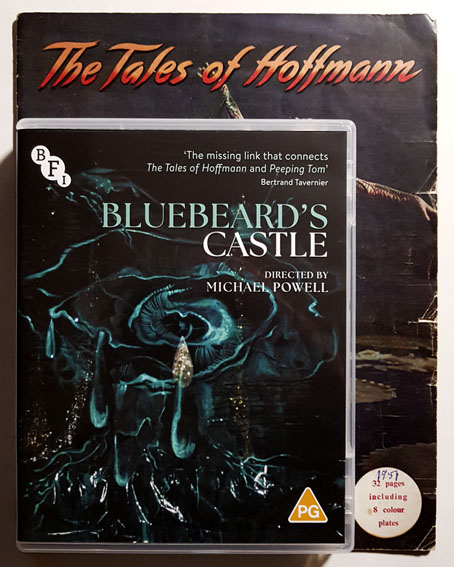

My film viewing at the weekend included a return visit to Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s opéra fantastique, The Tales of Hoffmann, followed by the new blu-ray restoration of Powell’s Bluebeard’s Castle. This is the third time I’ve written about Powell’s film of the Bartók opera, the first occasion being a “When will I get to see this?” post, the second a review of a VHS copy which had turned up on YouTube. The new release, which is the film’s debut appearance on disc, is a restoration by the BFI under the supervision of Thelma Schoonmaker and Martin Scorsese.

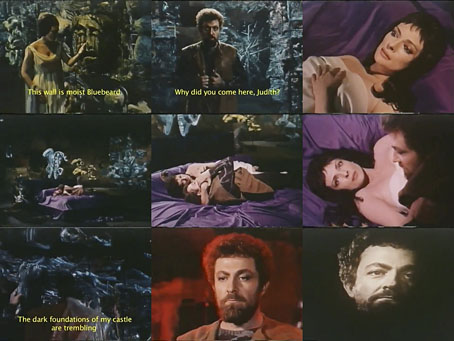

Norman Foster (Bluebeard).

Powell directed the hour-long dramatisation for the German TV channel Süddeutscher Rundfunk in 1963, at a time when his career was in the doldrums following the critical outrage provoked by the release of Peeping Tom. The production was a smaller one than he was used to but it was still shot on 35mm which has now been polished to a breathtaking degree, revealing rich shadows, deep colours and a profusion of glittering detail. (See this clip.) The audio track remains monophonic but the sound is a great improvement on the VHS version. Seeing the latter was gratifying after so long a wait but was also an underwhelming experience. The restoration proves once again how unfair it is to judge filmmakers from a low-grade copy of their work that’s been thrown onto the internet.

Ana Raquel Satre (Judith).

Bluebeard’s Castle (or Herzog Blaubarts Burg, to use the film’s German title) wasn’t a project that Powell inaugurated. Hein Heckroth, the production designer on many of Powell and Pressburger’s colour features, had been working for German TV since the late 1950s, and suggested to singer/producer Norman Foster that Powell might be interested in directing the film. The presence of Heckroth’s weirdly Expressionist designs give Bluebeard’s Castle a continuity with the extended ballet sequence in The Red Shoes and the “Giulietta” episode of The Tales of Hoffmann; all three stories share a dream-like atmosphere whose grading to nightmare is enhanced by Heckroth’s decors. I’ve often wondered whether the strangeness of some of Heckroth’s set designs, whose aesthetics extend to Dalínean Surrealism, were a factor in the frequent grumblings of distaste expressed by British critics for Powell and Pressburger’s films even before Powell made Peeping Tom. The first film that Powell worked on was The Magician in 1926, Rex Ingram’s adaptation of the Somerset Maugham novel, and a film which is at its best in its moments of visual excess. Powell’s films are valued today for their own visual excess but this quality hasn’t always been encouraged in British cinema, as Ken Russell later discovered. Favourable critics like Ian Christie often point to this as part of the “European” sensibility of Powell and Pressburger’s oeuvre, something which is present even when the subject matter is very English. Pressburger was a Hungarian emigré, while Powell met Ingram when he was living in the south of France; the production designers on all the major P&P films, Alfred Junge and Hein Heckroth, were both German, and the films themselves, especially The Red Shoes and The Tales of Hoffmann, feature a host of different nationalities. Watching Bluebeard’s Castle again I was reminded of Italian horror cinema, especially the films of Mario Bava. When you combine the artificiality of Heckroth’s sets with the Gothic story of a woman imperilled by a powerful aristocrat, plus the resemblance of Ana Raquel Satre to Barbara Steele, the whole thing assumes a very Bavaesque flavour.

On a musical level I much prefer Bartók to Offenbach, (although Offenbach’s famous Barcarolle is always worth hearing) so I’m pleased that this minor work has been treated to the same restorative care as The Tales of Hoffmann. The 1988 version of Bartók’s opera directed for the BBC by the late Leslie Megahey remains my favourite filmed Bluebeard even though it lacks Powell’s flamboyance; Megahey’s film has more gravitas, and the direction, performances and musical recording are better. But seeing Powell’s film again revealed nuances I’d missed before, like the sustained shot near the end when Judith seals her fate by asking for the key to the forbidden room. It also makes a change hearing the whole thing sung in German, a language I can understand in parts. Bluebeard’s Castle is a further example of Powell’s idea of a “composed film”, a work that would combine all the dramatic arts. (Or almost all—this one lacks dance.) As I said ten years ago, it may be minor compared to the films that he made with Emeric Pressburger but it offers a more satisfying coda to his career than his final features.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Bluebeard’s Castle, 1981

• Powell’s Bluebeard revisited

• Joseph Southall’s Bluebeard

• Leslie Megahey’s Bluebeard

• Powell’s Bluebeard

• The Tale of Giulietta