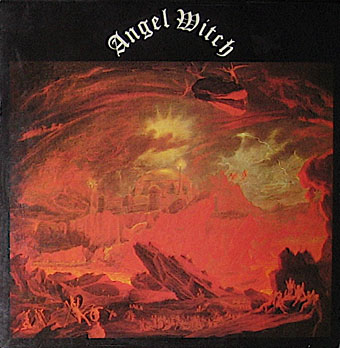

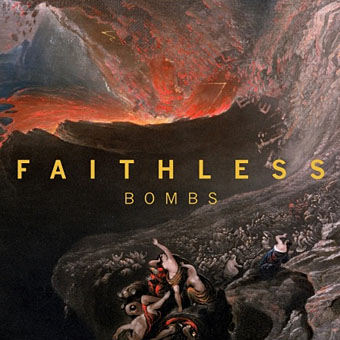

The Great Day of His Wrath (1851) by John Martin.

I’ve written on a couple of occasions about having been a precocious youth when it came to art appreciation. My first visit to the Tate Gallery (now Tate Britain) when I was 13 was of my own volition during one of our annual school visits to London. I wanted to see Modern Art (capital M and capital A), and especially my favourite Surrealist and Pop artists. Those works were present, of course, and it was a thrill to discover artists I hadn’t heard of such as Brâncusi and Moholy-Nagy, but the greatest shock came in the room reserved for the enormous canvases filled with apocalyptic scenes by Francis Danby and John Martin.

The Last Judgement (1853) by John Martin.

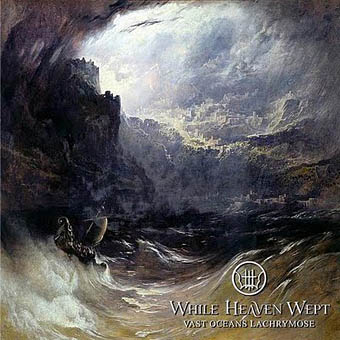

Some of these paintings have become more visible over the years, especially Martin’s startling chef-d’oeuvre, The Great Day of His Wrath, which has found a new lease of life decorating various music releases. Yet for a long time these works were never seen in art histories, being dismissed as a kind of religious kitsch, interesting perhaps for their Romantic connections (he also depicted scenes from Milton and Byron) but with Martin regarded as deeply inferior compared to his contemporary JMW Turner. If you only look at painting as being about the surface of the canvas then Martin is inferior to Turner whose nebulous works contain the seeds of Impressionism and much 20th century art. But there’s more to art than the surface. What I saw was an astonishing audacity—this artist had dared to paint the end of the world!—and three deeply strange paintings, two of which feature deliberately confused perspectives which are almost Surrealist in their effect and quite unlike any other work produced in the 19th century.

The Plains of Heaven (1851) by John Martin.

Well things change, not least critical opinion, and with the emergence in recent years of (for want of a better term) Pop Surrealism, and also the current vogue for crappy disaster movies and apocalyptic chatter, Martin’s paintings have been deemed interesting enough to warrant an exhibition at the Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle, which has been the permanent home of other Martin works for many years. The show will run there until June then travel to Sheffield (where I may pay it a visit) and Tate Britain. Of note for Martin enthusiasts will be the emergence from a private collection of the vast and lurid Belshazzar’s Feast, the painting which inspired some of the set designs in DW Griffith’s Intolerance. I once read that if the insanely huge banqueting hall in that picture had been a real construction it would have extended for at least a mile. Visitors to the new exhibition will be able to judge for themselves in close-up. And speaking of close-ups, Google’s Art Project has the three paintings above in their Tate collection; click the pictures for links.

Belshazzar’s Feast (1820) by John Martin.

• Derided painter John Martin makes a dramatic comeback

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Darkness visible

• Death from above

• The apocalyptic art of Francis Danby

![]()