Down to the Cellar.

“Black cats are our unconscious,” says Jan Svankmajer in an interview with Sarah Metcalf for Phosphor, the journal of the Leeds Surrealist Group. I’ve spent the past few weeks working my way through Svankmajer’s cinematic oeuvre where black cats were very much in evidence, although for a director who describes himself as a “militant Surrealist” there are fewer than you might imagine.

Jabberwocky.

The first feline appearance is in Jabberwocky (1973), a difficult film for animal-lovers when almost all the cat’s appearances seem to have involved throwing the unwilling animal into a wall of building blocks. Each “leap” that the cat makes through the wall interrupts the progress of an animated line being drawn through a maze; when the line finally escapes the maze, childhood is over. Our final view of the cat is of it struggling to escape the confines of a small cage: the unconscious tamed by adulthood.

Down to the Cellar.

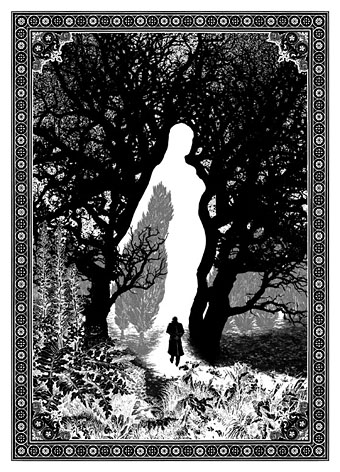

The black cat in Down to the Cellar is not only the most prominent feline in all of Svankmajer’s films, it’s also carries the most symbolic weight in a drama replete with Freudian anxiety. The cat guards the entrance to the subterranean dark where its growth in size corresponds to the mounting fears of a small girl sent by a parent to collect potatoes.

Faust.

The cat seen at the beginning of Faust (1994) appears very briefly but nothing is accidental in Svankmajer’s cinema. Two separate shots show the cat in the window watching Faust on his way to meet Mephistopheles. As with Down to the Cellar, the cat oversees the threshold to another world, in this case the doorway to a labyrinthine building filled with malevolent puppets and the temptations they offer. The cat may also be the traditional symbol of ill fortune. Faust at this point in the story still has the option to turn back but he goes on to meet his fate. (I think there may also be another cat later in the film but I was too lazy to go searching for it. Sorry.)

Little Otik.

The cat that appears in the early scenes of Little Otik (2000) is a child substitute for a childless couple, its status reinforced by the scene of Bozena holding the animal like a baby. The arrival of the monstrous Otik usurps the cat’s position as the family favourite. Consequences ensue.

Svankmajer’s later features are catless. Insects (2018) is more concerned with arthropods and their human equivalents, while Surviving Life (2010) spends so much time inside the unconscious of its protagonist it doesn’t require a symbol. Lunacy (2005), on the other hand, is a combination of a story by Edgar Allan Poe—The System of Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether—and the philosophical views of the Marquis de Sade. Svankmajer had already adapted two of Poe’s stories prior to this but The Black Cat wasn’t among them. Given the cruelties in Poe’s story and many of Svankmajer’s films, Lunacy in particular, this may be just as well.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Jan Svankmajer: The Animator of Prague

• Lynch dogs

• Jan Svankmajer, Director

• Don Juan, a film by Jan Svankmajer

• The Pendulum, the Pit and Hope

• Two sides of Liska