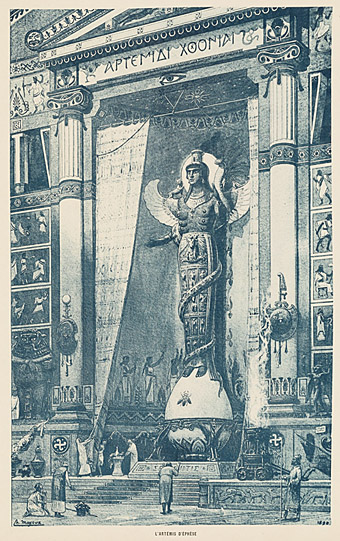

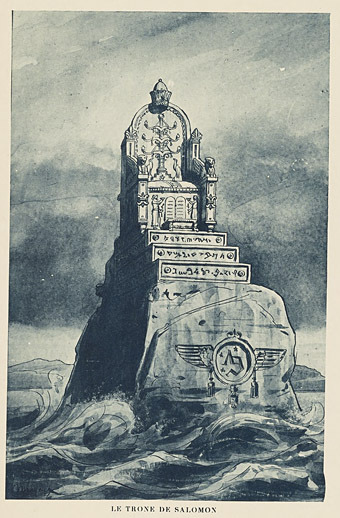

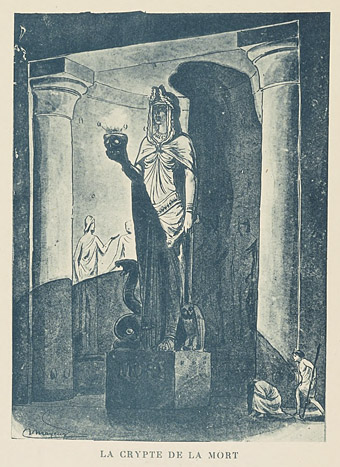

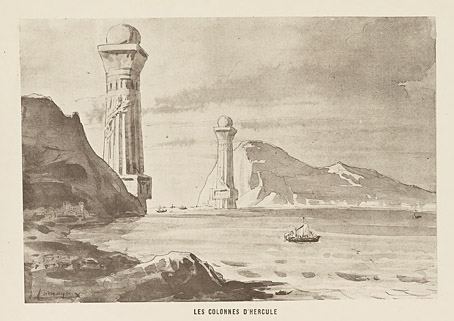

An entire book of architectural caprices is just the thing I like to see, so it’s a shame that most of the examples in Fantaisies Architecturales (1890) by Henri Mayeux are little more than sketches. Mayeux was an architect and a professor of decorative arts whose previous book had been a guide to the composition of decoration and its historical use. Fantaisies Architecturales applies a similar approach to architectural styles, offering a variety of historical pastiches as well as suggestions suited to stage designs and more contemporary buildings.

Mayeux’s inventiveness is considerable but he shares with many of the architects of 19th-century expositions a reluctance or inability to imagine anything that breaks with the styles of the past. Étienne-Louis Boullée’s colossal plan for a cenotaph for Isaac Newton (proposed in 1784) remains astonishing because its design is so unprecedented. The construction of the vast internal sphere may have exceeded the engineering limits of the time but the unadorned abstraction of the design is closer to the architecture of the 20th century than anything from the 19th. The Eiffel Tower had been built a couple of years before Mayeux’s book was published but it wasn’t until the Exposition Universelle of 1900 that Paris saw any other buildings that could complement its architectural novelty.

Continue reading “Fantaisies Architecturales by Henri Mayeux”