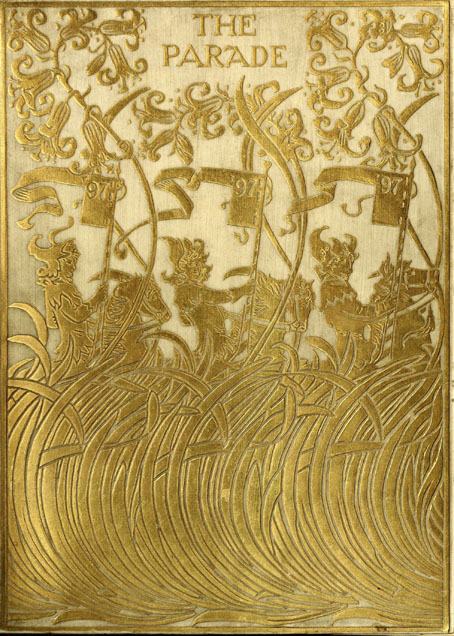

Design by Paul Woodroffe.

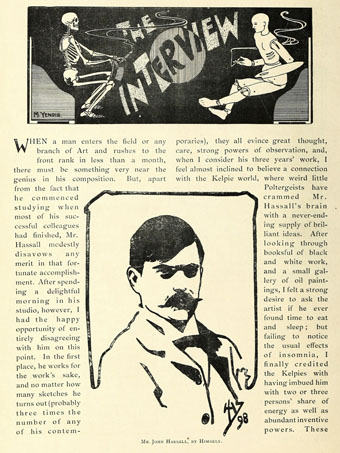

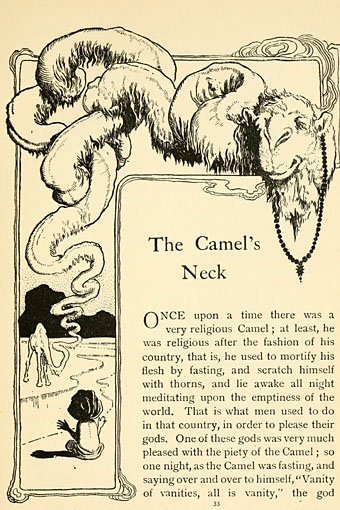

The Parade, subtitled An Illustrated Gift Book for Boys and Girls, is something that children with wealthy parents or relatives might have received as a Christmas present in December 1897. The contents are an unusual mix of fairy tales, frivolous seasonal fare—A Christmas Mummery, complete with songs and music—and adventure stories set in other parts of the world. The collection was edited by Gleeson White, an art critic whose former position as editor of The Studio magazine explains the very Studio-friendly choice of illustrators.

The design on the title page is a curious piece by Aubrey Beardsley, one with less authority than the most of the other drawings he was producing in his penultimate year. Those dots filling out the arabesque plant forms are the kinds of things that amateurs do when they’re uncertain about whether or not to decorate a design. The tendril which terminates in a tasselled confection is, however, a typical example of the artist’s bizarre invention, the kind of caprice that used to infuriate the critics who disliked his work. Beardsley’s career had been launched four years earlier with a profile in The Studio, but by 1897 he was often struggling for money after being fired from The Yellow Book in the wake of the Oscar Wilde scandal. Gleeson White is to be commended for supporting him at a time when many others refused to do so.

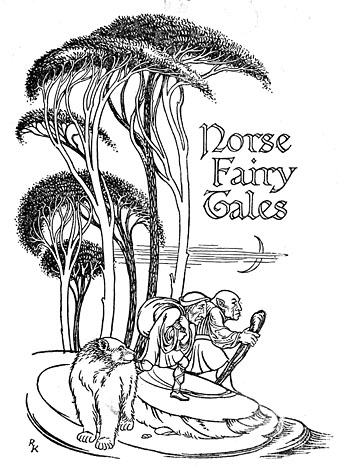

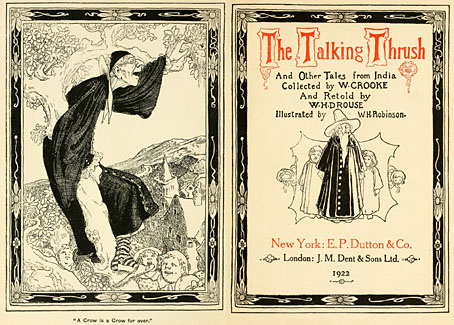

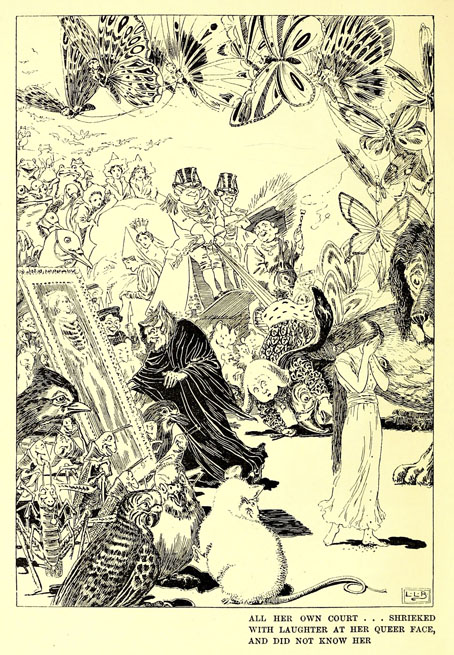

L. Leslie Brooke.

Elsewhere in The Parade there are contributions both written and pictorial from Beardsley’s friend, Max Beerbohm; also a story by Richard Burton, a writer you wouldn’t usually expect to find in a book aimed at children. The list of illustrators includes Charles Robinson, Laurence Housman and Manchester’s own Alfred Garth Jones. Beardsley didn’t draw anything else for The Parade but he’s mentioned again in a list of titles advertised in the book’s final pages as having provided a frontispiece for Baron Verdigris, “A Romance of the Reversed Direction” by one Jocelyn Quilp. The title was unfamiliar, and I wasn’t sure at first whether I’d seen the illustration, but the drawing shown below appears in two of my Beardsley books—albeit at small sizes—including the copious Brian Reade collection from 1967.

“Baron Verdigris” sounds like a minor character from Michael Moorcock’s Dancers at the End of Time trilogy, while the improbable “Jocelyn Quilp” turns out to be a nom de plume of Halliwell Sutcliffe whose book is described as a “singular novella, a curious amalgam of parodies based on a time-travelling theme“; shades of the Dancers again. It’s tempting to think that this may be the sole example of Aubrey Beardsley illustrating science fiction (or something like it)—the book is generic enough to be listed at ISFDB—but Brian Reade describes the story as “pseudo-mediaeval and facetious”, “dedicated to ‘Fin-de-Siécle-ism, the Sensational Novel, and the Conventional Drawing-Room Ballad'”. That does at least explain the peculiarities of the drawing. Maybe the Moorcock comparison is an apt one after all.

More illustrations from The Parade:

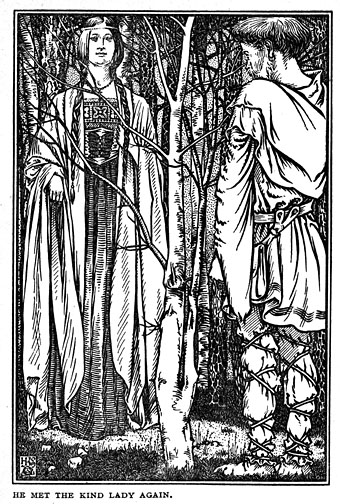

Charles Robinson.

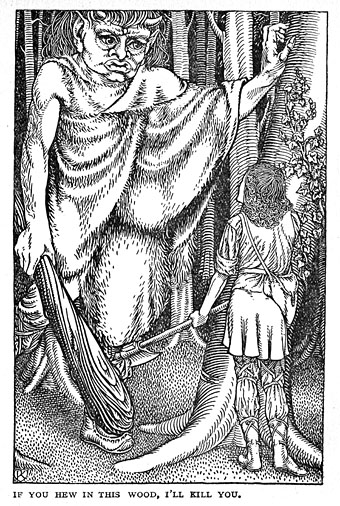

Léon V. Solon.