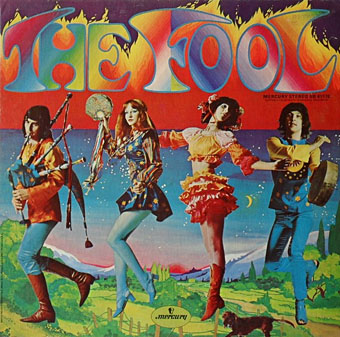

The Fool (1968).

Many people know the work of design collective The Fool even if they couldn’t tell you the name or the names of any of the individuals involved. The accelerated career trajectory of Dutch artists Marijke Koger and Simon Posthuma took them from a hippie enclave on the isle of Ibiza in 1966, to London and work for The Beatles throughout 1967 thanks to their distinctive brand of rainbow-hued psychedelia. Marijke Koger says the name The Fool was chosen after they met Crowley-obsessed blues singer Graham Bond who introduced them to the Tarot deck. Barry Finch and Josje Leeger later joined Koger and Posthuma. For The Beatles the group created the short-lived mural for the Apple boutique in Baker Street (removed after complaints), the decoration on John Lennon’s piano, and the inner sleeve for the Sgt Pepper album. The gatefold interior of the album was going to incorporate a Fool painting but Robert Fraser apparently persuaded the band to replace this with a group photo. The Fool themselves (and their decor) appear in the Beatles-produced feature film, Wonderwall (1968).

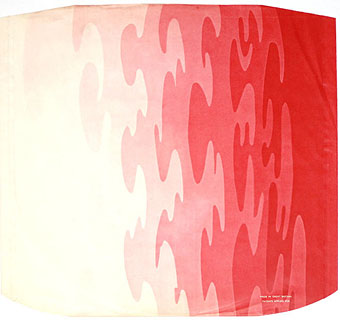

Proposed interior for the Sgt Pepper album (1967).

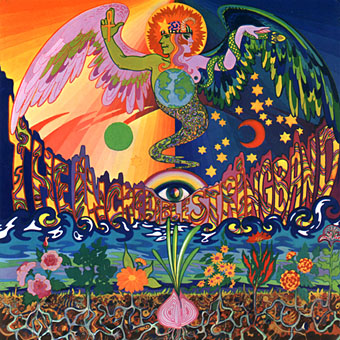

Given all this sudden visibility it’s surprising they weren’t more in demand for album cover designs although they were also busy producing florid outfits for other groups. The Beatles clothes on the All You Need is Love broadcast are Fool creations. Of the album covers, the one for The Incredible String Band is probably the most well-known. This small collection reminds me I still haven’t heard Evolution by The Hollies. The work on that cover led to a collaboration with Graham Nash on an album by The Fool (and session musicians) in 1968. The collective split up in 1969 with Marijke Koger and Simon Posthuma relocating to California.

• Marijke Koger-Dunham’s site

• Simon Posthuma’s site

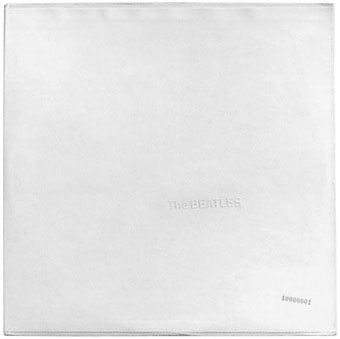

Sgt Pepper inner sleeve.

The 5000 Spirits Or The Layers Of The Onion (1967) by The Incredible String Band.

Evolution (1967) by The Hollies. Clothes and design by The Fool, photo by Karl Ferris.

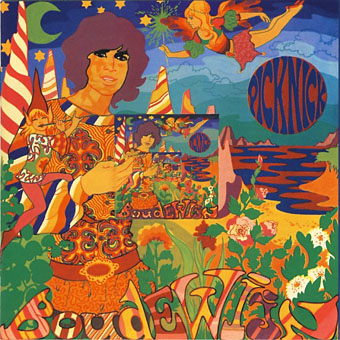

Picknick (1967) by Boudewijn De Groot.

Move (1968) by The Move.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The album covers archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Through the Wonderwall