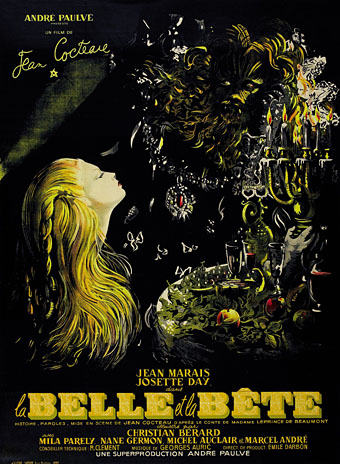

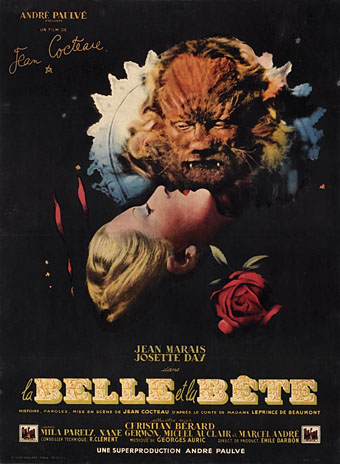

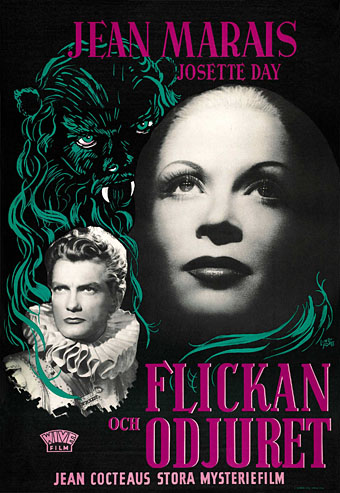

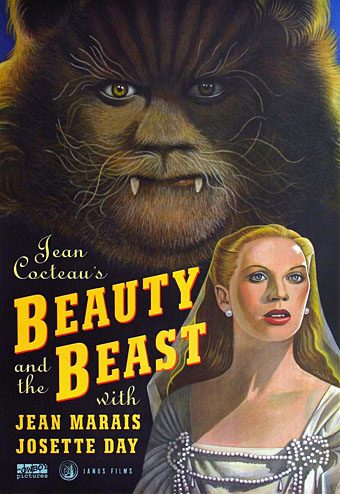

Clive’s posts last week about Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête (here, here and here) sent me back to the film, a most welcome re-viewing. This in turn had me searching for copies of the posters of which these are some of the better examples. No dates or credits, unfortunately, although the French ones above and below look as though they may have been drawn by the film’s production designer, Christian Bérard. (Update: not Bérard, they’re the work of poster artist Jean-Denis Malclès.)

The style of Bérard’s drawings, and much of the film itself, had me thinking this time round of Hein Heckroth, Michael Powell’s favourite production designer whose sketches also had a painterly style. Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes (with designs by Heckroth) appeared a couple of years after La Belle et la Bête although Powell doesn’t mention Cocteau at all in his autobiography so there’s no need to go looking for influences. Both films are based on fairy tales, of course. Powell shared Cocteau’s taste for fantasy and cinematic magic although the closest he gets to the story of Beauty and the Beast is Peeping Tom (1960), a film that contains little of either. By coincidence, Powell scholar Ian Christie calls Peeping Tom the director’s equivalent of Cocteau’s Le testament d’Orphée which was also released in 1960. But that’s a speculation for another day.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The writhing on the wall

• Le livre blanc by Jean Cocteau

• Cocteau’s sword

• Cristalophonics: searching for the Cocteau sound

• Cocteau at the Louvre des Antiquaires

• La Villa Santo Sospir by Jean Cocteau