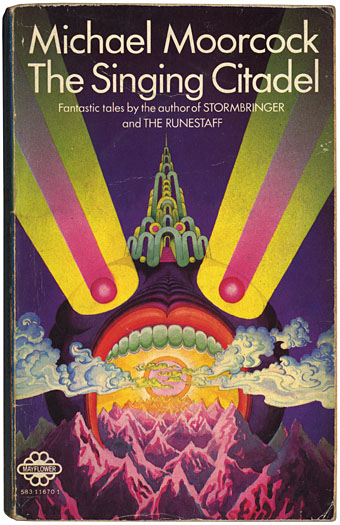

The Singing Citadel (1970).

Michael Moorcock’s Elric books are being prepared for republication by Del Rey in the US next year. I’ve assisted with some minor parts of this preparation, including sourcing pictures from Savoy’s edition of Monsieur Zenith the Albino. (Anthony Skene’s albino anti-hero is a precursor of Moorcock’s albino anti-hero.)

Discussion of the Elric books with Dave at Savoy prompted my excavation of this battered Mayflower paperback from the retired book boxes. This slim volume collected four fantasy stories: the title piece (possibly the first Elric story I read), Master of Chaos, The Greater Conqueror and To Rescue Tanelorn…. I’d forgotten about the garishly strange cover, one of many that Bob Haberfield produced for Moorcock’s books during the 1970s. Haberfield is one of a number of cover artists from that period who worked in the field for a few years before moving on or vanishing entirely. The swirling clouds derived from Tibetan Buddhist art identify this as one of his even without the credit on the back; later pictures were heavily indebted to Eastern religious art and while technically more controlled they lack this cover’s berserk intensity. Haberfield’s site has a small gallery of his splendid paintings, including a rare horror work, his wonderfully eerie cover for Dagon by HP Lovecraft.

Searching for more Haberfield covers turned up these two examples, both part of the SciFi Books Flickr pool, a cornucopia of pictures by vanished illustrators. Browsing that lot is like being back inside the In Book Exchange, Blackpool, circa 1977. The digitisation of the past continues apace at the Old-Timey Paperback Book Covers pool and the Pulp Fiction pool. Don’t go to these pages if you’re supposed to be doing something else, it’s easy to find yourself saying “just one more” an hour later.

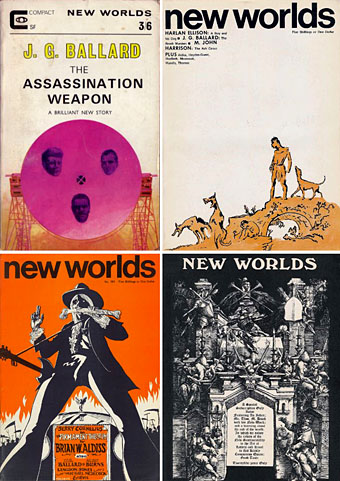

And in other Moorcock-related news, Jay alerts me today to the existence of an archive of New Worlds covers, something I’d been hoping to see for a long time. New Worlds was one of the most important magazines of the 1960s, mutating under Moorcock’s editorship from a regular science fiction title to a hothouse of literary daring and experiment. As with so many things in that decade, the peak period was from about 1966–1970 when the magazine showcased outstanding work from Moorcock himself, JG Ballard, Brian Aldiss, Harlan Ellison, Samuel Delany, M John Harrison, Norman Spinrad and a host of others. For a time it seemed that a despised genre might be turning away from rockets and robots to follow paths laid down by William Burroughs, Salvador Dalí, Jorge Luis Borges and other visionaries. We know now that Star Wars, Larry Niven and the rest swept away those hopes but you can at least go and see covers that pointed to a future (and futures) the world rejected.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The book covers archive

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Barney Bubbles: artist and designer

• 100 Years of Magazine Covers

• It’s a pulp, pulp, pulp world