“What is especially needed is great sensitivity: to look upon everything in the world as enigma….To live in the world as in an immense museum of strange things.” —Giorgio de Chirico

A few weeks ago I made a list of feature films that might be regarded as having the characteristics of a Thomas Pynchon novel without being based on any of Pynchon’s books. The post prompted several suggestions for other candidates, including recommendations to watch Jim Gavin’s TV series, Lodge 49, an American production that ran for two seasons from 2018 to 2019 before being cancelled due to low ratings. Having now watched the series I can say that I enjoyed it very much, and it is very Pynchonian, unsurprisingly when it not only gestures to the title of Pynchon’s second novel, The Crying of Lot 49, but also borrows from its storyline.

Ernie (Brent Jennings) has just been contemplating a print from the Ars Magna Lucis (1665) by Athanasius Kircher. Near the end of the second series he leaps through an image from the same book.

Lodge 49 presents a unique mélange of alchemy, surfing, secret societies, aerospace engineering, pool cleaning and cryptocurrency, with the added bonus of songs by the much-missed Broadcast being woven into the narrative. The series is consistently funny, humour being another essential Pynchonian ingredient, while the episodes are littered with references to (or correspondences with) Pynchon’s oeuvre: two of the main characters are an ex-surfer and an ex-sailor; the defunct aerospace company, Orbis, is modelled on Pynchon’s Yoyodyne from V. and Lot 49; there’s a trip to Mexico, a visit to an auction, and mention of a Remedios Varo exhibition (Lot 49 again); there are even references to Antarctic mysteries (V.), the Hollow Earth (Mason and Dixon) and the V-2 rocket (Gravity’s Rainbow). And those are only a few of the things I happened to catch as a first-time viewer. This is unusual territory for a small-scale television series, even if American TV has loosened up in recent years to allow a more eclectic range of material.

Larry (Kenneth Welsh) in the Sanctum Sanctorum with a plate from the Splendor Solis on the wall.

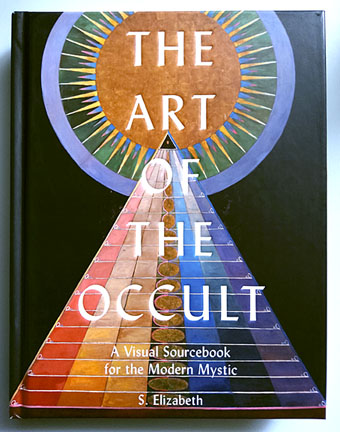

The Lodge 49 of the title is part of a global network of lodges that form the Ancient & Benevolent Order of the Lynx, a cross between a Masonic order and an occult cabal, founded by one Harwood Fritz Merrill, a Scottish alchemist, writer and explorer. (Merrill’s biography and the history of the Order of the Lynx is detailed here [PDF].) Alchemy is a persistent theme in the series but remains in the background for the most part, literally so inside Lodge 49 (Long Beach, California) and Lodge 1 (London) where the walls are decorated with prints of alchemical engravings. It would have been tempting to identify all of these pictures but most of them can be found in Taschen’s excellent Alchemy and Mysticism picture book so it’s easier to direct the curious to the Taschen volume. The prints also seemed to be there more to provide suitable set decoration rather than be significant in themselves, with one notable exception (see below).

Connie (Linda Edmond) going deeper into the mysteries of Lodge 1. The print is from Cabala, Spiegel der Kunst und Natur: in Alchymia (1615) by Stephan Michelspacher.

More intriguing was the appearance of several paintings which did seem significant although they might equally have been there to generate audience speculation. Film and TV drama is made today in the full awareness that every detail is liable to be screen-grabbed and scrutinised by obsessive viewers, a situation that offers the potential for directors and designers to incorporate details that may have no special significance but are simply there to fuel online chatter. It’s difficult to tell if this is what Gavin and co. were doing, especially when the prematurely truncated series contains so many loose ends and unexplained moments. But paranoia is in part the search for a significance that may not exist outside the mind of the paranoiac so a small degree of concern about being gamed by the creators of Lodge 49 seems warranted here, as well as adding to the general Pynchon factor. Despite all the Pynchoniana mentioned above the series is light on the paranoia that’s a constant in Pynchon’s novels so why not cultivate a little paranoia in the audience itself?