The Titan’s Goblet (1833).

Thomas Cole’s Titan’s Goblet isn’t featured at the Google Art Project, unfortunately, but the following paintings are, and all benefit from being able to explore their details. Cole’s colossal vessel predates Surrealism by a century, and is one of many paintings which always has me mentally labelling him as the American John Martin (1789–1854). Having thought of him for years as an American artist–not least because he founded the Hudson River School–it’s a surprise to learn he was born in Bolton, a town not far from Manchester, with his parents emigrating to the US when he was 17. John Martin also grew up in the north of England so there’s another similarity, although the more important comparison concerns their use of painting to convey the spectacularly vast and unreal scenes common to the imaginative side of Romantic art. The Titan’s Goblet is unusual in not having any particular symbolic or moral significance, unlike the pictures below, it’s Magritte-like in its careful depiction of the impossible. The Subsiding of the Waters of the Deluge, on the other hand, could be exhibited beside Francis Danby’s The Deluge (1840) for a “before and after” effect. Like Martin, Cole enjoyed painting architecture of an exaggerated scale. The Architect’s Dream features an Egyptian temple of stupendous size, while the pyramid looming in the background is closer to William Hope Hodgson’s seven-mile-high Last Redoubt than any structure on the Nile plain.

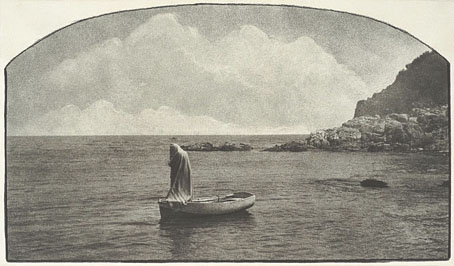

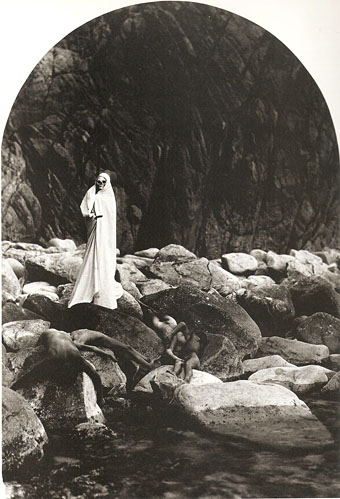

Of equal interest are Cole’s two well-known series: The Course of Empire (1833–36) and The Voyage of Life (1842), both of which I’d love to see at Art Project size.

Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (1828).

The Subsiding of the Waters of the Deluge (1829).

The Architect’s Dream (1840).

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The fantastic art archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• John Martin’s musical afterlife

• Albert Bierstadt in Yosemite

• Danby’s Deluge

• John Martin: Heaven & Hell

• Darkness visible

• Two American paintings

• The apocalyptic art of Francis Danby