Art by Tessa Farmer.

• An exhibition of Tessa Farmer’s art is running at Viktor Wynd Fine Art, London, until October 30th. On Saturday, October 1st, Strange Attractor hosts Good Neighbours: Faeries, Folklore and the Art of Tessa Farmer also at Viktor Wynd.

• Unearthing The Psychedelic Harp: “David Moats talks to harpist and songwriter Serafina Steer about her work with John Foxx and Patrick Wolf, being classically trained, the difficulties of doing live soundtracks and psychedelia.”

• And speaking of psychedelia, Arkhonia is still blogging up a storm here, here and here about the lost Beach Boys album, Smile, the farthest Brian and co. ventured into the tripped-out weirdness of 1967. The complete original recordings will finally be released in November.

• “‘We’ve arrived at a level of commodification that may have negated the concept of counterculture,’ Gibson says in the Paris Review.” William Gibson profiled by Thomas Jones.

One of the qualities I always stress when talking about this design work influenced by Surrealism is its enormous boldness and creative freedom, which is something of a paradox in many cases, since the Czech and Polish designs were created under communist regimes. So, while Uncanny documents a significant current in the history of 20th-century visual culture, the show also has a polemical intention aimed, quite deliberately, at our circumstances now. Students who encounter these images in lectures sometimes feel constrained by their conception of what they — or their teachers — regard as acceptable in today’s marketplace. At times, this has struck me as being a form of insidious self-censorship. (more)

Rick Poynor: Jan Svankmajer and the Graphic Uncanny.

• The exhibition curated by Mr Poynor last year, Uncanny: Surrealism and Graphic Design, is now showing at the Kunsthal in Rotterdam until early December. Related: MizEnScen’s somber, surrealist collages.

• Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates (1921) at Golden Age Comic Book Stories, the Urtext of buccaneer imagery.

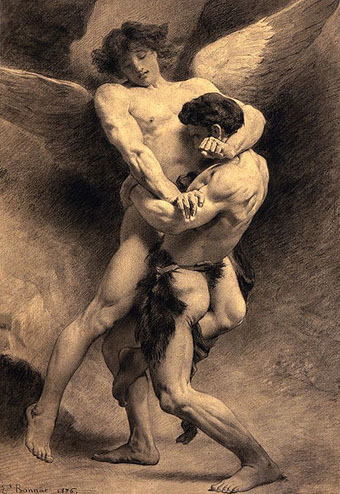

Another of those homoerotic religious pictures: Jacob Wrestling with the Angel (1876) by Léon Bonnat. Via Babylon Baroque.

• Celebrating the 250th anniversary of Laurence Sterne’s marbled page: Emblem of My Work.

• John Martin’s Pompeii painting finally restored after 1928 Tate flood damage.

• The Spectral Dimension: “where the paranormal and popular culture collide”.

• The Writing of Stones (1970) by Roger Caillois at 50 Watts.

• Mercury Arc Rectifiers.

• When silliness was an avant garde strategy: video from 1974 of Brian Eno performing China My China and (in better quality) The Seven Deadly Finns. (Go here for lyrics of the latter.)