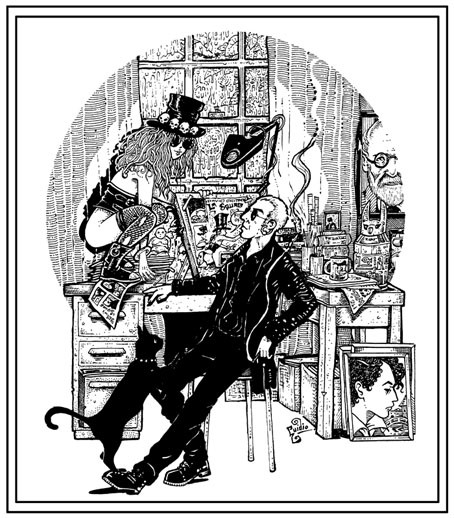

A self-portrait, 2011.

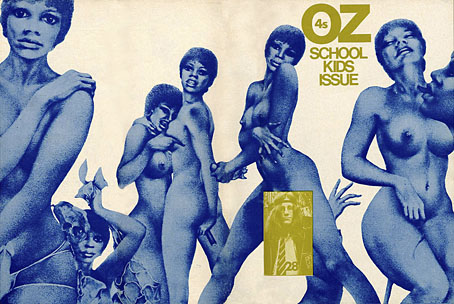

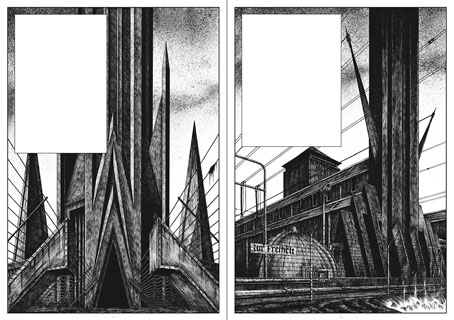

Farewell to the artist I used to refer to as my partner in art-crime. We weren’t really criminals but in the 1990s we’d both seen our published works for Savoy Books condemned as obscene in British courts of law, a farcical set of circumstances looking back, although it all seemed serious enough while it was happening. Kris and I began working for Savoy in the late 1980s, during which time our creative confederacy might be characterised as familiarity at a distance. He lived in Liverpool, and generally remained there, while the rest of us were in Manchester, so I saw his drawings much more than I saw him in person. I don’t think I ever met him more than 10 times in 30 years, yet his art was as familiar as my own, especially when I was being called upon to add backgrounds to some of his figures. I even ended up making a font based on the lettering he used in his comic strips in order to standardise the captions in the later books.

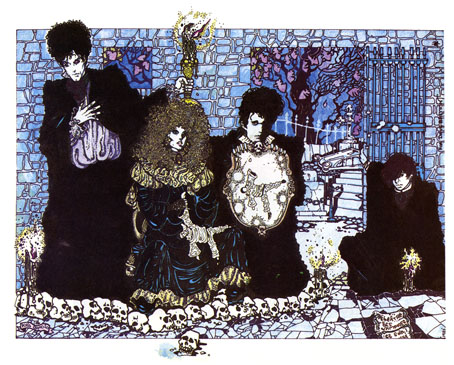

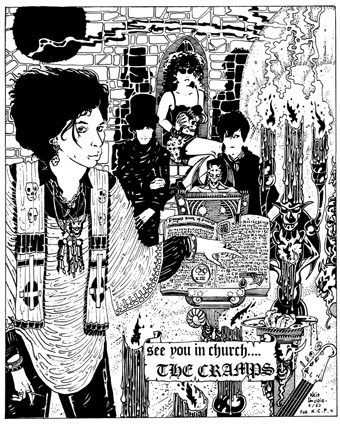

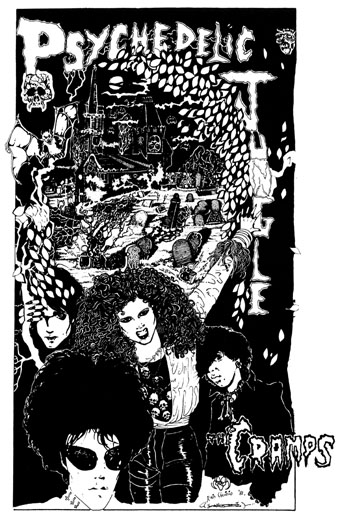

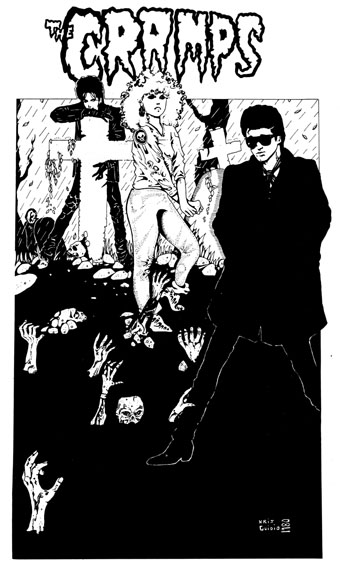

Kris and I shared a symbiotic relationship with writer David Britton, who pushed the pair of us to take our art into places we might otherwise have avoided, while we opened up artistic possibilities for Dave’s characters and the settings they occupied. We were an ideal team in this respect, each of us having strengths in different areas that suited the titles on which we worked. I brought a greater sense of realism to the Lord Horror comics, while Kris developed a hitherto unexplored flair for satire and caricature in the Meng & Ecker series. Kris was a natural cartoonist, as well as a natural humorist to a degree you wouldn’t have predicted looking at his early strips and illustrations featuring The Cramps.

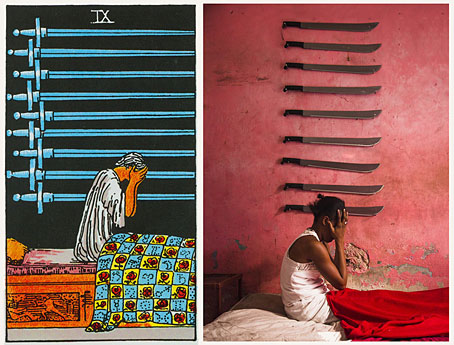

The Meng & Ecker comics provoked the ire of the authorities, thanks in part to Dave’s frequent digs at the Greater Manchester Police, but there was a lot more to Kris’s art than outrage, a quality which is always easy to generate if you push the right buttons. His Cramps strips are gems of that minor form, the rock’n’roll comic, while his later illustrations for the La Squab character had a lightness of touch that suited Dave’s conception of a world where fairy tales and childhood fantasies collide with adult themes and sensibilities. Kris’s art was analogue to the last (I don’t think he ever owned a computer), drawn with whatever pens he had to hand; watercolour-hued, and fuelled by endless cigarettes. Kris in person was generous, witty, and erudite in the autodidactic manner common to all at Savoy. Remote or not, we’ll miss him here.

Further reading:

• Sinister Legends (1988)

• The Adventures of Meng & Ecker (1997)

• Fuck Off and Die (2005)

• La Squab: The Black Rose of Auschwitz (2012)