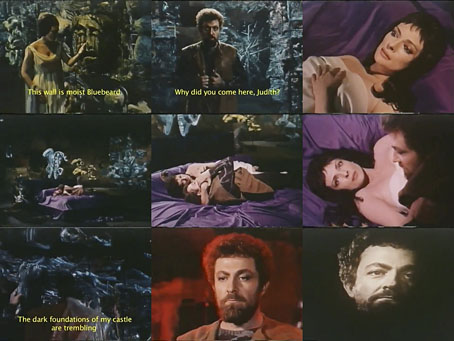

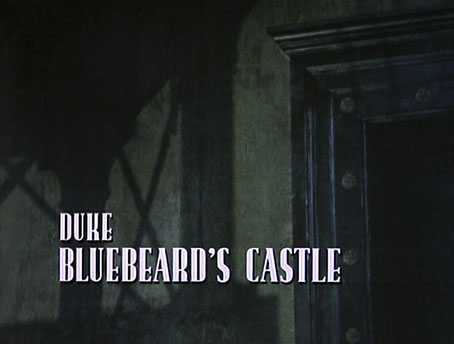

Yesterday’s post prompted me to look again for one of Michael Powell’s scarcest films, his television version of Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle made for Süddeutscher Rundfunk in 1963. Sure enough, it’s now on YouTube in a watchable copy taken from VHS tape. Herzog Blaubarts Burg (to use its German title) was made post-Peeping Tom when the director’s career was at its lowest ebb, and while the production values don’t match those he’d been used to in the 1940s he was no doubt happy to be working at all after being vilified by the UK press. Norman Foster is Bluebeard and Ana Raquel Satre plays Judith, with the libretto being a German translation with English subtitles. I ought to note here that I’ve not read the second volume of Powell’s biography (mea culpa) so the only information I have about this comes from Ian Christie’s Arrows of Desire: The Films of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger (1985). Christie doesn’t have much to say about it other than pointing out that Norman Foster financed the film, and that it’s seldom been screened in Britain: IMDB has the first UK screening as 1978, just prior to the time when Powell and Pressburger began to receive to some belated recognition.

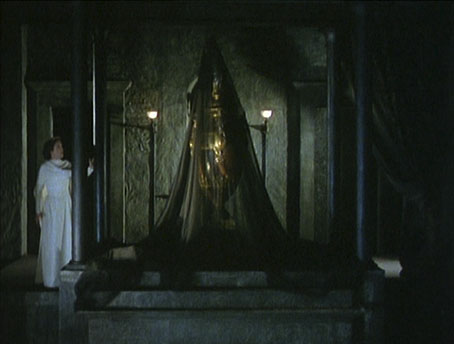

The YouTube copy suffers in the sound department by being a muffled mono transmission but it’s the visuals which will be of most interest to Powell aficionados. Powell & Pressburger’s regular production designer Hein Heckroth created the multi-coloured labyrinth which serves as the castle. The overall effect is stagey but contains some unique details, such as the rune-etched standing stones shown at the opening and close, and also some painted moments similar to those seen during the celebrated dance sequence in The Red Shoes (1948). Powell’s staging is much more vivid and artificial than Leslie Megahey’s 1988 adaptation whose Gothic gloom remains a personal favourite. Despite its shortcomings, when compared to the other Powell films that came after—the two Australian features, the Children’s Film Foundation commission which reunited him with Pressburger—this is far closer to the greatest works of the Archers era, and provides a more satisfying career coda for the man who directed The Red Shoes and The Tales of Hoffmann.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Joseph Southall’s Bluebeard

• Leslie Megahey’s Bluebeard

• Powell’s Bluebeard

• The Tale of Giulietta