Waiting by Liz Brizzi.

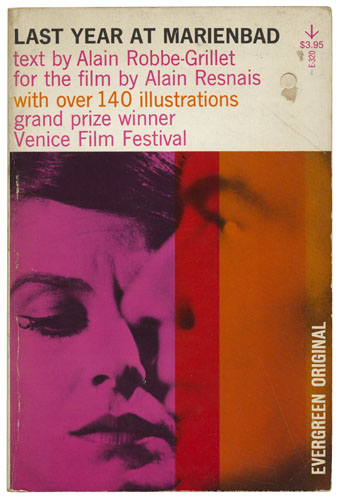

• “Music, politics, sex, and art were also widely represented by Evergreen. Gerald Ford famously maligned the magazine on the floor of Congress for printing the likeness of Richard Nixon next to a nude photo.” Jonathon Sturgeon on the return of an avant-garde institution.

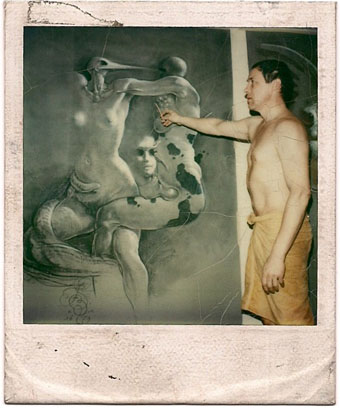

• “The hallucinogenic properties of language are widely recognized by all repressive societies…which treat words like other tightly controlled substances.” Askold Melnyczuk reviews Where the Bird Sings Best, a novel by Alejandro Jodorowsky.

• Mixes of the week: A Mix For Thomas Carnacki by Jon Brooks whose Music for Thomas Carnacki has been reissued on vinyl; Solid Steel Radio Show 27/3/2015 by DJ Food.

One of the few vice-friendly cities left in the US, New Orleans remains his spiritual home, or whatever the atheist equivalent is. Waters’ supposed favourite bar in the world is here in the historic French Quarter. The Corner Pocket is a gay dive bar with tattooed strippers—filthy in exactly the way Waters likes.

“Trash and camp just don’t cut it any more,” he told a rapt audience at his interview panel on Friday. “Filth still has a punch to it. The right kind of people understand it and it frightens away the timid.”

John Waters growing older disgracefully

• Songs of a Dead Dreamer and Grimscribe by Thomas Ligotti are being republished in a single edition by Penguin. Jeff VanderMeer wrote the foreword.

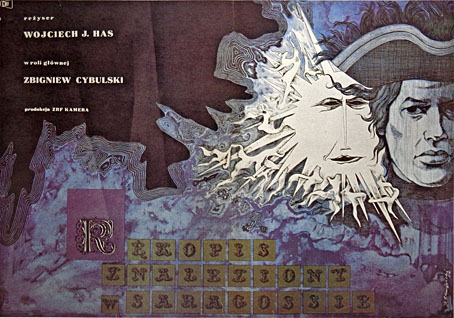

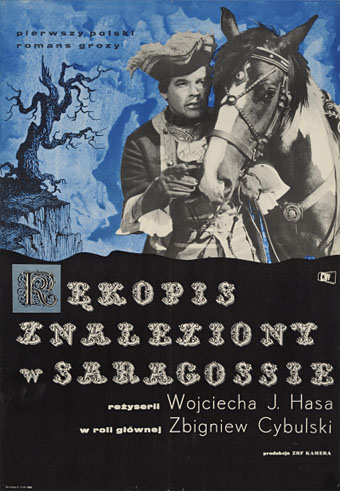

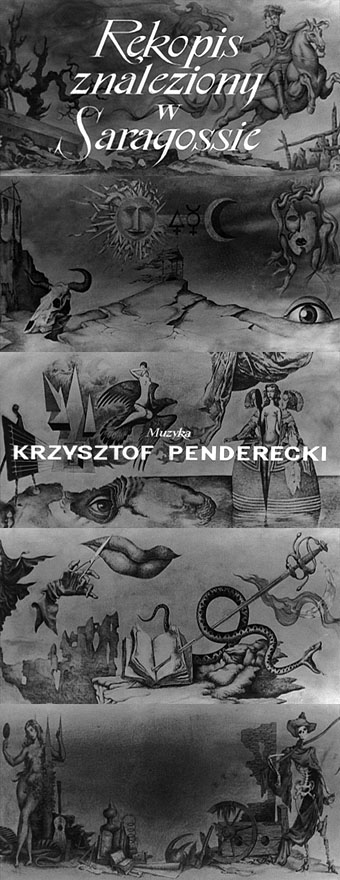

• “The film is brimming with Bacchanalian revelry, arcane mystery and mortal dread.” Robert Bright on The Saragossa Manuscript by Wojciech Has.

• Alistair Livingston has posted page scans from When Darkness Dawns, volume two of his zine from the early 80s, The Encyclopedia of Ecstasy.

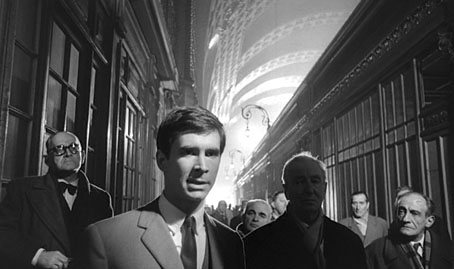

• “Without first understanding the flâneur we cannot understand the development of arcades,” says Aaron Coté.

• At A Journey Round My Skull: Jo Daemen cover designs; at 50 Watts: the art of Manuel Bujados.

• Vast spacecraft and megastructures: Jeff Love on the science-fiction art of Chris Foss.

• At Dangerous Minds: RE/Search’s Vale on JG Ballard and William Burroughs.

• RIP John Renbourn

• Pentangling (1968) by Pentangle | Lyke-Wake Dirge (1969) by Pentangle | Lord Franklin (1970) by Pentangle