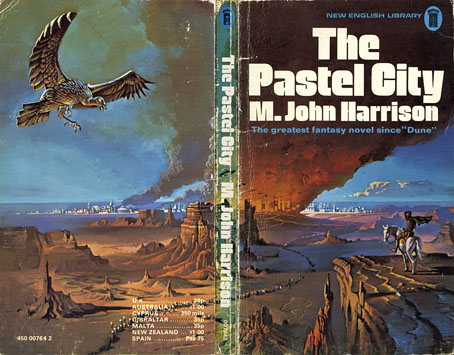

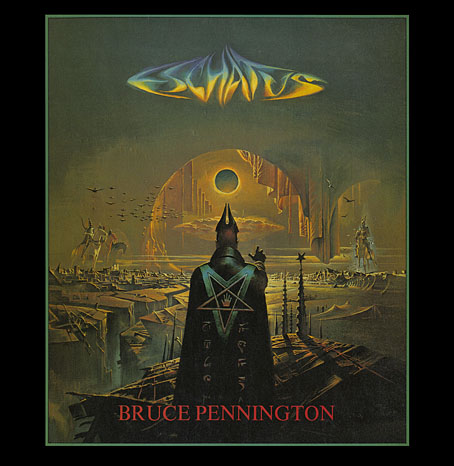

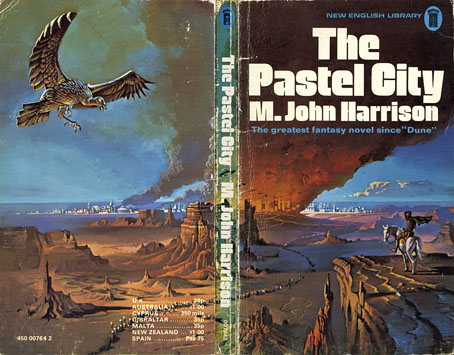

The Pastel City (New English Library, 1971). Illustration by Bruce Pennington.

There are writers’ writers, of course, and M. John Harrison is one of those. He moves elegantly, passionately, from genre to genre, his prose lucent and wise, his stories published as sf or as fantasy, as horror or as mainstream fiction. […] His prose is deceptively simple, each word considered and placed where it can sink deepest and do the most damage.

Neil Gaiman in the introduction to the Bantam/Spectra edition of Viriconium (2005)

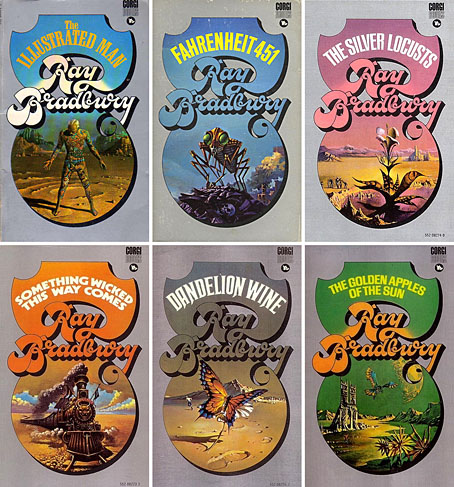

This is a lengthy post of potentially minority interest for which I make no apologies. It’s often been a function of the writing here to think aloud while communicating an enthusiasm; as enthusiasms go this one runs deeper than usual. I love these books indecently. If they were people I’d want to sleep with them even though doing so might mean contracting some debilitating illness. When you’re employed as a book designer and illustrator it’s impossible to avoid taking a professional interest in the packaging of your favourite books. M. John Harrison‘s Viriconium books—three novels and a collection of short stories—present challenges that the illustrators and art directors of the past have invariably failed to meet. This post looks at prior cover designs while a subsequent post will suggest some solutions to the challenges. But first it’s necessary to say something about Viriconium itself.

In the distant future of the Earth, when the human race has flourished then lapsed into a state of terminal decay, only one city of note remains: Viriconium, the Pastel City, surrounded by the wastes and fens of a ruined world. Or so we’re told in the first book of a series which begins as outright fantasy and moves by an astonishing feat of authorial dexterity closer to our world and our time. (A shorthand description might describe a series that starts out reading like Jack Vance and ends up closer to Bruno Schulz.) It becomes apparent that Viriconium stands for all the cities that have ever been, and with its avenues, rues and strasses often seems to be a composite of them all. Aside from the unspecified future its fixture in time is indeterminate: one story may concern events which are in the distant past of another while the streets and quarters never remain anchored enough for any kind of map to be drawn. Areas of continuity rise like towers from a sea of vapour. Even the city’s name slips its mooring: the origin is Viroconium Cornoviorum, a Roman town in Shropshire, and Viroconium, a poem by Mary Webb. In the later books we’re told the city is also called Uriconium or Vriko but whether these variants lie in the past or future of Viriconium is unclear. The indeterminacy was deliberate, a riposte to what Harrison calls “fauxthenticity”, and the tendency of genre readers to reduce the subtleties of fiction to the schematics of role-playing games, spaceship diagrams and books with titles like The Science of Middle-Earth. It’s this indeterminacy and a refusal to offer neat resolutions (or that awful term “closure”) that no doubt explains why Harrison’s books often seem to attract more praise than actual readers.

The most remarkable aspect of the books presents the greatest problems in design terms. In the fourteen years that Harrison worked on his series he used its mutable qualities to pull the entire project to pieces without actually destroying it or turning the whole thing into a self-regarding postmodern game. The early books critique the lazy assumptions of the fantasy genre while the later books recast the earlier stories as myths or half-remembered dreams. The first two books may use the apparatus of the fantasy genre but that doesn’t mean the tired imagery of fantasy illustration necessarily suits their covers. The very last story, A Young Man’s Journey to Viriconium, is set in the north of England in our own time. Changing the name Viriconium to London throughout the text, which Harrison has done when the story has been published elsewhere, dissolves the remaining genre trappings. The process is akin to watching those Buddhist monks who construct elaborate mandalas of coloured sand only to sweep them away when the work is finished. All this makes the Viriconium books unique, it’s one of many reasons why I hold them in such high regard and it’s also why they frequently irritate those who want simpler fare. The problem of appealing to a reactionary readership may explain why many of the following covers have failed to honour the content of the books.

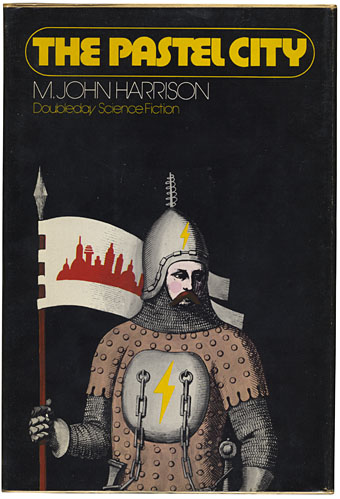

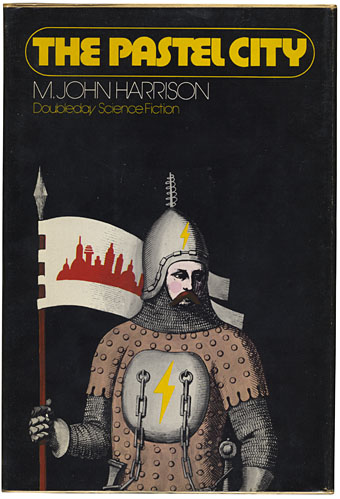

The Pastel City (Doubleday, 1972) Illustration by Wendell Minor.

Dustjacket summaries do none of the books any favours but for the unacquainted they help give a flavour of each volume. They also show how the presentation gradually shifts emphasis. Here’s the Doubleday edition:

An intriguing fantasy in which past and future blend uniquely on an Earth far different from any known to man.

There, in the Empire of Viriconium, a world of chivalry, of magic and strange powers, two Queens clash in bloody warfare for control of the Pastel City and all of its domains. The armies of the defender, Queen Methvet, are led by Lord tegeus-Cromis and the rest of a legendary band of knights, while their attackers are the vicious and cunning Northmen who serve the rival Queen Moidart.

More is involved than a struggle for a throne however, for in their lust for victory the forces of Queen Moidart have unleashed creatures from Earth’s dim past whose terrible potential they little realize until too late. And as Lord Cromis and the rest of his band seek to meet the challenge of these nightmare apparitions, their quest leads them on a perilous journey across many weird lands to a deadly climax in a buried city where a solution is revealed that is as old as time itself.

It’s apposite that a series about an indeterminate city begins with some confusion evident from the outset. The Pastel City in its first UK printing was described on the cover as a fantasy yet compared to Dune which is generally regarded as science fiction; the Doubleday edition is labelled science fiction yet the cover illustration shows a mailed and armoured warrior; the narrative is situated somewhere between the genres in what used to be called science fantasy. While the story concerns the distant future many of the props are the familiar material of heroic fantasy: horses, swords, feuding queens, an axe-wielding dwarf. What technology remains is either defunct or barely functioning. The ruin and decay of Harrison’s world is part of the pleasure, as is the vacillating and ambivalent nature of the characters, a quality which increases as the series develops. None of the publishers dare to reflect this ambivalence in the cover art. Unaware readers would be led to believe from subsequent editions that these books contain the determined and super-efficient heroes they’d find in other books. Compared to what follows the first two covers aren’t so bad; Bruce Pennington gives us one of his flying saucer apocalypses while Wendell Minor’s avoidance of a genre scene is an approach that might have been deployed a lot more often later on.

Continue reading “Covering Viriconium”