The pulp fiction of the early 20th century favoured remote or uncharted islands as locations for the bizarre and the fantastic; in isolated jungles all manner of savage and grotesque behaviour could take place out of sight of the civilised world. Islands are secure from interference; they can be visited by accident or intention, and later fled from when everything goes wrong. The Island of Doctor Moreau is an early example of the type although Jules Verne’s The Mysterious Island (1874) pre-dates it by twenty-two years. The Island of Lost Souls (1932), the first film adaptation of the Wells novel, is one of a crop of mysterious islands that appeared in the 1930s following the success of the Universal adaptations of Dracula (1931) and Frankenstein (1931). The recent Eureka DVD/Blu-ray edition of the film is the first UK release to present the film in its original, uncensored form. I watched it this weekend.

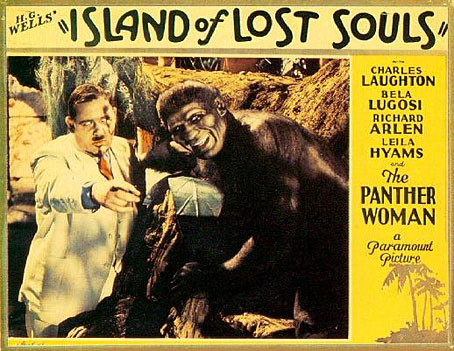

Moreau (Charles Laughton) and Montgomery (Arthur Hohl) at work.

HG Wells famously hated the film, and his vociferous complaints helped to ensure it was banned in Britain until 1958. Even without Wells’ complaints there was enough there to bait the censors who declared it to be “against nature”: writers Philip Wylie and Waldemar Young push the erotic implications of Wells’ story to a degree that would have been impossible in 1896, and would be equally impossible two years later when the Hays Code clamped down on cinematic salaciousness. Charles Laughton’s Moreau is eager to discover whether Lota, the Panther Woman (Kathleen Burke), will show any sexual interest in the marooned Edward Parker (Richard Arlen). The bestiality theme continues when Parker’s fiancée arrives on the island and finds one of Moreau’s Beast People at her bedroom window. Add to this Moreau’s declaration that he feels like God (a similar line was cut from James Whale’s Frankenstein), a traditional British squeamishness towards maltreating animals (unless they’re foxes), and the Panther Woman’s skimpy outfit, and it’s no surprise that the authorities collapsed with the vapours.

Sensationalism aside, this is one of the greatest horror films of the early 1930s, and one which follows its source material with much more fidelity than Universal’s Dracula and Frankenstein. The production had been commissioned by Paramount to capitalise on the success of the Universal films, hence the presence of a very hirsute Bela Lugosi as the Sayer of the Law. Cinematographer Karl Struss had worked the year before on Rouben Mamoulian’s excellent Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde; prior to this he photographed Sunrise (1927) for Friedrich Murnau. The combination of Struss’s chiaroscuro compositions, some adept direction from Erle C. Kenton (including crane shots), and a tremendous performance by Charles Laughton puts The Island of Lost Souls in a different league entirely to Tod Browning’s stagey and over-rated Dracula. Laughton’s cherub-faced Mephistopheles is a performance that runs counter to the cod theatricals of the period: he’s sly, confident and completely authoritative even if he looks nothing like Wells’ white-haired doctor.