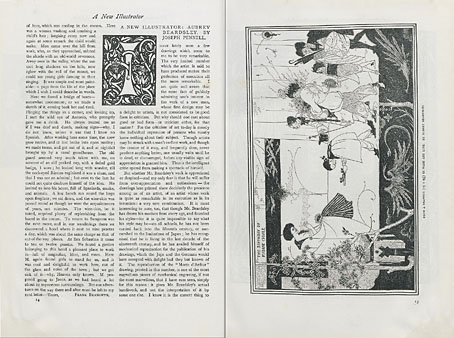

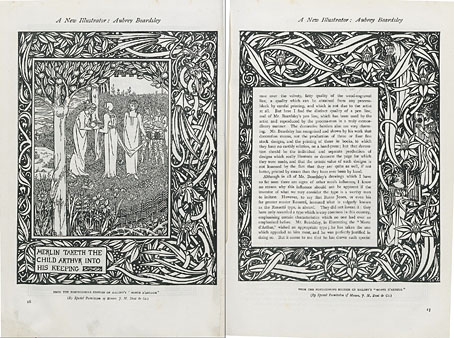

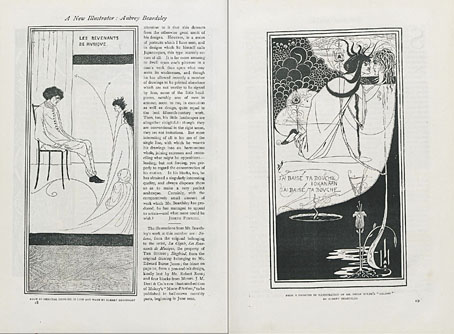

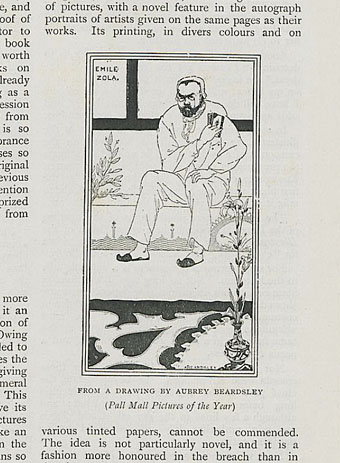

Aubrey Beardsley in the year 1893 was 21, and on the threshold of being catapulted to fame (and notoriety) via his illustrations for Oscar Wilde’s Salomé. Some of Beardsley’s drawings in the distinctive style he called “Japanesque” had already appeared in The Pall Mall Magazine, and he was hard at work on some 600 illustrations and embellishments for Dent’s Le Morte D’Arthur which began publication in 1894. Some of those illustrations are featured in the glowing introduction by Joseph Pennell which appeared in the first issue of The Studio magazine in April 1893 (when Beardsley was still only 20), a title that became the leading showcase for the British end of the Art Nouveau movement in the 1890s. Pennell’s appreciation also included Beardsley’s Joan of Arc’s Entry into Orleans, a piece which showed how much the artist’s early work owed to Mantegna, and the first drawing of Salomé which later helped secure the Wilde commission. The Joan of Arc picture was reproduced as a fold-out supplement in the magazine’s second issue.

All the major Beardsley books refer to Pennell’s article but I’ve never had the opportunity to see it in full until now, thanks to the excellent online archives at the University of Heidelberg. There are many volumes of the international editions of The Studio at the Internet Archive but for some reason these don’t include the early numbers; at Heidelberg we can now browse the missing issues. In the first volume in addition to Beardsley there’s a piece about Frederic Leighton’s clay studies for paintings and sculptures, illustrations by Walter Crane and Robert Anning Bell, and an article on whether nude photography can be considered art. In this last piece several of the examples happen to be provided by Frederick Rolfe aka Baron Corvo, and Wilhelm von Gloeden, two men who we now know had other things on their mind when they were photographing Italian youths.

The collected volumes of The Studio from 1893 to 1898 may be browsed or downloaded here. I’ve not had time to go through the rest of these so I’m looking forward to discovering what else they may contain.

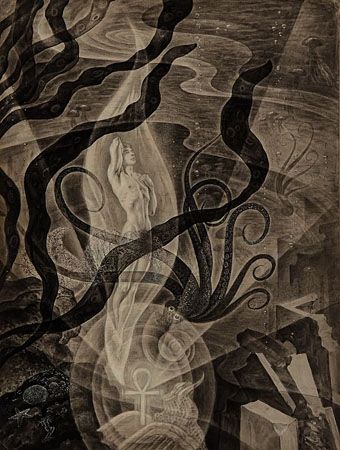

Detail from Joan of Arc’s Entry into Orleans.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Aubrey Beardsley archive