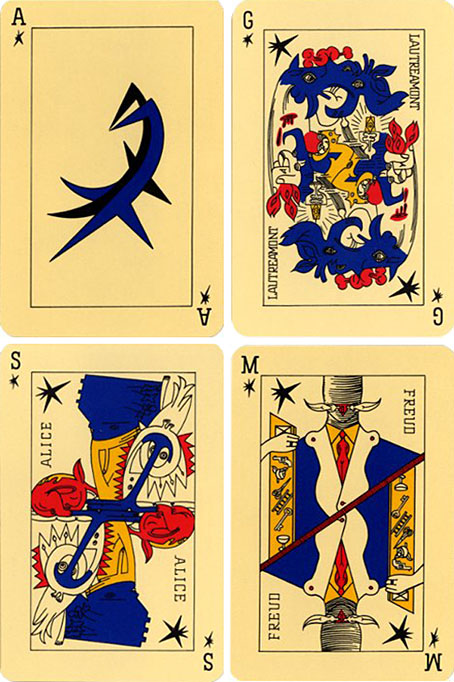

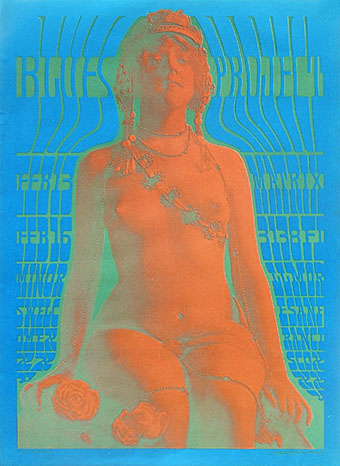

La Menace (1994).

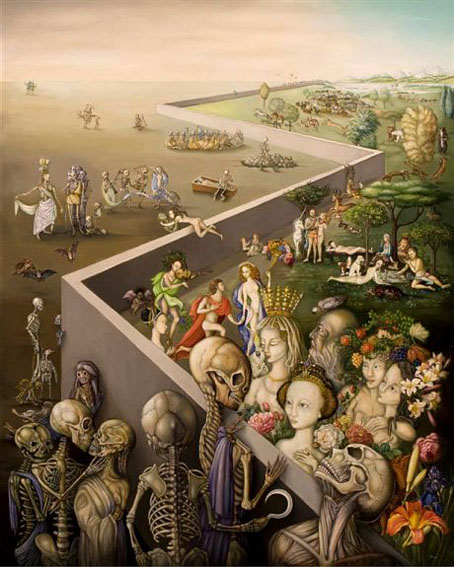

Two paintings by Princess Marsi Paribatra, a member of the royal family of Thailand who lists Dalí, Arcimboldo and Titian among her artistic influences. If it seems surprising that a princess should not only be an accomplished painter but also be possessed of a distinctly vivid imagination we might ask why this is the case. There’s no reason why a member of a royal family shouldn’t be as good a painter as anyone else although it’s the case that here in Britain our views of royalty are inevitably tainted by the uninspiring members of the current House of Windsor. Prince Charles in particular is a singularly dreary and frequently philistine figure, and also a painter whose daubs would never have received any attention at all were it not for his being born into the right family.

This hasn’t always been the case. It used to be that being an aristocrat gave you the free time and the wealth to indulge no end of manias and eccentricities. The British Isles are littered with architectural follies of various kinds built to appease the whims of rich landowners; William Beckford (1760–1844) is renowned for having written the Gothic melodrama Vathek and also for having built the lavish (and unfortunately short-lived) pile of Fonthill Abbey. In the 20th century we had Edward James (1907–1984), a lifelong champion of Surrealism who spent much of his later life building Las Pozas in the Mexican jungle at Xilitla, a concrete fantasia which looks like something dreamed up by Antonio Gaudí and JG Ballard. James collected the work of Leonora Carrington and Dorothea Tanning and I’d imagine him being equally entranced by some of Marsi Paribatra’s paintings. The recurrence of skeletal figures in her work invokes the Mexican Day of the Dead traditions which always excited the Surrealists.

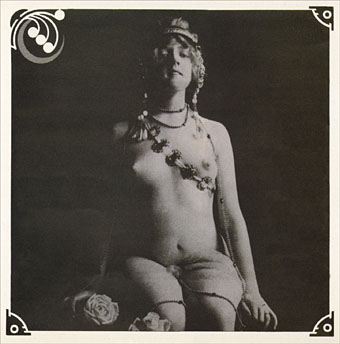

No title or date available.

Dali House has more about Marsi Paribatra’s life and art while further examples of her paintings can be found here and here. Thanks again to Monsieur Thombeau for pointing the way!

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The fantastic art archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Angels of Anarchy: Women Artists and Surrealism

• Return to Las Pozas

• The art of Leonor Fini, 1907–1996

• Surrealist women

• Las Pozas and Edward James