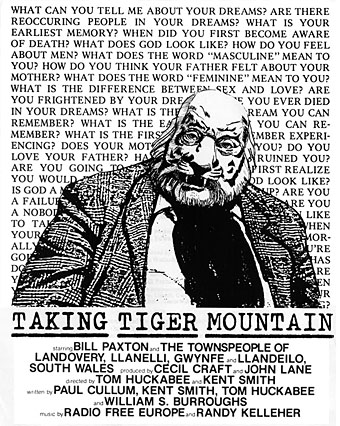

Another week, another obscure black-and-white science fiction film. I hadn’t heard of this one at all until it was announced in 2012 that co-director Tom Huckabee would be attending a rare screening in New York. The film is an oddity with a complicated history that I’m too lazy to try and condense so here’s the borrowed detail:

IMDB: In a dystopian future, Europe is unified under a totalitarian patriarchy, where each town is assigned a single economic purpose. In Brendovery, Wales the occupation is prostitution. Arriving by train from London is Billy Hampton, a young American expatriate and draft evader (Bill Paxton in his first lead role), ostensibly there to enjoy a sex-filled holiday. Unknown to him he is a time bomb assassin, programmed by a feminist terrorist cell to assassinate the local minister of prostitution.

Wikipedia: Taking Tiger Mountain is a 1983 American science fiction film directed by Tom Huckabee and Kent Smith, and starring Bill Paxton in one of his earliest on-screen acting roles. Originally conceived as an experimental art film inspired by a novel by Albert Camus’s 1942 novel The Stranger and a poem by Smith, the film was initially directed by Smith and shot in Wales. Aside from Paxton, the film’s cast is made up of townspeople from the areas in which shooting took place. It was filmed without sound, with the intention of adding dialogue in post-production. During post-production, Huckabee took over as the film’s director, abandoning Smith’s original concept and instead loosely basing the film on the 1979 novella Blade Runner (a movie) by William S. Burroughs. The film premiered on March 24, 1983. Over three decades later, Huckabee re-edited the film and released it as an alternate cut titled Taking Tiger Mountain Revisited.

Tom Huckabee: The story went through four distinct periods of creation:

1. Kent Smith’s original script, entitled Taking Tiger Mountain, written in 1974, based loosely on the John Paul Getty III’s kidnapping of 1973 and Albert Camus’ The Stranger. It was set in the casbah of Tangier, Morocco.

2. After Bill and Kent got ejected from Morocco before shooting even a foot of film, they drove to Wales, adapting the script significantly to the new location and the people and opportunities that presented themselves; but they ran out of film and money after shooting about half of their script.

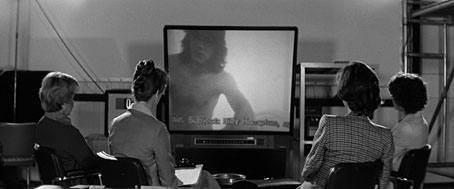

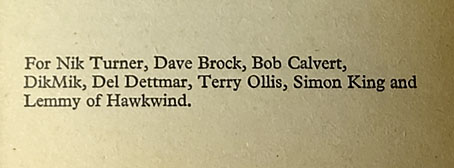

3. After I acquired the footage in 1979, I knew I couldn’t go back to Wales, so after editing their footage to about 55 minutes, I wrote a new story with a lot of help from collaborators, like Paul Cullum, Lorrie O’Shatz, and Ray Layton. I incorporated the Burroughs material and dropped the 55 minutes from Kent and Bill’s script into it. We wrote the ten-minute introductory section with the women and shot it on a sound stage in Austin, incorporating footage from another unfinished film by Kent and Bill called D’Artangan. I also built ten minutes of scenes from outtakes. In 1980, Paxton came to Austin for a few days to “loop” all of his dialogue, as no sound had been recorded in Wales. He improvised a lot of his voice-over narration, while under hypnosis. This film, called Taking Tiger Mountain, was released on 35mm in 1983 and toured the Landmark Theater chain of art cinemas.

4. In 2016 I got a small advance from Etiquette Pictures for digital distribution and decided to do a major upgrade. I cut out ten minutes and added five, including the new ending, which comes after the end credits, significantly changing the message of the film. I reworked the narrative, making it easier to follow.

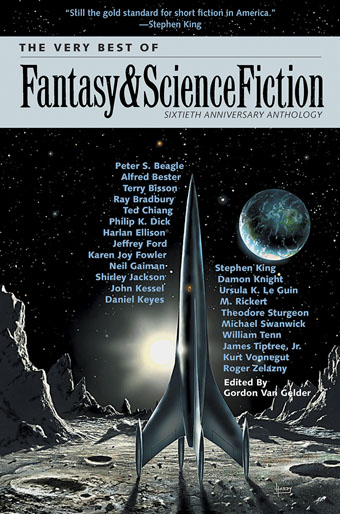

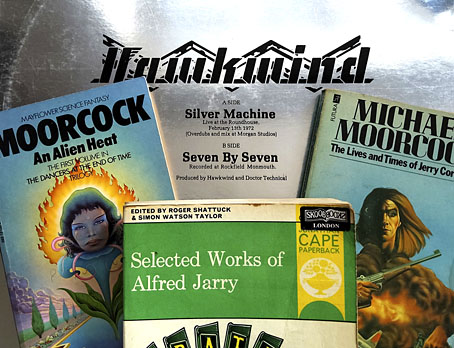

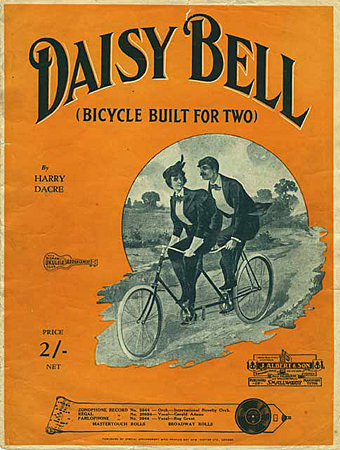

In addition to the complications of the production it’s necessary to note that the title has nothing to do with either Brian Eno’s Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), or the Chinese opera the Eno album is named after, although we do get to hear about a tiger mountain. This reflects the equally tangled history of the “Blade Runner” title, which Taking Tiger Mountain does have some connection with via William Burroughs’ Blade Runner: A Movie. This was Burroughs’ cinematic reworking of a science fiction novel by Alan E. Nourse, The Bladerunner (1974), a piece of futurism about the very American dystopia of a nightmare healthcare system. Blade Runner: A Movie followed Burroughs’ earlier screenplay/novella, The Last Words of Dutch Schultz, although the Nourse adaptation was a much more ambitious scenario with little chance of ever being filmed. No studio in the 1970s (or today, for that matter…) would have put up the money for something that’s like a wilder version of Escape from New York with added gay sex and time travel, however attractive this may sound. As is well known by now, the treatment’s title was later purloined by another film that has little else in common with anything discussed here.

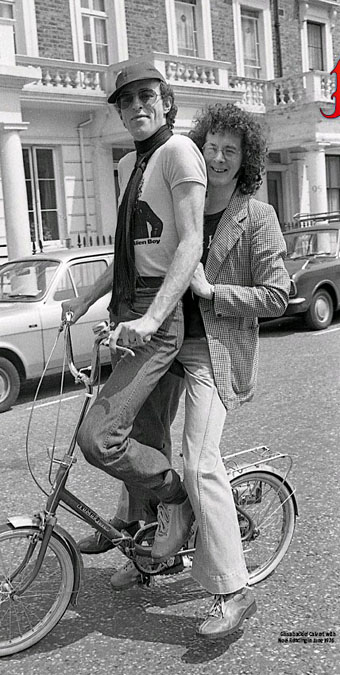

All of which means that Taking Tiger Mountain is exactly the kind of thing guaranteed to stoke my curiosity: a Burroughs-derived science-fiction film made on the cheap by Americans in south Wales, of all places. Why Wales? Because Bill Paxton had been there as a foreign exchange student. I’m not sure I would have been as interested without the disjunctive frisson of gloomy, rain-swept Wales in the mid-1970s colliding with William Burroughs. That said, the blu-ray release from Vinegar Syndrome has two things immediately in its favour: for a micro-budget production the film has excellent photography (the black-and-white stock was provided by leftovers from Bob Fosse’s Lenny); and there’s a surprising amount of unsimulated sex, something that isn’t such a big deal today but certainly was in 1974. The youthful Bill Paxton is gorgeous and exceptionally photogenic, so the film is a pleasure to watch even when little of substance is happening.