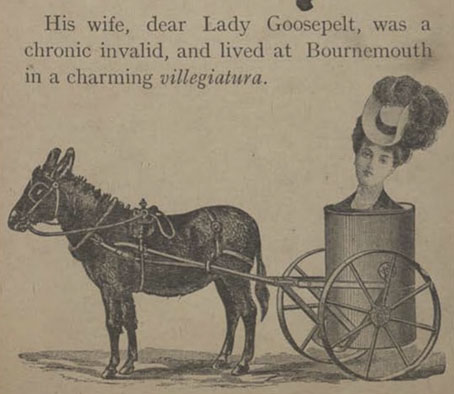

In last week’s post about Norman Rubington/Akbar Del Piombo I said that Rubington’s collages “were probably the first to use the form developed by Max Ernst for explicitly humorous purposes.” That “probably” was well-placed since it turns out that Rubington wasn’t quite the first to reuse engraved illustrations to comic effect, something I was unaware of until a few days ago. What A Life! An Autobiography (1911) is a short book credited to “EVL & GM”, or Edward Verrall Lucas and George Morrow, in which Lucas wrote captions for illustrations selected by Morrow from a catalogue for Whiteley’s, one of the first London department stores. The “autobiography” recounts the upbringing and adulthood of an English aristocrat, Baron Dropmore, with much of the humour being derived not from the text itself but from the mislabelling of various household items. Lucas and Morrow both worked for Punch magazine, and the humour is very much in the older Punch mode but given a fresh twist by the use of pre-existing illustrations.

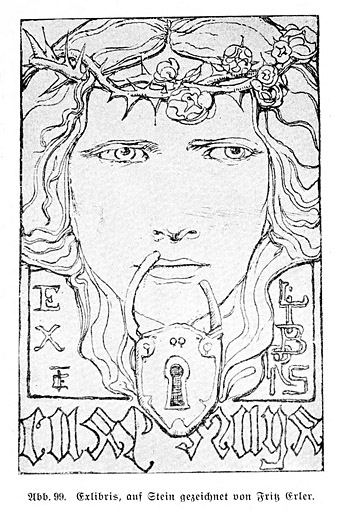

In addition to the mislabelling there’s also some rudimentary collage work from Morrow which is easy to overlook after a century of similar examples. Whiteley’s catalogue seems to have been a more fertile source for this than the publications produced by the store’s rivals. I have a facsimile reprint of the 1895 catalogue for Harrod’s, a literal doorstop of 1000 pages. It’s a useful reference if you want to know how much the upper classes were paying for their goods in the Victorian era but it’s never been very good for collage purposes. This smaller Whiteley’s catalogue has many more illustrations plus a number of those florid title designs festooned with combination ornaments that you often find in 19th-century books.

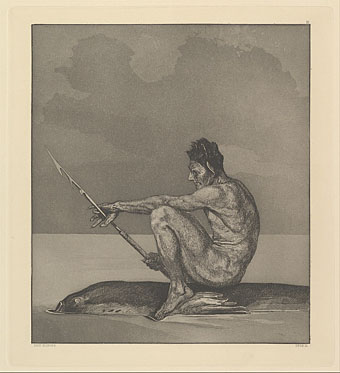

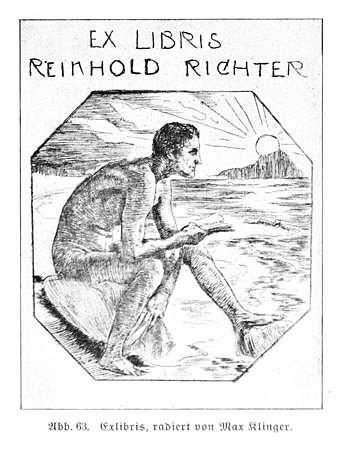

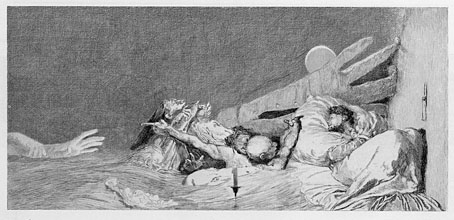

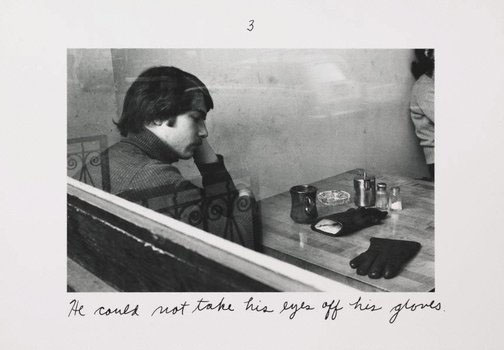

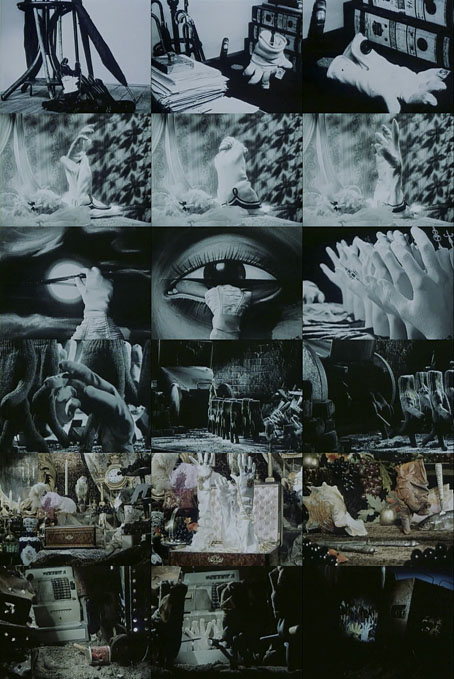

The pages here are taken from a scan at the Internet Archive but What A Life! has been reprinted several times, including an edition published by Dover in 1975 for which John Ashbery provided an introduction. Ashbery enjoyed this kind of pictorial eccentricity; one of his art essays is The Joys and Enigmas of a Strange Hour, an appraisal of A Glove (1881) by Max Klinger, a series of etchings that prefigure the Surrealists in their dreamlike strangeness. Ashbery also made collages of his own, one of which, Summer Dream (2008), contains a detail borrowed from What A Life!

(Thanks to Allan and Andrew for the tip!)

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Fuzz Against Junk & The Hero Maker

• Nathaniel Krill at the Time Node

• Initiations in the Abyss: A Surrealist Apocalypse

• Wilfried Sätty: Artist of the occult

• Illustrating Poe #4: Wilfried Sätty

• Metamorphosis Victorianus

• Max (The Birdman) Ernst

• The art of Stephen Aldrich