A 1933 poster for the second of Fritz Lang’s Mabuse films.

• Good news for those who missed the original run (from 2002–2013), Arthur Magazine is now available for the first time as a complete set of free PDFs. I was laterally involved with the magazine from the outset, mostly as a remote supporter, but I also did several covers and interior illustrations for the early issues.

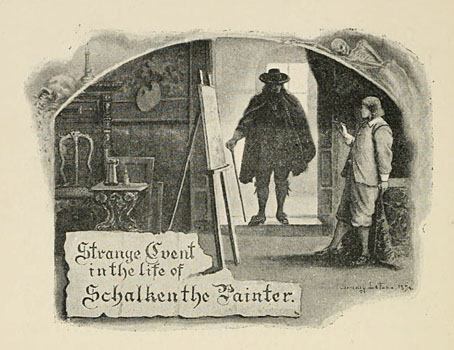

• Among the new titles at Standard Ebooks, the home of free, high-quality, public-domain texts: Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler by Norbert Jacques (translated by Lilian A. Clare); and two books by J. Sheridan Le Fanu: Short Fiction, and a novella, The Room in the Dragon Volant.

• New music: Spilla by Ensemble Nist-Nah; and Sea-swallowed Wands by Jolanda Moletta and Karen Vogt.

With his compulsions for systems and architecture, his command of shadows and symbolism-imbued sets and props, Lang is never less than arresting. Yet few of the films make complete statements; Lang’s art, in this period, is seemingly as much a fugitive as are his archetypal characters. That is, until the moment that his long journey to the direct subject matter and cultural framework of the 1950s United States, addressed in the terms and by the means available to him in Hollywood, abruptly comes to superb fruition with The Big Heat.

Jonathan Lethem on Fritz Lang in Hollywood and one of the greatest noir pictures of the 1950s

• This week in the Bumper Book of Magic: an enthusiastic review at The Joey Zone. My thanks to Mr Shea!

• Mixes of the week: A mix for The Wire by Nina Garcia; and Isolated Mix 133 by Pentagrams Of Discordia.

• At Colossal: David Romero’s digital recreations of Frank Lloyd Wright’s unrealised buildings.

• At Smithsonian magazine: John Last investigates the history of the Tarot.

• At Planet Paul: An interview with artist Malcolm Ashman.

• At the Daily Heller: A porno gag mag with attitude.

• Das Testaments Des Mabuse (1984) by Propaganda | (The Ninth Life Of…) Dr Mabuse (1984) by Propaganda | Abuse (Here) (1985) by Propaganda