Flannery O’Connor with one of her many peacocks.

When the peacock has presented his back, the spectator will usually begin to walk around him to get a front view; but the peacock will continue to turn so that no front view is possible. The thing to do then is to stand still and wait until it pleases him to turn. When it suits him, the peacock will face you. Then you will see in a green-bronze arch around him a galaxy of gazing haloed suns. This is the moment when most people are silent.

Flannery O’Connor

Essay of the week was without a doubt Living with a Peacock by the great Flannery O’Connor, originally published in Holiday magazine in September 1961. I’d heard about Flannery’s peacocks before but had no idea she was such a pavonomane. Thanks to Jay for the tip!

• “‘He’s chameleon, comedian, Corinthian and caricature.’ But he was more like the very hungry caterpillar, munching his way through every musical influence he came across…” Thomas Jones reviews two new books about David Bowie for the LRB.

• In June Mute Records release The Lost Tapes by Can, a 3-CD collection. Here’s hoping this doesn’t merely repeat the outtakes that’ve been circulating for years as the Canobits bootlegs. This extract is certainly new.

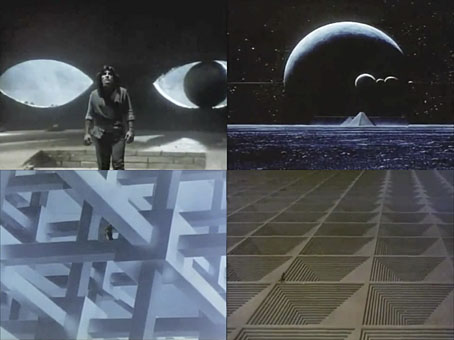

• Animator Suzan Pitt, director of the remarkable Asparagus (1979), discusses her new film, Visitation, inspired, she says, by reading HP Lovecraft in a cabin while wolves howled outside.

• Night Thoughts: The Surreal Life of the Poet David Gascoyne, a biography by Robert Fraser reviewed by Iain Sinclair.

The Dangerous Desire (1936) by Richard Oelze (1900–1980) at But Does It Float.

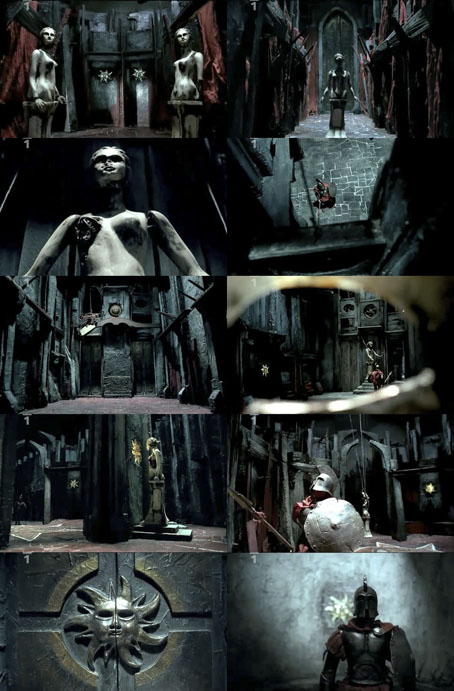

• Making the Mari: the stuff of nightmares brought into the world by Jefferson Brassfield.

• The Background to the Moorcock Multiverse: Karin L. Kross reviews London Peculiar.

• Orson Welles’s lost Heart of Darkness screenplay performed for the first time.

• The Erotic Films of Peter de Rome: the new BFI DVD collection reviewed.

• Page designs by Alphonse Mucha for Ilsée, Princess de Tripoli (1897).

• A Slow-Books Manifesto by Maura Kelly.

• Tim Parks asks “Do we need stories?”.

• Musical table by Kyouei Design.

• Horror Asparagus Stories (1966) by The Driving Stupid | Peacock Lady (1971) by Shelagh McDonald | Peacock Tail (2005) by Boards of Canada.