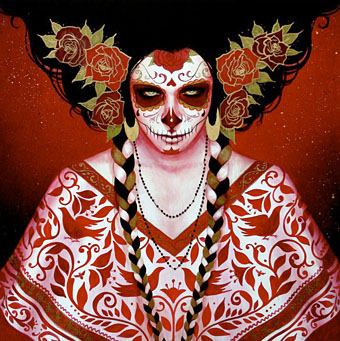

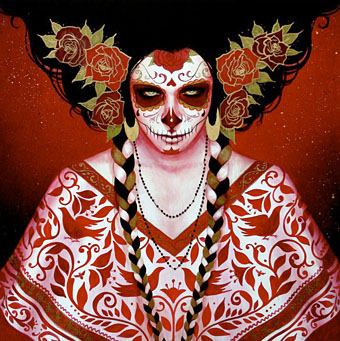

Red Quechquemitls (2010) by Sylvia Ji.

• The Blackout Mix, a pay-what-thou-wilt 49-minute mixtape, “specially designed to accompany (or simulate) a human-plant interaction”. Art by Arik Roper, music selection by Jay Babcock.

• An ode to the many evolved virtues of human semen: “the penis is capable of dispensing a sort of natural Prozac” says Jesse Bering.

• The new John Foxx CD & DVD release, D.N.A., has a Jonathan Barnbrook cover, a new collaboration with Harold Budd and a disc of short films.

• “I have been copying Margaret Hamilton my whole life, and I am proud to admit it. The Wicked Witch of the West, the jolie laide heroine of every bad little boy’s and girl’s dream of notoriety and style, whose twelve minutes of screen time in The Wizard of Oz can never be topped … I’m a big butch-lesbian hag. I love the ones with chips on their shoulders and heavy attitude. They’re my real favorites.” John Waters always gives great interviews.

• Listen to a track from the forthcoming Brian Eno album while you’re reading Kristine McKenna’s interview with the man himself at Arthur mag. Includes an appreciation by Alan Moore.

Atropa Bella Donna (2009) by Sylvia Ji.

• Steven Severin is touring the UK this month, performing a live accompaniment to screenings of Jean Cocteau’s The Blood of a Poet. He’s at the Tyneside Cinema this Tuesday. Other dates can be found on his website.

• “I know it’s a very emotive subject and you’re either for it or against it but for a jobbing self-employed musician such as me – bootlegging (CD copying) is just killing us.” Finding The Spaces Between: musician Chris Carter (Throbbing Gristle, Chris & Cosey, et al) interviewed.

• Mile End Pugatorio (1991), a one-minute film-poem by Guy Sherwin and Martin Doyle. Related: four one-minute movies by The Residents.

• Gijs Van Vaerenbergh installed an Upside Dome at the St. Michiel Church in Leuven, Belgium.

• Sidney Sime illustrates Lord Dunsany at Golden Age Comic Book Stories.

• Europe according to gay men. There’s more at Mapping Stereotypes.

• There’s never a dull moment in the High Desert.

• Generative art by Leonardo Solas.