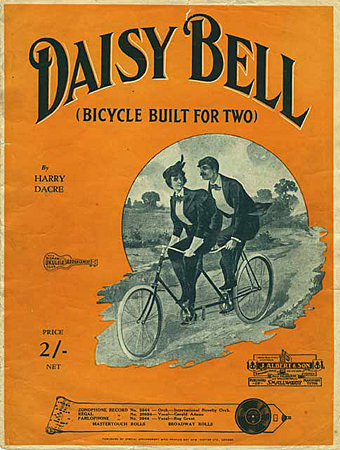

1: How to Construct a Time Machine, 1899

III: Description of the Machine

The Machine consists of an ebony frame, similar to the steel frame of a bicycle. The ebony members are assembled with soldered copper mountings.

The gyrostats’ three tori (or flywheels), in the three perpendicular planes of Euclidean space, are made of ebony cased in copper, mounted on rods of tightly rolled quartz ribbons (quartz ribbons are made in the same way as quartz wire), and set in quartz sockets.

Alfred Jarry testing a time machine, 1898

The circular frames or the semicircular forks of the gyro stats are made of nickel. Under the seat and a little forward are located the batteries for the electric motor. There is no iron in the Machine other than the soft iron of the electromagnets.

Motion is transmitted to the three flywheels by ratchet-boxes and chain-drives of quartz wire, engaged in three cogwheels, each of which lies on the same plane as its corresponding fly wheel. The chain-drives are connected to the motor and to each other through bevel gears and driveshafts. A triple brake controls all three shafts simultaneously…

Alfred Jarry

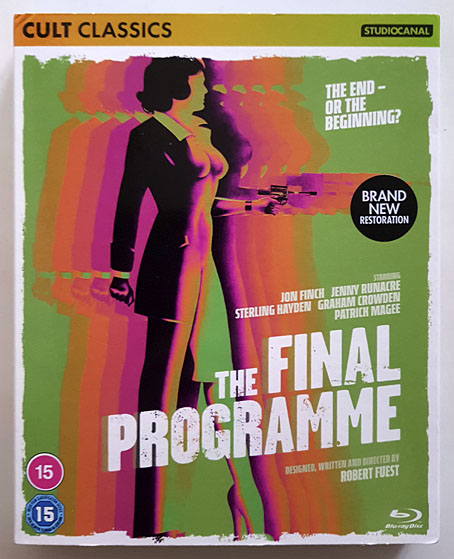

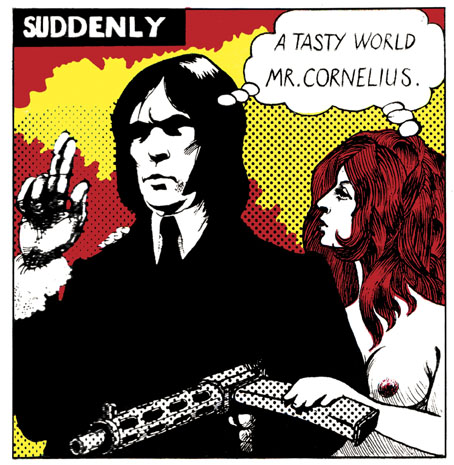

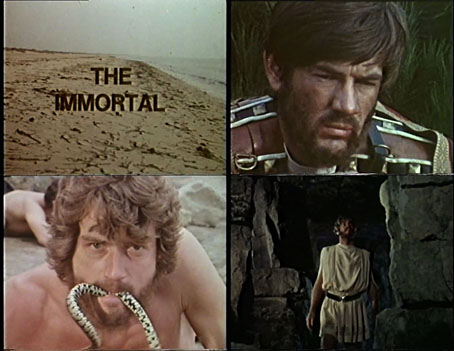

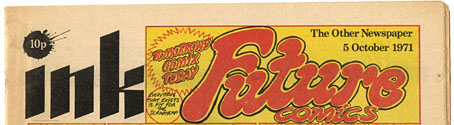

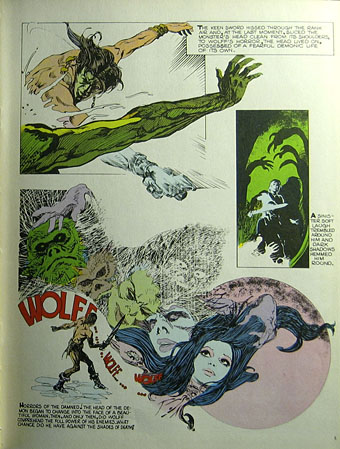

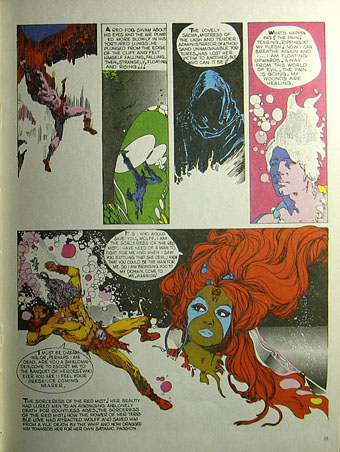

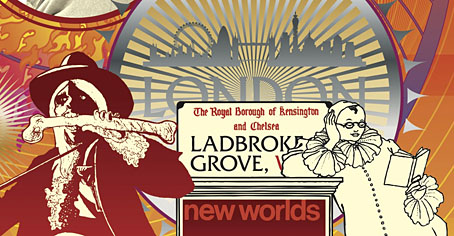

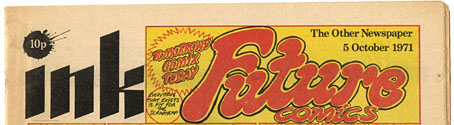

2: Dead Singers (aka All the Dead Singers), 1971

“That’s all in the past now.” Beesley waddled to the other the side of the tiled room and wheeled the black Royal Albert gent’s roadster across the clean floor. He paused to flip a switch on the wall. Belly Button Window flooded through the sound system. They were turning his own rituals against him. Now the devil had all the songs.

“All aboard, Mr C.” Reluctantly, Jerry mounted the bike. He was getting a bit too old for this sort of thing.

[…]

In London he slowed down, but by that time he’d blown it completely. Still, he’d got what Beesley wanted. Nothing stayed the same. Tiny snatches of music came from all sides, trying to take hold. Marie Lloyd. Harry Champion, George Formby, Noël Coward, Cole Porter, Billie Holliday, MJQ, Buddy Holly, The Beatles, Jimi Hendrix and Hawkwind. He hung on to Hawkwind, turning the car back and forth to try to home in, but then it was Gertrude Lawrence and then it was Tom Jones and then it was Cliff Richard and he knew he was absolutely lost. Buildings rose and fell like waves. Horses, trams and buses faded through each other. People grew and decayed. There were too many ghosts in the future. In Piccadilly Circus he brought the Mercedes to a bumping stop at the base of the Eros statue and, grabbing the Royal Albert, threw himself clear. He was screaming for help. They’d been fools to fuck about with Time again. Yet they’d known what they were getting him into.

Michael Moorcock, Ink Magazine

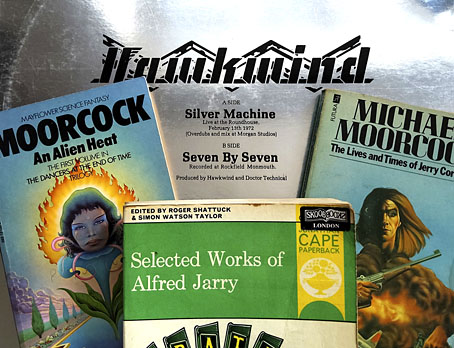

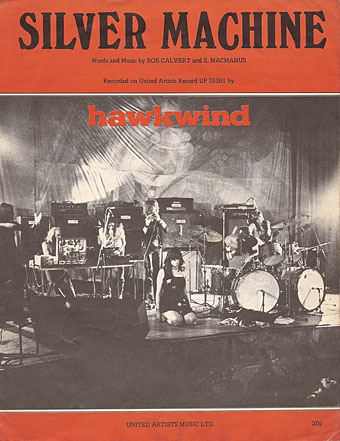

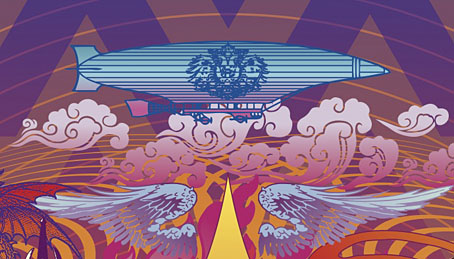

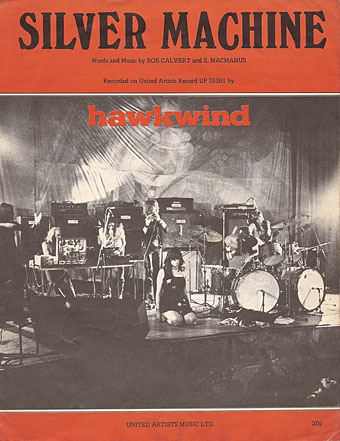

3: Silver Machine, 1972

Cover design by Tony Vesely with Pennie Smith (not the work of Barney Bubbles as stated elsewhere).

A dead singer.

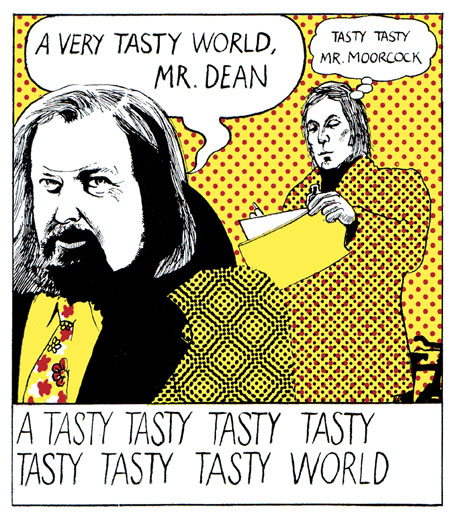

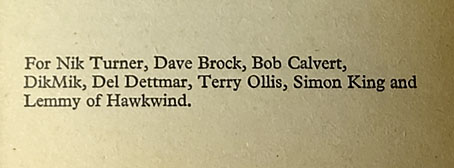

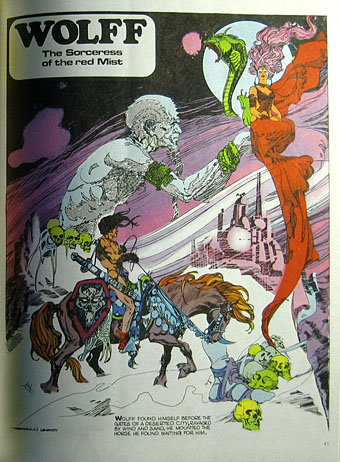

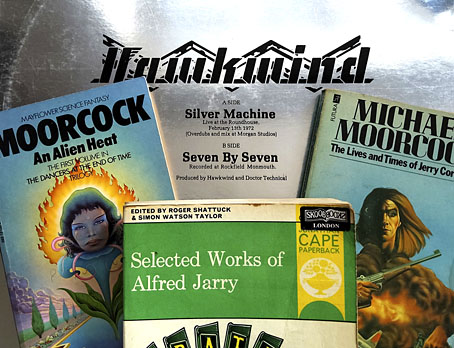

4: The Dancers at the End of Time, 1974

Dedication by Michael Moorcock in the 1974 Mayflower paperback of An Alien Heat—The First Volume in the Dancers at the End of Time Trilogy.

Outside the station they found themselves in the Strand and now Jherek saw something leaning against a wall on the corner of Villiers Street.

“Look!, Mrs Underwood—we are saved. A time machine!”

“That, Mr Carnelian, is a tandem bicycle.”

He already had his hands on it and was trying to straddle it as he had seen the others do.

“We would do better to hail a cab,” she said.

“Get aboard quickly. Can you see any controls?”

With a sigh, she took the remaining saddle, in the front. “We had best head for Regent Street. It is not far, happily. The other side of Piccadilly. At least this will prove to you, once and for all, that…”

Her voice was lost as they hurtled into the press of the traffic, weaving between trams and omnibuses, between horses and motor cars and causing both to come to sudden stops and stand stock still in the middle of the road, panting and shuddering.

Jherek, expecting to see the scene vanish at any moment, paid little attention to the confusion happening around them. He was having a great deal of trouble keeping his balance upon the time machine.

“It will be soon!” he cried into her ear, “it must be soon!” And he pedalled harder. All that happened was that the machine lurched onto the pavement, shot across Trafalgar Square at considerable speed, up the Haymarket, and was in Leicester Square almost before they had realized it. Here Jherek fell off the tandem, to the vast entertainment of a crowd of street urchins hanging about outside the doors of the Empire Theatre of Varieties.

“It doesn’t seem to work,” he said.

Michael Moorcock, The Hollow Lands—The Second Volume in the Dancers at the End of Time Trilogy

5: Machine music

6: “’Pataphysics is the science”, 1981

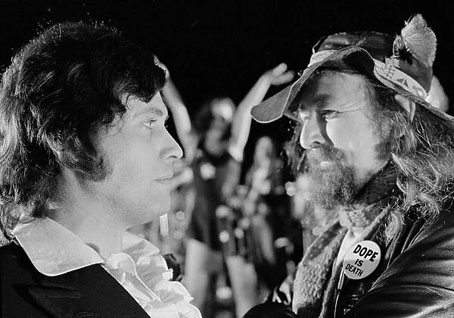

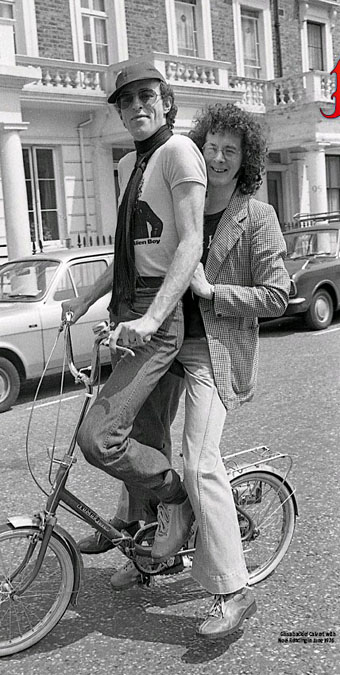

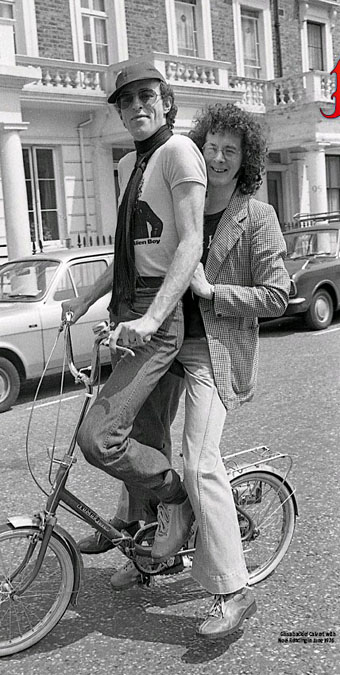

Robert Calvert and Noel Redding testing a time machine, 1976.

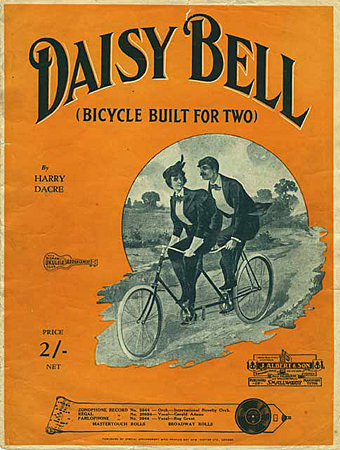

I read this essay by Alfred Jarry called, “How to Construct a Time Machine”, and I noticed something which I don’t think anyone else has thought of because I’ve never seen any criticism of the piece to suggest this. I seemed to suss out immediately that what he was describing was his bicycle. He did have that turn of mind. He was the kind of bloke who’d think it was a good joke to write this very informed sounding piece, full of really good physics (and it has got some proper physics in it), describing how to build a time machine, which is actually about how to build a bicycle, buried under this smoke-screen of physics that sounds authentic.

Jarry got into doing this thing called “’Pataphysics”, which is a sort of French joke science. A lot of notable French intellectuals formed an academy around the basic idea of coming up with theories to explain the exceptions to the Laws of the Universe, people like Ionesco the playwright.

The College of metaphysics. I thought it was a great idea for a song. At that time there were a lot of songs about space travel, and it was the time when NASA was actually, really doing it. They’d put a man on the moon and were planning to put parking lots and hamburger stalls and everything up there. I thought that it was about time to come up with a song that actually sent this all up, which was Silver Machine.

Silver Machine was just to say, I’ve got a silver bicycle, and nobody got it. I didn’t think they would. I thought that what they would think we were singing about some sort of cosmic space travel machine. I did actually have a silver racing bike when I was a boy. I’ve got one now, in fact.

Robert Calvert, Cheesecake fanzine no. 5

• Related: Marcus O’Dair on ’Pataphysics: Your Favourite Cult Artist’s Favourite Pseudoscience.

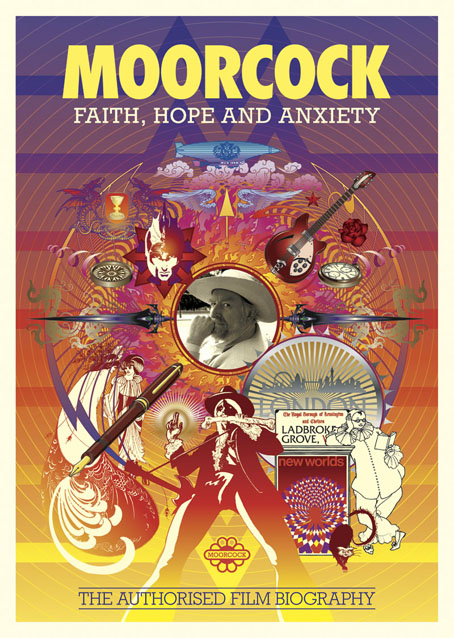

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Notes from the Underground

• Hawkwind: Days of the Underground

• The Chronicle of the Cursed Sleeve

• Rock shirts

• The Cosmic Grill

• Void City

• Hawk things

• The Sonic Assassins

• New things for July

• Barney Bubbles: artist and designer