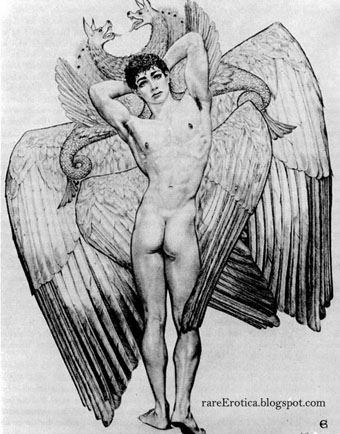

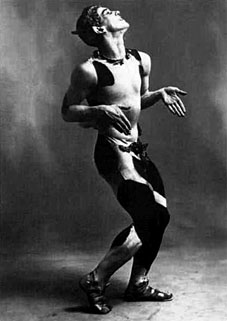

More obscure art, only now we’re talking really obscure. This remarkable picture, The Hermaphrodite-Angel of Peladan by Czanara, turned up in the archives of Russ Kick’s seemingly abandoned Rare Erotica blog. “Czanara” was one Raymond Carrance (1921–?), a gay artist who I haven’t come across before and who seems to be completely absent not only from my library, but from most of the web. A great shame, if there’s more of his work like this I want to see it.

The “Peladan” of the title might be a reference to Sâr Péladan, founder of the Catholic Order of the Rose and the Cross in fin de siècle Paris, and guru to a number of significant Symbolist painters, including the brilliant Jean Delville. Hermaphroditism and androgyny were important themes for Péladan who declared, in an outburst typical of the period, “the androgyne, is the plastic ideal!” Czanara’s picture is certainly Symbolist in its details—those multiplied wings and hippogriffs—even if its intent is most likely a result of mundane pornographic imperatives.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

• The fantastic art archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Angels 4: Fallen angels

I have an abiding fascination with the

I have an abiding fascination with the