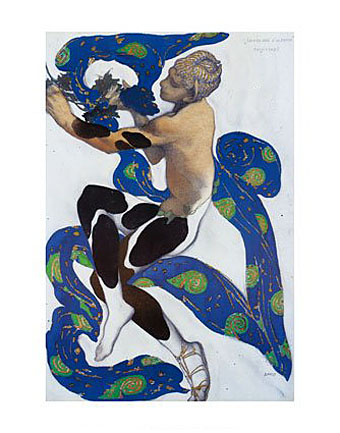

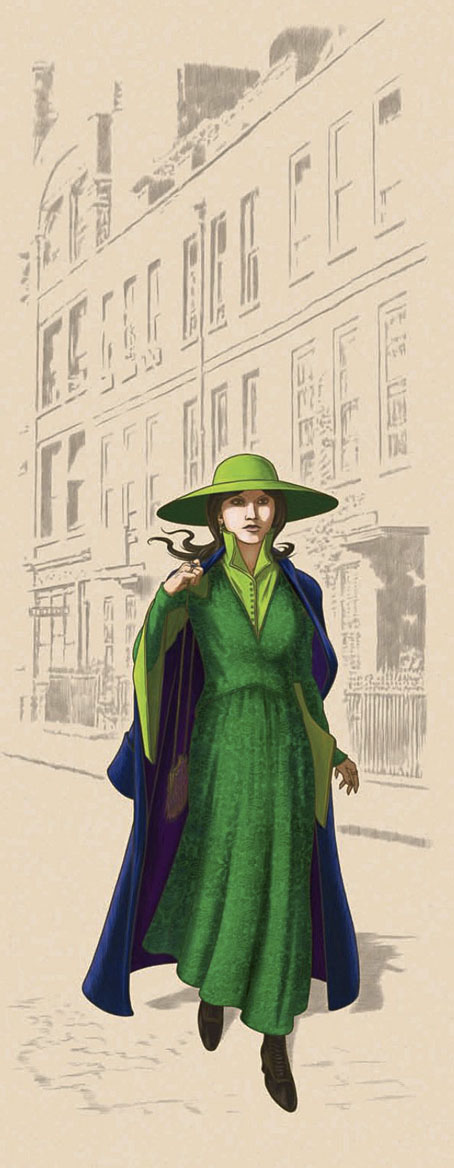

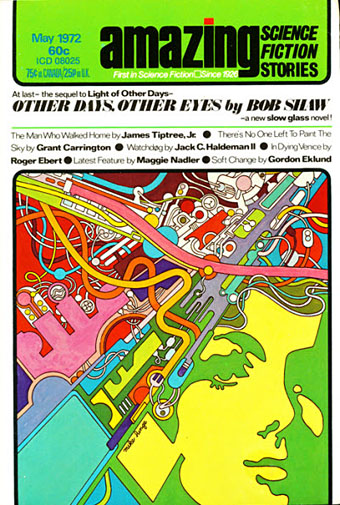

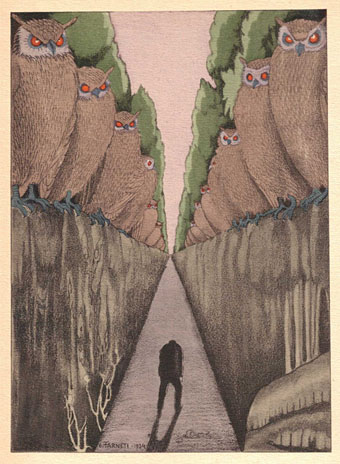

Adeline Carr, aka “The Soul”, wandering through the streets of Holborn while worrying about her future. Her dress is an Erté creation with curiously complicated sleeves.

After checking out of my Bloomsbury hotel on Saturday morning I decided to walk over to the nearby Atlantis Bookshop, London’s oldest occult bookseller, which is located in Museum Street close to the British Museum. I know the shop well but this visit was different since the route would take me past a number of locations mentioned in the fiction serial which runs throughout the Moon and Serpent Bumper Book of Magic.

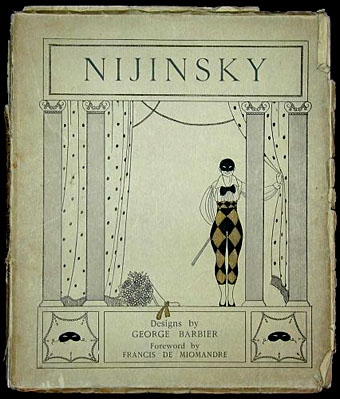

The Dweller in the Abyss is a story about “The Soul”, a young woman in the 1920s who was originally going to be a kind of occult investigator for a comic series Alan Moore and I were planning for ABC in the late 1990s. This didn’t work out for a variety of reasons but The Soul has been reborn in the new book, with her character reinvented in order to demonstrate the personal evolution of a neophyte entering the world of magic. Adeline Carr, “The Soul”, is an artist’s model who lives in the first-floor flat above the Atlantis shop. I won’t go into detail about the story, the whole thing needs to be read with the complementary material surrounding it, but Adeline’s wanderings around this quarter of the city take her to a number of well-known locations which you can visit today, and which I illustrated to a greater or lesser degree.

1: Russell Square

The first location I encountered—although my drawing of it appears near the end of the story—is the park in Russell Square, one of two such parks in the Bloomsbury area. It was raining on the morning I was there but Adeline’s walk through the park takes place on a sunny spring afternoon. The real place is rather more wooded than I showed it (there are more trees on the page which faces this one) but artistic licence is in operation here, and the park has been reorganised once or twice since the 1920s.

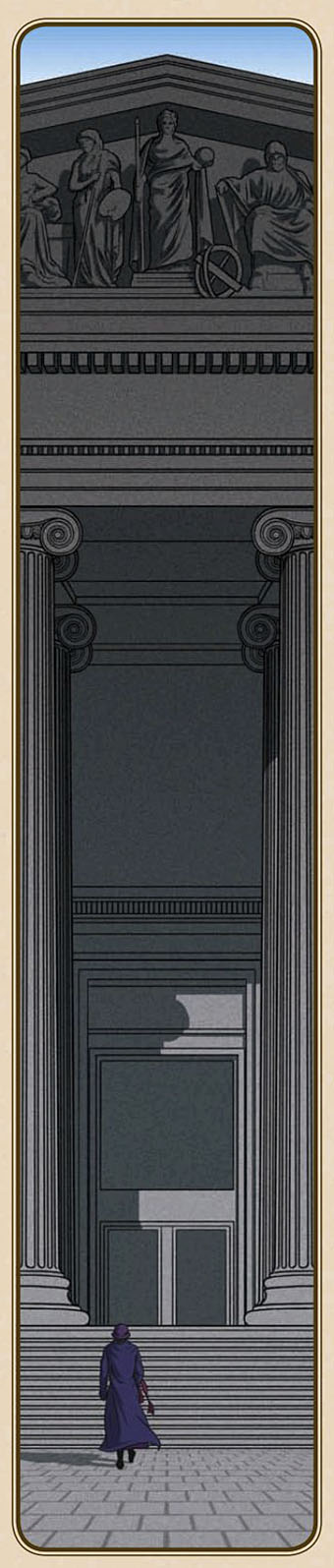

2: The British Museum

The next location is one I didn’t photograph, the British Museum. If it hadn’t been raining I might have walked through the gates to get a corresponding shot of the portico but the rain was heavier at this point and a large mass of umbrella-wielding tourists were crowding the entrance.

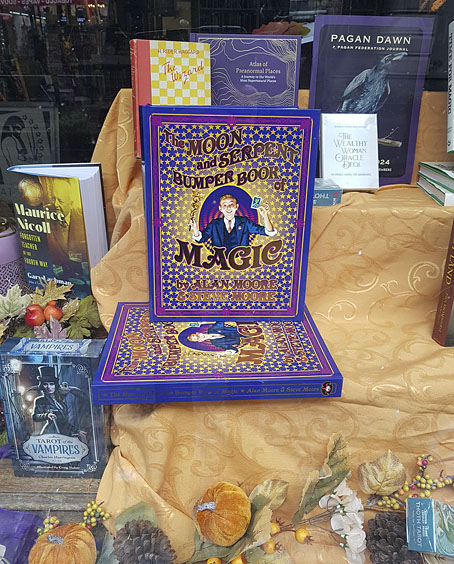

3: Museum Street

Into Museum Street and the Atlantis shop where the Bumper Book of Magic is visible in the window! This view shows the windows above the shop where Adeline lives. (Adeline’s windows aren’t a precise match but artistic licence again… Also, windows get replaced, especially after the wartime bombing that London endured.) The shop hadn’t opened yet so I walked round the corner into Bloomsbury Way to face the imposing bulk of Nicholas Hawksmoor’s church.

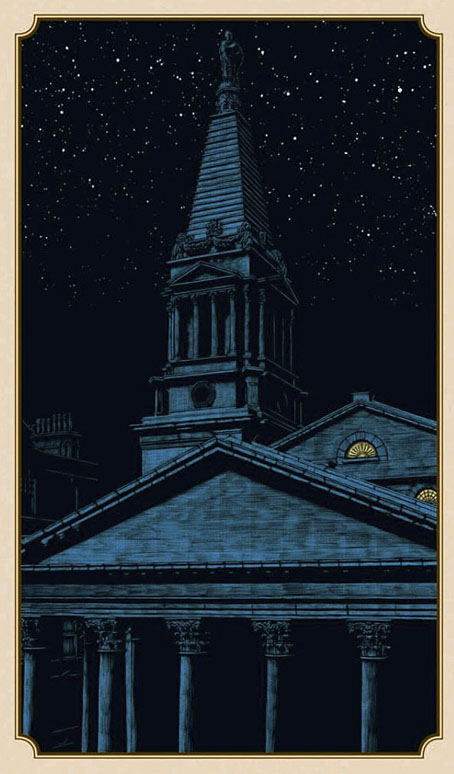

4: St George’s, Bloomsbury

To date, this building and Christ Church, Spitalfields, are the only Hawksmoor churches I’ve visited in person. The church is an important location in Adeline Carr’s journey into magic, being the place where her spiritual revelations begin and reach their eventual climax. The pyramid-capped tower looks slightly different to the one I was drawing. The steeple, which is based on Pliny’s description of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, was originally decorated at its base with statues of lions and unicorns but these were removed during a restoration of the building in the 1870s. Like many London buildings, the church suffered from the ravages of neglect, wartime bombing and air pollution during the 20th century (Hawksmoor’s St John, Horsleydown, was destroyed entirely during the Blitz). Restoration of St George’s began in the late 1990s, a process which included the return to the steeple of the missing lions and unicorns. (See this website.) Visiting the place this time I was hoping to get a view of the tower from the passage that runs along the side but the gate to this was locked. You can, however, see the church from the rear via a narrow road where the steeple rises over the dingy back rooms which fill out the plot.

5: The Atlantis Bookshop

And so to the Atlantis shop again. It was a genuinely magical moment seeing the book in the window after spending so much time thinking about this very location and the events that take place in the flat above. By coincidence (or is it? etc), the book sitting next to it is by Gary Lachman who I’d been with the previous evening for the book launch. After the shop had opened I talked for a while with the proprietors, showing them the place on page 39 of the Bumper Book where their establishment is mentioned. The Atlantis isn’t the only occult bookshop in London (or even the only one in Bloomsbury…Treadwell’s is nearby) but if you’re in London it should be your first port of call if you’re looking for a copy of the Bumper Book.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Moon and Serpent Rising

• Serious houses: The Lud Heat Tapes, 1979

• London churches of the XVIIth and XVIIIth centuries

• The Cardinal and the Corpse

• Terror and Magnificence

I have an abiding fascination with the

I have an abiding fascination with the